Small Government Libertarian Defends State Capacity

A Growing Coalition to Defend our Public Institutions Against the DOGE Chainsaw?

In this post, I will illustrate the possibility of a broad coalition of those striving to defend our public institutions from the unprecedented attacks against them. Because these attacks gravely threaten the common good, they should be of acute concern to everyone, so the potential for such a coalition is vast. Whether such a coalition can form, however, depends upon overcoming various obstacles.

There are those, however, who mistakenly—in light of Catholic thought and, I would add, right reason—consider their personal good to be distinct from the common good. These have most often been of libertarian leanings, often under the influence of Ayn Rand. Indeed, the techno-libertarians associated with Silicone Valley and “Big Tech” often reflect the influence of such thought.

It is encouraging to see, therefore, a strong defense of our public institutions by an established figure in libertarian and Randian circles. We get exactly that from Robert Tracinski who is a columnist for Discourse Magazine which is published by the largely libertarian Mercatus Center. He is also a senior fellow at The Atlas Society, a home for Randian thought. I think Catholics should welcome Tracinski’s defense of what he calls “state capacity,” even if I think we should be critical of libertarianism and Randianism. This follows from the fact that social Catholicism is inherently non-ideological and non-partisan, which doesn’t prevent us from supporting the political parties we think best serve the common good. Social Catholicism is also marked by friendly dialogue with all sources of knowledge, and a long tradition of broad collaboration, including with those with whom we have important disagreements.

[David Harth, Marvel]

Before getting to Tracinski’s post, I will first provide links to previous posts that recall how modern Catholic Social Doctrine developed in concert with the evolution of modern states characterized by their various institutions, and how this model results in relatively flourishing societies as distinguished from failed states. I will also provide a link to a previous post that discusses the origins of a broad and long-term campaign of persuasion—that is, propaganda—to oppose such a vision in order to maximize the political and economic power of the wealthy.

This historical background will help us to appreciate the importance of Tracinski’s defense of public institutions as the means through which we achieve various kinds of “state capacity.” Given the dystopia that the current anti-institutionalism threatens, perhaps new language can open a path toward collaboration in building a future worthy of the human family.

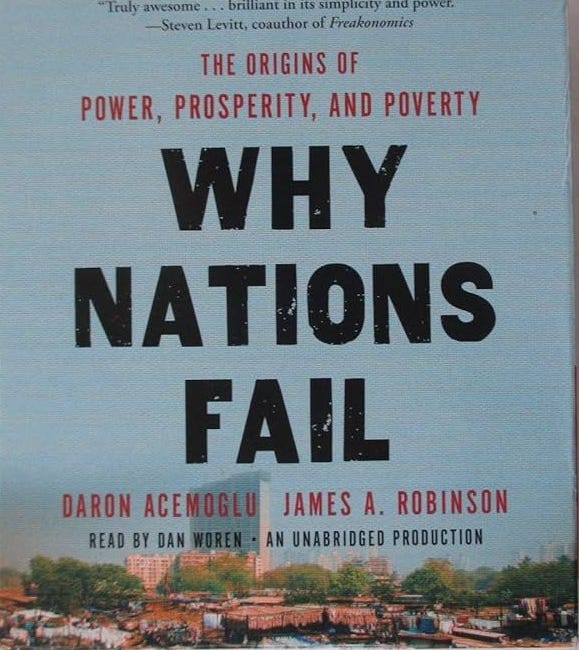

The following post, which I published in October, showed how both recent Catholic social teaching and the most recent Nobel Prize in Economic Science align with the defense of institutions offered by Tracinski.

Benedict XVI and the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences

I have mentioned in previous posts the programmatic call of Pope Benedict XVI in the introductory section of his 2009 social encyclical Caritas in veritate: On Integral Human Development in Charity and Truth. The core of number 7, reads as follows (emphasis in the original):

In earlier posts, I discussed how the broader tradition of modern Catholic social teaching comes to appreciate the importance of the institutions that provide that state capacity.

Although the first modern social encyclical, Leo XIII’s Rerum Novarum: On Capital and Labor (1891), still looked back nostalgically to the loss of Catholic institutions like the guild, and although it still preferred to speak of the institutions of civil society over government ones, it did open a path for the later expression of explicit support for their ongoing development. Rerum Novarum did so by directing governments to intervene when necessary to remedy the key social injustices that were undermining the common good, such as wages that failed to provide for sustenance, unsafe working conditions, and excessive working hours. It also did so by providing a broad understanding of the common good, the implications of which would better understood over time. The reception of Rerum Novarum in the United States was led by Msgr. John A. Ryan, who collaborated with a wide range of Progressive Era social reformers, just as the European social Catholics worked in broad and sometimes surprising alliances to foster the common good.

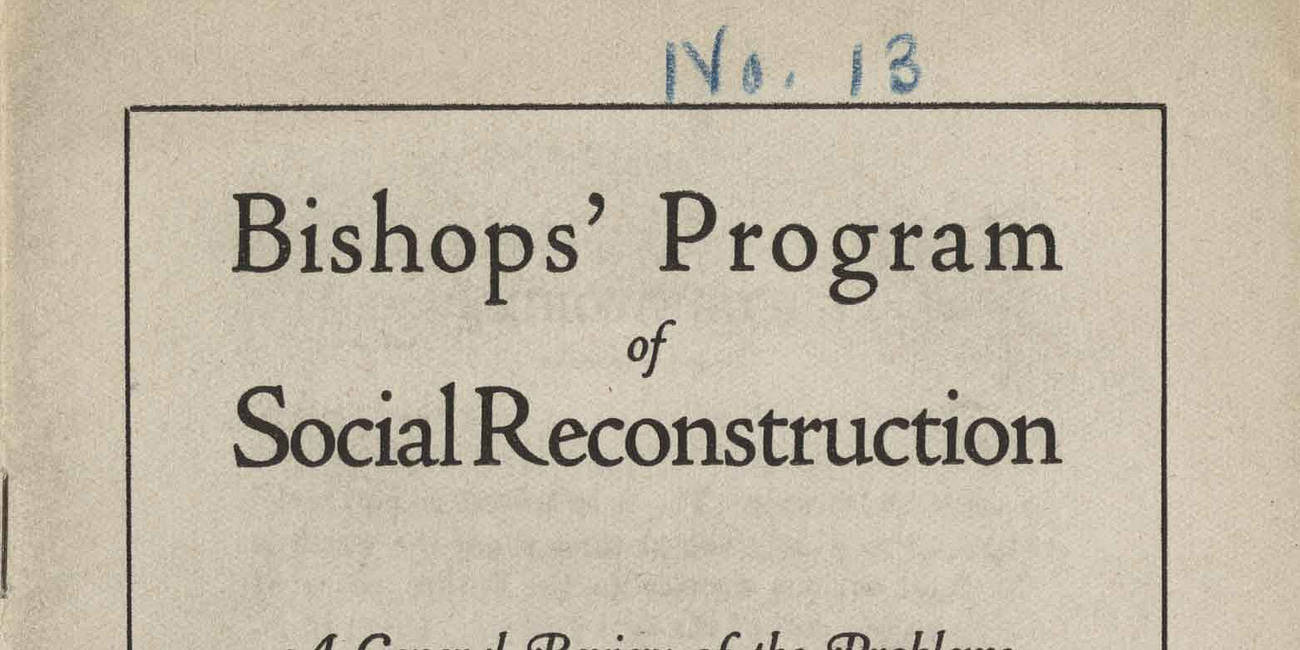

After the First World War, Ryan wrote a program of reform for the American Bishops that reflected his participation in an international and ecumenical conversation. The program included much of what would become common in the “mixed economies” or “social democratic” states that became an ideal after the Second World War. Ryan’s 1919 document is treated in the following post. It included key elements that might have prevented not only the Great Depression, but the Second World War, but it met stiff opposition.

Bishops as Prophets of Social Catholicism

In recent posts, I have sought to foster a renewed appreciation of the tradition of social Catholicism that has both inspired and embodied the Social Doctrine of the Church, a doctrine that has developed out of the deepest wellsprings of the Catholic faith.

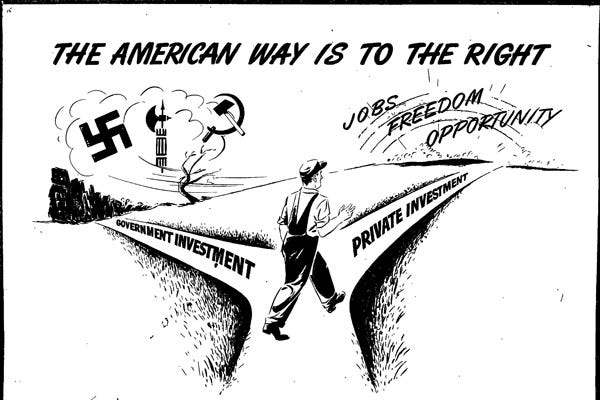

As I have also previously written, such reform efforts were strongly opposed by many business leaders starting in the 1920s. As Naomi Oreskes and Eric Conway show, they countered such progressive reforms with a growing program of propaganda to convince Americans that government intervention threatened oppression, as reflected in the left pathway below, whereas the mythical “free market” promised freedom and opportunity, if we follow the righward path. The freedom it delivered, however, was for the rich and powerful to dominate the poor and vulnerable.

The Counterattack of "the Big Myth"

In my previous post, I offered a detailed synopsis of the “1919 Bishops’ Program of Social Reconstruction” as an example of practical proposals that emerged from the participationist, reformist, and dialogical approach of social Catholicism. I showed how this document emerged from an ongoing solicitude for the great problems facing the human family, whi…

Following the tragedies of the Great Depression, the rise of Fascism, and the Second World War, the world was ready to embrace a new political economic paradigm. This took the form of President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s New Deal in the United States and christian or social democracy in Europe. This paradigm delivered an era of unprecedented peace and prosperity until champions of “market fundamentalism” returned to power following the economic stagflation of the 1970s. This resulted in forty years under a neoliberal paradigm. Although this was largely discredited in the 2008 financial crisis, it has remained in place. Just like it did in the 1920s, this paradigm has led to growing economic inequality, the rise of oligarchical and authoritarian leaders who are undermining the public institutions that defend human rights and dignity. In this context, Tracinski offers his defense of “state capacity.” In it, he build’s on economist Tyler Cowen’s 2020 introduction of the notion of “state capacity libertarianism.”

In his essay, Tracinski illustrates the fruitful dialogue that is possible between today’s “supply side progressives” and “state capacity libertarianism.” Such rational dialogue offers a valuable resource for aspiring social Catholics as they work for the common good.