Luke's Gospel of Reversal

Sunday's Lectionary Offers Timely Words of Both Hope and Condemnation

Together with those throughout the world who recognize the central role that the United States has played in promoting constitutional democracy, human rights and a rule-based international order, many Catholics are rightly alarmed at the systematic deconstruction of our public institutions following a “regime change” to some combination of autocracy and oligarchy in open sympathy with strongmen like Vladimir Putin.

With the attack on USAID spearheaded by the richest man in the world, a significant portion of those working for Catholic Charities and Catholic Relief Services now face unemployment. As a result, the Ukrainian people who were the largest recipient of USAID face abandonment by their primary ally. The international humanitarian aid infrastructure, moreover, is decimated leaving tens of millions of the world’s most vulnerable to suffering their cruel fate with little hope of assistance. At the same time, many of the most influential Catholic voices in the United States continue to signal their support for the political right by “punching left”—such as by signaling their opposition to “wokeness” or “DEI”—and by repeating hard-right “dog whistles.” Other Catholics follow their lead. Still others on the Catholic right are now rejoicing in their contribution to the “regime change,” relishing their proximity to political power, and reminding defenders of liberal democracy that they have suffered a historical defeat that threatens to profoundly change the course of history. This entails, for example, the end of the postwar Pax Americana centered in the alliance of constitutional democratic states.

As the attacks against our highest principles and institutions continue and bear their destructive fruit, one might hope that increasing numbers will recognize the rapidly escalating crisis, even if it is unclear what might be done. For prayerful Catholics, we look to the liturgy for the nourishment of Word and Sacrament.

The Sixth Sunday in Ordinary Time

At this pivotal time in human history, the Church’s lectionary offers us a rich and timely set of readings. In what follows, I will offer some very brief comments on these selections from the written Word of God, and indicate why I think they have considerable relevance for contemporary American Catholics. The Old Testament reading from Jeremiah 17:5-8 and the Responsorial from Psalm 1 mediate—through word and song—a fundamental insight of biblical ethics. This is that human life presents us with a choice between two ways or paths, one towards goodness and truth, and another towards evil. In so doing, the Church provides us with a moment of grace, in which to reconsider our place in the drama of human history and to make a fundamental choice about how we will respond. The Gospel reading is the Lukan account of Jesus’s Sermon on the Plain. As we will see, a key mark of the kingdom Jesus inaugurates is a “reversal” of fortune that I will relate to these two ways or paths.

Since the first reading from the Old Testament (Jer 17:5-8) and the Responsorial Psalm are close parallels, I will include below only the text of the Psalm, before focusing on the Gospel reading and concluding with some insights on the New Testament reading from 1 Corinthians 15. Whereas our text from Jeremiah distinguishes the “two ways” based on whether one trusts in human strength or in God, the Responsorial Psalm provides additional insights. The text follows.

Responsorial Psalm 1:1-6

Blessed are they who hope in the Lord.

Blessed the man who follows not the counsel of the wicked,

nor walks in the way of sinners, nor sits in the company of the insolent,

but delights in the law of the LORD, and meditates on his law day and night.

Blessed are they who hope in the Lord.

He is like a tree planted near running water,

that yields its fruit in due season, and whose leaves never fade.

Whatever he does, prospers.

Blessed are they who hope in the Lord.

Not so the wicked, not so;

they are like chaff which the wind drives away.

For the LORD watches over the way of the just,

but the way of the wicked vanishes.

Blessed are they who hope in the Lord.

While aligning with Jeremiah’s perspective by highlighting that the just have a fundamental trust and hope in God, this Psalm—which offers a kind of programmatic introduction to the whole Psalter—provides further insights into the two paths. Beyond our text from Jeremiah, it adds that the evil path is characterized by keeping bad company, including with those who counsel or encourage evil acts, and with those who are insolent in the sense of being rude and arrogant. The wicked are compared to the worthless chaff that “the wind drives away.” The blessed, on the other hand, are those who seek to a life of wisdom and justice, nourished by “delight[ing] in the law of the Lord,” and meditating on it “day and night.” The Lord “watches over” the way of these blessed such that whatever they do prospers, so their lives bear abundant fruit like a tree planted near running water. Other Psalms, including those we number as 37 and 73, reflect on the question of why the wicked often prosper while the just often suffer. For Christians, of course, this mystery of evil is more adequately explained only in light of the saving life, death and resurrection of Christ.

Contextualizing Our Reading within the Gospel of Luke

The theology of the Gospel according to Luke provides the proper context for understanding today’s Gospel reading. New Testament scholars like Frank Matera—upon whom I draw in what follows—agree that Luke was written for an audience of gentile Christians, with a goal of highlighting the assurance that the Gospel brings to those suffering afflictions. Thus, in his inaugural speech, Jesus cites the Prophet Isaiah:

The Spirit of the Lord is upon me, because he has anointed me to preach good news to the poor. He has sent me to proclaim release to the captives and recovering of sight to the blind, to set at liberty those who are oppressed, to proclaim the acceptable year of the Lord.” (Lk 4:18-19)

As in the other two synoptic gospels of Mark and Matthew, Luke emphasizes that the kingdom of God is “breaking in” through the person and work of Jesus. This kingdom is properly understood as the realm where God’s rule is present and operative; it is decidedly not a political alliance to coerce adherence to traditional morality such as that sought by Evangelical Christian nationalists or Catholic integralists. Instead, this kingdom is properly understood as an effective rule that is fully present in the person, words and works of Jesus. For the synoptic Gospels, this kingdom is becoming present in the lives of those who are beginning to believe. Luke shapes his account to emphasize—as in the infancy narratives—that a new age of salvation is “breaking in” in this kingdom proclaimed by Jesus.

Contrary to those who think it is consistent with Christian faith to support autocrats to enforce some understanding of moral order that runs fundamentally against justice and charity, this new age of salvation has profound ethical implications that are a fulfillment of what was foreshadowed in the Old Testament. This ancient ethic centered in justice and loving mercy is founded in the justice and love that is inseparable from God’s very being and requires that his covenant people honor the truth of every relationship. In this profoundly relational ethic that presupposes the creation of every person in the image of God, the test of honoring the truth of interpersonal relationality—and thereby living justly—is seen in how we treat the most vulnerable. In the Old Testament—which is fulfilled, not abrogated in the New—these most vulnerable are represented by frequent reference to the widow, the poor, the orphan and the stranger or alien.

In communicating the good news to an audience of mostly gentile Christians suffering affliction, the Gospel according to Luke emphasizes a reversal of fortunes that characterizes this new age of salvation. This reversal is illustrated, for example, in the barren Elizabeth giving birth to John the Baptist in her old age (1:7-26, 36-37, 57-80). It is also exemplified in Mary’s conception of Jesus through the Holy Spirit (1:26-56) and her Magnificat, which the Church includes in her evening prayer. Some key excerpts follow:

…for he has looked with favor on his lowly servant. From this day all generations will call me blessed: the Almighty has done good things for me, and holy is his name. …He has shown the strength of his arm, he has scattered the proud in their conceit. He has cast down the mighty from their thrones and has lifted up the lowly. He has filled the hungry with good things, and the rich he has sent away empty. (Lk 1:48-53)

This reversal of fortune between the lowly and mighty foreshadows the one we will see in the Lucan beatitudes. The inbreaking of this new age of salvation in the kingdom proclaimed by Jesus requires conversion (Greek epistrophe) in the sense turning around our lives to conform to God’s inbreaking rule. It also requires repentance (metanoia) which the synoptic Gospels present as a radical new way of thinking. Like the Gospel according to Mark upon which it relies, Luke understands this repentance to a radical new way of thinking to entail a change from a worldly one that seeks power and honor to Jesus’s way of becoming a servant of all. The baptism preached by John is, moreover, a baptism of repentance given the realization of God’s saving plan in Jesus (3:8ff).

The Lukan Jesus—who comes not for the self-righteous but to call sinners to repentance (5:32)—does so in many ways. He socializes, for example, with sinners needing repentance (15:1-2), and he uses the occasion of a shared meal to offer them three parables about the joy in heaven over repentant sinners (15:3-32). Key illustrations of repentance include not only the parable of the prodigal son (15:11-32) but also that of the Pharisee and the publican (18:9f).

Examples of those who—on the other hand—reject the invitation to repentance include Simon the Pharisee (7:39-46), the elder son (15:25-32), and the Pharisee who goes to the temple to pray (18:9-14). Jesus pronounces words of woe to the cities of Chorazin, Bethsaida, and Capernaum (10:13-15) as representing those who refuse to receive the Good News of God’s inbreaking kingdom marked by a new age of salvation and reversal for the oppressed.

Keeping in mind these key themes from the Gospel according to Luke, we can readily appreciate Sunday’s reading. A key point to note is that, compared to the parallel text of Matthew’s Sermon on the Mount, which presents the beatitudes in the “third person” (i.e., “those” or “they”) thereby inviting people to follow the example of Jesus, Luke presents them in the “second person” (“you”) as words of consolation.

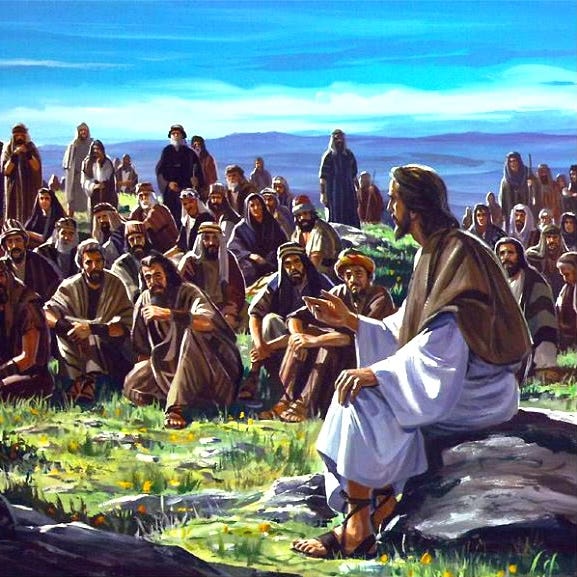

Gospel According to Luke 6:17, 20-26

Jesus came down with the Twelve and stood on a stretch of level ground

with a great crowd of his disciples and a large number of the people

from all Judea and Jerusalem and the coastal region of Tyre and Sidon.

And raising his eyes toward his disciples he said:

“Blessed are you who are poor, for the kingdom of God is yours.

Blessed are you who are now hungry, for you will be satisfied.

Blessed are you who are now weeping, for you will laugh.

Blessed are you when people hate you, and when they exclude and insult you,

and denounce your name as evil on account of the Son of Man.

Rejoice and leap for joy on that day!

Behold, your reward will be great in heaven.

For their ancestors treated the prophets in the same way.

But woe to you who are rich, for you have received your consolation.

Woe to you who are filled now, for you will be hungry.

Woe to you who laugh now, for you will grieve and weep.

Woe to you when all speak well of you, for their ancestors treated the false prophets in this way.”

Consistent with the broader message of the Gospel According to Luke, his presentation of the beatitudes conveys a powerful word of consolation and reversal of fortune.

How Might these Texts Invite Us to Enter Into the Mystery of Christ?

As they did for their original audience, our Old Testament texts encourage us to choose the path of faith and wisdom, which lead to a life that bears abundant fruit. The Gospel of Luke proclaims that God’s rule is breaking into human history through the person and work of Jesus who brings a new age of salvation. The beatitudes, moreover, offer hope to the multitudes of our day who are experiencing—or fearing—hunger, tears, hatred, exclusion, insults, and denunciations. On the other hand, our Gospel threatens a reversal of woe to the rich and powerful. Of course, this does not mean that God’s love excludes them, but it reflects the temptations and greater obligations that accompany the gifts with which some have been entrusted.

Beyond these basic considerations, however, the country and broader human family face unprecedented threats of what could be a dystopian future. Against this, Christ’s redemptive work is meant to be continued in the world by the members of his body the Church. Although this is essentially a work of grace so we can hope firmly in God’s assistance, we have been given responsibility over earthly affairs through which the drama of salvation history plays out.

Since especially the Second Vatican Council, the Church has encouraged Catholics to infuse the postwar world of constitutional democratic states with the spirit of the Gospel. To do so, the Church has articulated a social doctrine of “integral and solidary humanism” that reflects many generations of experience. Postwar Catholics living out this doctrine contributed significantly, moreover, to the creation of the postwar order that resulted in generations of relative peace and prosperity. During especially the last four decades, however, American Catholics have largely forgotten this social doctrine, and become part of a neoliberal economic and political paradigm in significant tension with that doctrine. To a significant degree, this neoliberal paradigm had been proven unsustainable by the time of the 2008 financial crisis, and has since evolved into some combination of oligarchy and autocracy.

Even if the signs of the times threaten a dystopian future, today’s reading from the First Letter to the Corinthians turns on the belief that Christ has indeed been raised from the dead. If we believe this is true, and if we believe that he has poured out his Spirit and established the Church as the visible manifestation of his kingdom, and if God is indeed the Lord of history, my hope and prayer is that Catholics will take to heart the graces of this liturgy and consider how they might play their role in informing the world with the spirit of the Gospel. For such a task, the social tradition of the Church offers many examples from which we can learn, along with tested set of principles, and a methodology of democratic collaboration in a spirit of integral and solidary humanism. By rediscovering this tradition, and with the help of God’s grace, we should be confident that the kingdom can still break into our world, and that the needed reversals can still be effected, and that God can do more than we can ask or imagine (Eph 3:20).