Pilgrims of Hope and Agents of Fraternity

An Authentically Catholic Response to the era of the Polycrisis

As is evident from his social encyclicals including the 2015 Laudato si’: On Care for Our Common Home (LS) and the 2020 Fratelli Tutti: On Fraternity and Social Friendship (FT), Pope Francis is acutely aware of the grave challenges that threaten the human family. In Laudato si’, for example, he deals frankly with the environmental crisis while in Fratelli Tutti he discusses the “dark clouds” and shattered dreams of the postwar efforts to build a more just and peaceful world.

We can be confident, therefore, that his choice of “Pilgrims of Hope” as the theme for the Jubilee year of 2025 should not be understood as the “happy talk” of a Pollyanna. It is more plausibly interpreted as reflecting one of the distinguishing virtues of the Christian life, which follows from our fundamental trust in the good God who created us in love, who redeemed us in Christ, who remains with us as Immanuel, and who has established the Church as a light to the nations. This call to be pilgrims of hope should also be seen, therefore, as part of Francis’s pastoral ministry in service to the people of God, encouraging us to exercise the Christian virtue of hope, especially if dark clouds threaten.

Given that this substack similarly strives to deal forthrightly with what has increasingly come to be described as the global polycrisis, I wanted to begin the New Year by highlighting the central Christian virtue of hope, which reminds us to trust in the God who “…can do infinitely more than we can ask or imagine” (Eph 3:20). Before introducing our Jubilee Year of Hope, however, I will briefly contextualize it in light of an earlier jubilee when I officially began my work in the Church as a moral theologian, and when the ecclesial, national and global situations made it much easier to hope. I do so based on the belief that understanding how we got from there to here is the first step in fending off—with God’s help—the dystopian future that threatens.

From the Great Jubilee of 2000 to the Global Polycrisis

Besides the Extraordinary Jubilee of Mercy that Pope Francis announced in 2015, which was a relatively minor event in the recent life of the Church, the Great Jubilee of the Millennial Year 2000 was a monumental time in many respects: in the Church, in the beginning of my work as a moral theologian, and in the world.

In the Church, Pope John Paul II significantly ordered his Pontificate not only to fostering the reception of the Second Vatican Council, which he saw as bearing fruit in a New Evangelization. He also ordered his pontificate toward the new millennium to be inaugurated by the Great Jubilee year of 2000. In his Apostolic Letter Novo Millennio Ineunte: At the Close of the Great Jubilee of the Year 2000, he called for a new springtime of evangelization through the Gospel image of putting out the nets for a great catch of fish.

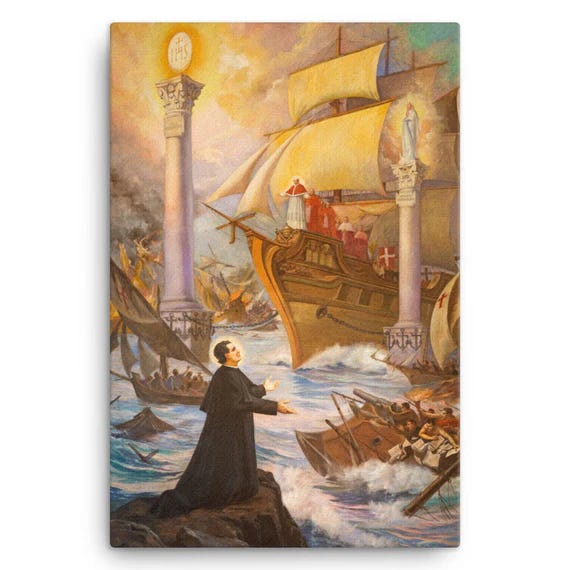

In my own life, May of 2000 marked the completion of my Doctorate in Sacred Theology from the Pontifical John Paul II Institute for Studies on Marriage and Family. Immediately after my dissertation defense, I rushed to the airport to catch a flight to Rome for a series of events organized by the Lateran University—which housed the central “Roman session” of the Institute—to celebrate the Jubilee. These events began with almost front-row seats for the canonization of Sr. Faustina, the first saint of the new millennium. With my fellow graduates, we then continued with a gathering at a rooftop apartment with a view of St. Peter’s Basilica in Vatican City. For we convinced “JPII Catholics” of that time, the vision that St. John Bosco received in a dream was being fulfilled before our very eyes. According to this vision, the Church was symbolized as a ship—with the Holy Father on the bow—guiding the Church through rough waters and assaults to safety between the two pillars, with the Eucharistic host atop one and Our Lady atop the other. I began my career that summer as a moral theologian with a postdoctoral fellowship in the Department of Philosophy at the University of Notre Dame, and with great hope for a future in which the Church had regained her footing, and had sufficiently received the Second Vatican Council to foster the living out of the Universal Call to Holiness and to infuse the spirit of the Gospel into world.

[The Prophetic Vision of St. John Bosco. Catholiccompany.com]

In the broader world, we were roughly a decade past the collapse of Soviet Communism. In subsequent years, international coalitions led by the United States had successfully confronted military aggression in both Kuwait and the Balkans. The threat of economic and societal disruption from the Y2K computer glitch, moreover, had been successfully addressed by a global, public-private effort, further solidifying public confidence in expertise and institutions. With the smooth transition of continental currencies to the Euro in 1999, the realization of the postwar dreams of a peaceful and prosperous future seemed to be proceeding steadily. The unfolding of globalization, moreover, promised to expand these blessings to all. It seemed that the triumph of constitutional democracy—building on the American model—offered a proven framework for the world, and Francis Fukuyama provoked a famous discussion about whether the evolution of political systems had reached a kind of “end of history” with the consensus for liberal democracy. Even more important for “JPII Catholics,” the Catholicism of John Paul II seemed to be realizing the hopes of the Second Vatican Council for the Church as a sacrament of unity in the World (Lumen gentium: Dogmatic Constitution on the Church, no. 1).

From Early Signs of Trouble to the Contemporary Polycrisis

Shortly after the start of my second year at Notre Dame, however, more troubling developments began with the terrorist attacks of 9/11/2001. These soon led to the so-called “War on Terror,” and the disastrous military adventures of the George W. Bush Administration, which prominent Catholics promoted against the strong public objections of Pope John Paul II. With especially the 2003 invasion of Iraq, the credibility of the United States as a responsible participant in the community of nations suffered immense harm. In between these events, the reputation of the Catholic Church in the United States, had already been blackened by perhaps the most shocking of an ongoing series of scandals. This reputational catastrophe came through the January 6, 2002 publication in The Boston Globe of the results of their intrepid Spotlight investigation of the twofold scandal of sexual abuse by clergy and systematic coverup by bishops. By 2008, as the Bush Administration petered out amidst the worst economic crisis since the Great Depression, there were already good reasons to fear that the neoliberal paradigm under which the recent decades of globalization had unfolded was unsustainable. Given the close alliance of the Catholic “theoconservatives” with the social, economic and geopolitical agenda of the Republican party of this era, they too were largely discredited, at least in the eyes of those paying attention. The key questions for thoughtful observers were how a millennium that started out with such promise was going increasingly downhill, and—perhaps more importantly—how to chart a better course for the future.

In the introduction to my new edited collection Social Catholicism for the Twenty First Century? Volume 1 Historical Perspectives and Constitutional Democracy in Peril, I complement Pope Francis’s reading of the “signs of the times” in Fratelli Tutti with contemporary discussion of the so-called “polycrisis” that has subsequently developed. I build on the Holy Father’s discussion of the disappointed hopes of the postwar era by drawing upon the influential analysis of Adam Tooze, who popularized this term through his keynote address at the 2023 Davos meeting of the World Economic Forum. For Tooze, this global polycrisis can be understood as an interconnected set of crises with economic, technological, environmental, political, geopolitical, sociopsychological, and informational dimensions.

The above graphic corresponds to the year of Tooze’s keynote, with that for 2024 showing similar risks and that for 2025 expected in the upcoming days. Tooze speaks and writes of how this polycrisis risks spinning out of control unless it is well-managed by competent leaders directing robust public institutions. He illustrates the management of the polycrisis through the image of managing a nuclear reactor, and the fundamental importance of who is at the controls. In our time of populist leaders spewing division and disinformation—and deliberately destroying the public institutions that have been shown to be foundational to upholding the common good—the key to managing the polycrisis is to ensure that competent leaders are in place to “manage the reactor.”

[Homer Simpson Asleep at the Controls. 20th Century Television. From looper.com]

Few contemporary American Catholics, however, understand how the Church helped to build the postwar consensus that made real progress toward a more just and peaceful world. Few contemporary Catholics, moreover, have an effective understanding of how Catholic Social Doctrine offers us a path to work for societies marked by justice, solidarity, respect for the dignity of every person, and social friendship. Nor do we sufficiently understand how an alternative social vision has not only led to the polycrisis, but helped to render the social doctrine of the Church unintelligible to many Catholics. Showing little awareness of the contemporary blending of oligarchy and propaganda, some of our country’s most influential Catholic leaders continue to encourage us to prioritize the threat of “wokeness,” for example. At the same time, the broader institutional Church has so neglected the authentic social doctrine of the Church that Catholics have ordered their political engagement toward seeking tax cuts or expressing anger about the price of eggs. Rather than seeking the most competent and serious leaders to “manage the reactor,” the majority of American Catholic voters have just helped to elect an aspiring autocrat in alliance with a network of oligarchs and global strongmen. What could go wrong?

It is into this quite different context that Pope Francis has called for a Jubilee year of hope. In what follows, I will draw selected quotations from Spes non confundit: Bull of Indiction for the Ordinary Jubilee Year of 2025, the Latin title of which means “hope does not disappoint” (Rom 5:5).

Pilgrims of the Hope that Does Not Disappoint

Not surprisingly, the Holy Father begins by expressing his desire that the Jubilee to “be a moment of genuine, personal encounter with the Lord Jesus,” through which we are “renewed in hope” (no. 1). He wisely draws in no. 2 upon St. Paul, whose theology is—in many respects—the richest in Scripture.

“Since we are justified through faith, we have peace with God through our Lord Jesus Christ, through whom we have obtained access to this grace in which we stand; and we boast in our hope of sharing in the glory of God… Hope does not disappoint, because God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit that has been given to us” (Rom 5:1-2, 5).

This text merits meditation as, for St. Paul, the Holy Spirit is likened to a “down payment” (Greek ἀρραβών, pronounced arrabón) on the work of sanctification and reconciliation that God is doing in and through us. We can draw confidence that this work is being done in us as we participate in the pattern of sacrificial love exemplified by Jesus.

In no. 3, Francis draws on the eighth chapter of Paul’s Letter to the Romans with its rousing reflection on Christian hope:

“Who will separate us from the love of Christ? Hardship, or distress, or persecution, or famine, or nakedness, or peril or the sword? No, in all these things we are more than conquerors through him who loved us. For I am convinced that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor rulers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord” ( Rom 8:35, 37-39).

It is precisely this hope, “founded on faith and nurtured by charity” that “enables us to press forward in life” (no. 3).

Number 4 focuses on the “realism” of authentically Christian hope that faces not only the joys of life but also the struggles and sorrows that are part of the human condition. Regarding this realism of hope, Francis draws upon not only St. Paul in Romans 5:3-4, who writes that “We boast in our sufferings, knowing that suffering produces endurance, and endurance produces character, and character produces hope”. He also draws upon Paul’s Second Letter to the Corinthians, regarding how hope is likened to patience. This letter contains the most extensive New Testament reflections on how the divine power is at work in the lives of Christians. Paul likens the Christian life as “earthen (i.e., clay) vessels” carrying treasure (2 Cor 4:7, RSV). He describes this life as one of continually carry in our bodies the dying of Jesus, so that the life of Jesus might also be manifested in our bodies (4:10).

Numbers 5 and 6 of Spes non confundit are organized under the heading of A Journey of Hope, with the latter number laying out the calendar for the Jubilee year. The first number, on the other hand, reminds us that:

“This interplay of hope and patience makes us see clearly that the Christian life is a journey calling for moments of greater intensity to encourage and sustain hope as the constant companion that guides our steps towards the goal of our encounter with the Lord Jesus.”

The journey of Jubilee events includes pilgrimage as a “fundamental element,” which can be an opportunity for “silence, effort and simplicity of life” (no. 5). Pilgrimage to Rome can be an opportunity for not only reconciliation but also communion with the universal Church.

Numbers 7 through 15 of Spes non confundit are presented under the heading of Signs of Hope. Number seven encourages us to find hope in the “signs of the times,” which might seem surprising given what I wrote above about them. This hope starts with the need to “recognize the immense goodness present in our world, lest we may be tempted to think ourselves overwhelmed by evil and violence.” Francis also thinks we need to recognize even “the yearning of human hearts in need of God’s saving presence” should be seen as “signs of hope.” In this, he captures a fundamental feature of many Psalms as discussed by prominent Old Testament scholars like Walter Brueggemann. In these Psalms, crying out to God for help in misfortune, and for justice against oppressors, is quintessential to biblical prayer. Number 8 emphasizes that we should also see the widespread human “desire for peace in our world” as a sign of hope. The longings in the human heart for justice and peace have been placed there by God to orient us to our fulfillment, of which these are integral parts.

On the other hand, “the loss of the desire to transmit life” and “an alarming decline in the birthrate as a result of fears about the future, the lack of job security and adequate social policies” are ominous signs of a loss of hope, which follows naturally from a world accelerating down an obviously unsustainable path. Francis affirms that “the Christian community should be at the forefront in pointing out the need for a social covenant to support and foster hope…” (no. 9). Such a covenant in which we join together in solidarity to build a future worthy of the human family follows precisely from the Catholic Social Doctrine that guides the Holy Father.

Francis calls us to be tangible signs of hope during the jubilee year through the traditional works of mercy, which he wants us to see as “works of hope” (no. 11). Through these works of mercy, we would thereby be signs of hope for especially those experiencing hardships including prisoners (no. 10), the sick (no. 11), and the homebound (no. 11). Although the young are normally inclined toward hope, Francis calls us also to be signs of hope to them because today they “often see their dreams and aspirations frustrated,” and frequently “face an unpromising future” because they often “lack employment or job security, or realistic prospects after finishing school” (no. 12). Francis also calls us to be agents of hope for migrants, for exiles, and for displaced persons and refugees (no. 13). He further exhorts us to make these acts of mercy and hope to the most vulnerable (no. 13). In this, he aligns perfectly with the central Old Testament prioritization the poor, the widow, the orphan and the stranger. Because he does not abolish the law, but fulfills it, this priority on the most vulnerable can be seen in Jesus’ teaching that we serve him when we serve “the least of these brothers and sisters.” Francis similarly calls us to be ministers of hope for the elderly in no. 14, and for the poor in no. 15.

In the next subsection, Francis makes Appeals for Hope directed to those who are in the best position to do so. He does so by drawing on the prophetic tradition to remind us that the goods of the earth are meant for everyone. On this basis, Francis directs his appeal to especially wealthy individuals and wealthy nations (no. 16), whom he exhorts to take the lead in bringing hope to their impoverished brothers and sisters by sharing the bounty of which God has appointed them stewards. He reminds us that “[m]ore than a question of generosity, this is a matter of justice” (no. 16). Francis mentions, for example, the “ecological debt” that exists between wealthy nations in the North—that have done a disproportionate share of ecological damage—and poorer nations in the South, that will suffer the greatest consequences.

In a reference to political participation, he writes “If we really wish to prepare a path to peace in our world, let us commit ourselves to remedying the remote causes of injustice, settling unjust and unpayable debts, and feeding the hungry.”

After noting the 1700th anniversary of the great Ecumenical Council of Nicea in no. 17, the remainder of Spes non confundit (nos. 18-25) is under the subheading of Anchored in Hope. The first paragraph (no. 18) locates hope within “the triptych of the three “theological virtues”—namely faith, hope and charity—that express the heart of the Christian life (cf. 1 Cor 13:13; 1 Thess 1:3).” From here he introduces a reflection on “‘the reasons for our hope’ (cf. 1 Pet 3:15).” These reasons begin with our belief in life everlasting, which leads us to live in expectation of Christ’s return in glory (no. 19). This life of expectation follows from our belief in the death and resurrection of Jesus (no. 20), and from the fact that we were “buried with Christ” in Baptism so that “we receive in his resurrection the gift of new life that breaks down the walls of death...” The martyrs, moreover, provide “[t]he most convincing testimony to this hope.” After death, moreover, we are confident that “[a]ll that we now experience in hope, we shall then see in reality” (no. 21). Francis writes that

The coming Jubilee will thus be a Holy Year marked by the hope that does not fade, our hope in God. May it help us to recover the confident trust that we require, in the Church and in society, in our interpersonal relationships, in international relations, and in our task of promoting the dignity of all persons and respect for God’s gift of creation. May the witness of believers be for our world a leaven of authentic hope, a harbinger of new heavens and a new earth (cf. 2 Pet 3:13), where men and women will dwell in justice and harmony, in joyful expectation of the fulfilment of the Lord’s promises.

Let us even now be drawn to this hope! Through our witness, may hope spread to all those who anxiously seek it. May the way we live our lives say to them in so many words: “Hope in the Lord! Hold firm, take heart and hope in the Lord!” (Ps 27:14). May the power of hope fill our days, as we await with confidence the coming of the Lord Jesus Christ, to whom be praise and glory, now and forever.

There are many rich sources for reflection on the theological virtue of hope in the Christian tradition, and I will draw upon them frequently during the coming year. As we begin the New Year, reflection on Spes non confundit can get us off to a good start in living this Jubilee Year as Pilgrims of Hope and witnesses to hope, who are nevertheless realists about the challenges facing the human family.