A Catholic Remembers Bloody Sunday 1965

60 Years After Selma, Can Catholics Help to Renew American Democracy?

March 7th marked the 60th anniversary of the so called “Bloody Sunday” of 1965, when Alabama State Troopers and local police brutally attacked civil rights marchers with batons, police dogs, and tear gas at the now infamous Edmund Pettus bridge in Selma. Much was published Sunday in the secular media regarding this anniversary, but I didn’t see any mention of it in Catholic venues.

[AP File Photo. Selma, Alabama at Pettus Bridge]

We Catholics should also remember Bloody Sunday, especially as an occasion to reflect upon the example of those American Catholics who were an integral part of the civil rights movement, which made significant progress in overcoming the Jim Crow era of racial segregation. In so doing, they also helped the country towards the realization of the founding ideal of American democracy, that all were created equal and endowed with human rights, including the right to self-government.

Sadly, I am not able to say that the majority of Catholics participated in, or even supported, the civil right movement, as we came along only slowly. Rather, my point is that those who did should be recognized as exemplars of living out the Gospel in a way that not only conforms to the fundamental biblical injunction to care especially for the marginalized. It also aligns with the discernment of the magisterium in the modern era, as would be further articulated by the Second Vatican Council, and in the many documents on social ethics promulgated by the Church since then.

Among those examples, I will highlight Catholics associated with the Good Samaritan Hospital in Selma, Alabama.

The Good Samaritan Hospital in Selma, Alabama

This hospital was part of the Edmundite Southern Missions under the Society of St. Edmund, which continues to this day, although they no longer operate the hospital. The Good Samaritan Hospital was a collaboration with the Sisters of Saint Joseph to provide medical care to an impoverished and marginalized community of African Americans in the Jim Crow South.

According to a story by Robert Howell, published online by CNN in 2010, “The Society of Saint Edmund had come to Selma in 1937 to set up its mission. …The Edmundites faced intimidation from local officials and constant death threats from the white community as well as the Ku Klux Klan.” The story highlights the Edmundite Fr. Maurice Ouellet, who joined the society in 1952. “By 1965, Ouellet found it harder and harder to separate his duties as a clergyman from his sympathy for the plight of his parishioners. He was one of few white men who attended the meetings organized by [Reverend Martin Luther] King’s supporters in Selma.” In Ouellet’s initial conversations with King, the latter was delighted that some white Catholics were coming to express support for the movement, whereas the former was frustrated they were so few and so late.

[Fr. Maurice Ouellet, SSE]

Ouellet not only faced intimidation and threats from the segregationists, but found himself at odds with Church leaders. In 1963, the Archbishop of Mobile-Birmingham T.J. Toolen had written the following to him.

“I won’t stand for any priest of the Diocese going in parades or sit-ins. ... The march on Washington and the marches in Baltimore have done absolutely no good. ... Of course, you realize you are stirring up great trouble for yourself, as I have told you, Selma and the surrounding country as far as the negro is concerned is and always has been the worst in the state. They hate the negro, and hate him worse than they love the Church. ... While I am Bishop of Mobile, there will be no picketing by priests or nuns, and no marching.”

Having been barred from participating, Ouellet and the other Edmundites were not among the demonstrators on Bloody Sunday on March 7, 1965. They “found themselves on the front lines,” however, when the sirens started sounding after mass as “Selma law enforcement and Alabama State Police, led by Sheriff Jim Clark, … forced back nearly 600 marchers with tear gas and billy clubs.” Because Good Samaritan was the only hospital in Selma that would treat black patients, the over 100 injured were all taken there. Inside the hospital, Fr. Ouellet encountered the African American nurse Etta Perkins, who was “tending to the wounded.” He told CNN’s Howell that he recalled her “hollering” amidst the turmoil: “Father, they’re going to kill us all.” Her concern was well-founded, moreover, as “[t]he civil rights activist Jimmie Lee Jackson had died there two and a half weeks before.”

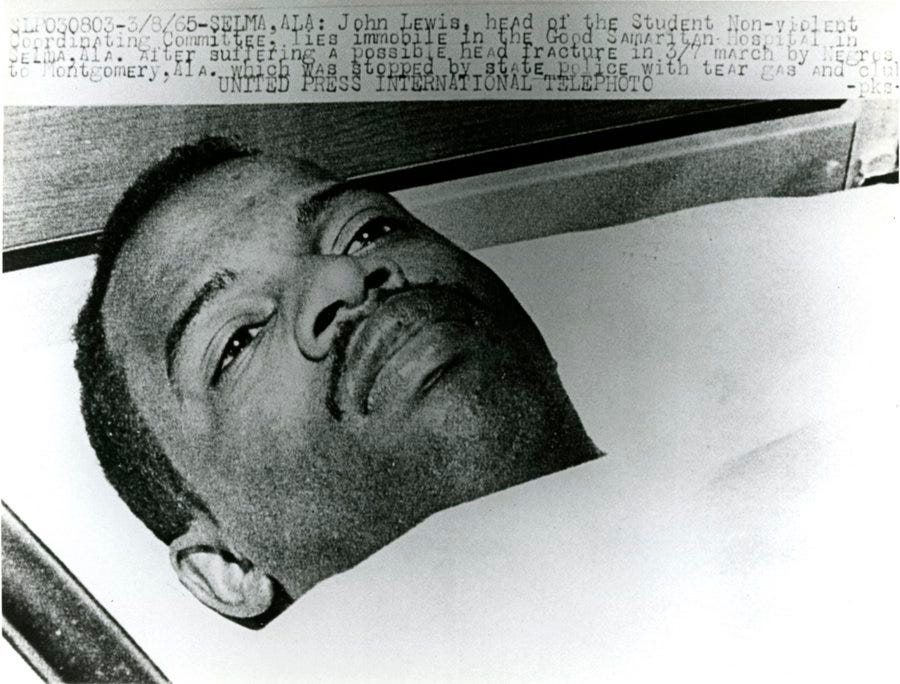

Because white physicians in the area refused to work in a “black hospital,” much of the care was provided by the Sisters. The most prominent of the patients that day was the young civil rights icon John Lewis, a devout Christian who was then head of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee. Besides serving as a leader of the Civil Rights Movement for decades, Lewis was elected to congress in 1986 and served until passing on to his reward in July of 2020. The famous picture of him lying in his hospital bed with a fractured skull and concussion is found below.

[United Press International photo, taken from John Lewis’s X account]

Lewis was assisted at the bridge by Fr. Ouellet and taken to the hospital. While there, he was cared for by the Sisters of St. Joseph, including Sr. Barbara Lum, pictured below in a contemporaneous photo with a young boy.

[Archives of Sisters of St. Joseph]

According to a story by New England Public Media, Sr. Lum said “I remember coming out into the hall for some reason... and people identified him. ‘That’s John Lewis, lying on the stretcher, waiting to be taken up and admitted into the hospital.’ And he still had his raincoat on, and he was just lying there totally quiet, probably unconscious.” Fr. Ouellet saw it a bit differently. He told Howell:

Lewis “didn’t say anything,” Ouellet recalls. “I couldn’t really tell if he was conscious. His eyes were vague, but that was his way, I understand. He had been beaten so many times that when he did get beaten, he would just go quiet. That is when he would go into his mode of nonviolence.”

Later, Sr. Lum recalls Lewis asking her “Sister, don’t you think this is a high price to pay for freedom?”

[Lewis and Sr. Lum in 2014 at the Rochester Educational Opportunity Center]

Five decades later, Lewis addressed the graduates of the Rochester Educational Opportunity Center, where Sister Barbara was a faculty member.

Overcome with emotion, he said, “Thank you to Sister Barbara and all the SSJs — thank you for what you did on March 7, 1965, and before and after... I was wounded, hit in the head and thought I was going to die. I thought to myself, How can President Johnson send more troops to Vietnam, but not send troops to Selma to protect us? You took care of a lot of people that day and I have been wanting to come here for a long time and say thank you.”

After Bloody Sunday, additional religious and clergy gathered in Selma in preparation for a march to Montgomery. According to a webpage I can’t relocate, the photo below includes not only the Sisters of St. Joseph, but Edmundite seminarians.

Needless to say, Archbishop Toolen was not pleased, writing:

"I want Ouellet out of Selma. He is a good priest but crazy on this subject. ... It is destroying the Church in Alabama and I cannot sit idly by and see this done. ... No one has done more for the negro people than I have but that is all forgotten by these new men who have come in and only see one side of a question. I have put up with as much as I am going to. ... I have always felt closer to the Edmundite Fathers than any other Community in the Diocese, but Selma has cured this.

- Archbishop T.J. Toolen, March 18, 1965

According to Howell, “The marchers finally left Selma for Montgomery on March 21, two weeks after Bloody Sunday. Many of the supporters who joined the march that day were clergy from across the nation.” This was a crucial development in which numbers of Catholic religious and clergy joined publically in solidarity with a broad coalition of those taking a stand for the civil rights of African Americans.

Howell continues:

But Ouellet was not one of them. Toolen had ordered him to leave Selma. It was a difficult time for the young reverend, who had poured so much of himself into the causes of the black community. “I cried. It was the only way I could handle it at the time.”

…

[Fr. Ouellet at the playground, 1963]

Continuing the citation from Howell:

Ouellet says the bishop was well aware of the turbulent times and the danger they all faced. He admits that being moved out of Selma may have saved his life. “I was really committed. It was not that I wanted to get myself killed; it was just, if this is what it takes, then this is what it takes.”

After continuing his career with the Edmundites for nearly 30 years in cities across the country, Ouellet is retired and back in Selma, where the Edmundites continue their mission work. In addition to feeding and clothing the poor, they operate rural clinics and in many cases still provide the only doctors available to their patients.

Ouellet lives in a home for the elderly. There, he is cared for by African-American nurses, many of them from the families he once served.

At the time this story was written in 2010, the United States had its first African American president and it seemed that the United States had taken a decisive step to finally overcome the legacy of slavery and realize the promise of a multiracial democracy. Today, however, a new era is unfolding in which many of the gains of the Civil Rights era are being rolled back, and many other pillars of American democracy are being threatened. Indeed, even fundamental rights such as that of free speech are under threat.

One would hope that committed Catholics will recognize these new threats and come to the forefront of the struggle to defend the dignity of the human person and build a society marked by social friendship. This would certainly follow from the the “integral and solidary humanism” of Catholic Social Doctrine” and from the tradition of social Catholicism. Only time will tell, however, if a Catholic community that has been misled into acting with the conservative side of the culture wars can recognize the dystopia to which that is leading and discover the Catholic way of informing the world with the spirit of the Gospel. For this, Fr. Maurice Ouellet, the Sisters of St. Joseph, and the other social Catholics about whom I have written provide trustworthy guides.

Edit: This video sheds more light on the Catholics who marched from Selma to Birmingham. MLK had contacted the Archbishop of St. Louis for support, and they sent a contingent of over 50 Sisters, Priests, and others.

*** Be sure to click the arrow in the black box marked “Watch on Youtube” at the lower left corner below, not the red one in the center of the screenshot, which requires you to be logged-in to youtube.***