The Church and Modernity in America

Revisiting a Historical Controversy between Reconstructionists and Reformists

In this post, I will introduce Martin Schlag’s “Johnny versus Tommie: What We Can Learn from a Historical Controversy about God in Modernity” which is published as chapter 4 in Social Catholicism for the 21st Century? Volume 1 Historical Perspectives and Constitutional Democracy in Peril. Of course, this introduction is meant not as an alternative to reading his insightful essay, but as an encouragement to do so.

Schlag explains that he is using the main title, “Johnny versus Tommie,” as a cipher which he explains as follows:

“Johnny” stands for St. John’s University in Collegeville, Minnesota, traditionally an institution of higher education associated with German-American Catholics; “Tommie” for the University of St. Thomas in St. Paul, Minnesota, traditionally linked to its founder Archbishop John Ireland and the Irish Catholics.

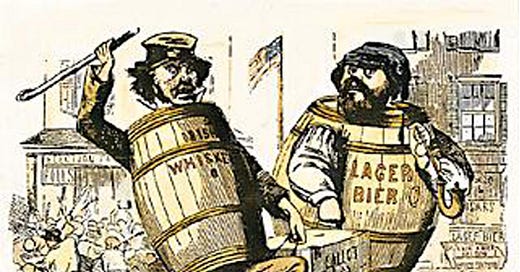

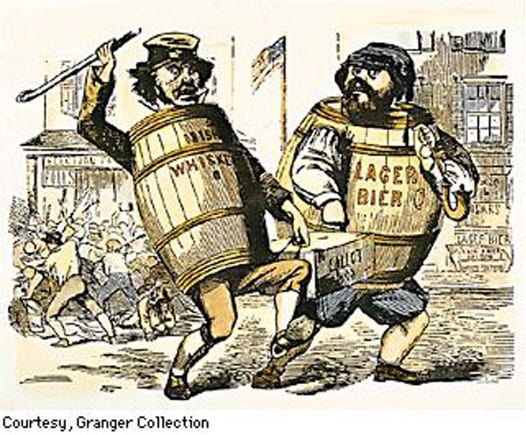

The “historical controversy” of the early 20th century centered in a disagreement between these two immigrant communities about how their shared Catholic faith would have them understand and relate to the political, economic and social arrangements in the United States. In a nutshell, the German-American Catholics (hereafter Germans) took a conservative, “reconstructive” stance where the Irish-American Catholics (hereafter Irish) took a liberal, reformist stance.

Schlag revisits this controversy, not merely as a point of historical curiosity, but for the light it sheds on the challenges facing us in the twenty first century. Whereas the previous century was marked by an atheistic humanism that sought to advance upon the Enlightenment while consigning religion to the past, ours threatens to be one marked by antihumanism. As such, it threatens to reject the key achievements of the enlightenment, including the dignity of reason, constitutional democracy, and the universal recognition of the human rights that protect the dignity of every human person. The task of the Church is to carry out her mission in a way that helps to protect and recover these authentic achievements, and their harmony with faith.

Conservative, Antiliberal and Reconstructive

The stance of the Germans was conservative, beginning with the sense of being fundamentally opposed to liberalism. As Schlag explains, “…liberalism was their enemy, and thus so was its economic expression, capitalism,” which at the time was a largely unregulated laissez faire economic order that the German Catholics not unreasonably saw as inseparable from a society marked by individualism. Schlag further writes, however, that:

In the imagination of the social romanticists of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the medieval corporations worked together harmoniously under the leadership of the clergy without class struggle or strife. All were building up the body of political society, which was meant to reflect the Church as Mystical Body of Christ. Central-Blatt and Social Justice is full of articles that demand both a radical change of heart and a radical reconstruction of the structures of the economy.

The economic and social thought of these Germans traced back to the “solidarism” of Fr. Heinrich Pesch, SJ, whose call for reform of both institutions and morals would be reflected in Pius XI’s 1931 social encyclical Quadragesimo anno: On the Reconstruction of the Social Order, which was published in the wake of the Great Depression. The antiliberalism of these Germans—which were allied with calls for radical reconstruction—seemed to have magisterial warrant, and thus reflected the predominant Catholic position. It was, however, largely abandoned after the interwar experience with fascism—which far too many Catholics supported and far too few opposed—and the resulting Second World War. After this humbling, tragic, and educative experience, the social teaching of the Church takes a clearly reformist and participationist stance in support of constitutional democratic states and human rights.

The conservatism of the Germans also contributed to their affirmation of a certain reading of the founding values of the American constitution. This reading, however, prioritized “states’ rights” as originally championed by “planters” in the American South to protect their social, political and economic order, which was originally based on slavery and later on “Jim Crow” segregation.

Liberal, Americanist, and Reformist

The Irish took what was called a liberal or Americanist stance because they fundamentally accepted the American political order. Given the opposition to liberalism and modernism that had developed in the Church since the French Revolution, this put them in a precarious position within the Church. Having escaped the poverty, hunger and political oppression they endured in the Old World, however, these Irish-Americans understandably appreciated their vastly improved situation in the New World. They saw a future in America, not just for them, but as a model for the broader Church.

Although the Irish similarly rejected the laissez faire economics, the individualism, and the Protestant shaping of American culture, they sought reform through participation in society and the political process, not through radical reconstruction. I would add that they followed the program of immigrant Archbishop John Ireland of striving to “make America Catholic” precisely by taking the lead in resolving the great social and economic challenges of their day. In so doing, they aligned with the tradition of Abraham Lincoln, Theodore Roosevelt and Franklin Delano Roosevelt that sought to employ federal power to rectify the imbalance between that of the wealthy and that of the vulnerable. In this I would note that they departed from the “states’ rights” model advocated by the Germans, which had not only allowed racial exploitation, but could foster economic exploitation by preventing federal legislative remedies.

Through the trajectory established among the U.S. Catholic Bishops, especially through the work of Archbishop Ireland’s protege Msgr. John A. Ryan, this reformist perspective was well-represented by the Catholic Church in the United States, at least until a more conservative turn took hold beginning in the 1980s. Our controversy between immigrant communities is of ongoing relevance, therefore, because the Church has continually faced this same choice the since the emergence of liberal states.

I would argue that a reconsideration of this fundamental choice is especially urgent today because the conservative stance of influential American Catholics has become increasingly antiliberal. To support the contemporary American right is far different than supporting the “fusion conservatism” of the Reagan era, as discussed in various chapters of Volume 1 Historical Perspectives and Constitutional Democracy in Peril. This confronts Catholics with the need for careful discernment. Should contemporary American Catholics continue down the conservative and reconstructionist path or should they recover the participationist and reformist one?

Discernment: the Magisterium and Intellectual Inquiry

Schlag considers the contemporary relevance of our historical controversy with reference to the teaching of the Second Vatican Council, Pope Benedict XVI’s hermeneutic of reform, his own proposal for “a hermeneutic of evangelization that struggles for social justice” corresponding to the emphases of Pope Francis, and the insights of various scholars. I will provide only a brief sketch so readers can consider the much richer discussion in Schlag’s chapter.

Despite the disappointing historical developments in the Church and world since the Council, Schlag affirms the ongoing importance of Council teaching on the Church in the postwar world. Because this postwar world is largely that shaped by the liberalism of the American Revolution, this conciliar teaching relates directly to our debate between German reconstructionists and Irish reformists.

He draws adroitly on Joseph Ratzinger’s understanding that key Vatican II documents—including Gaudium et spes: Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World—function as a kind of counter to Pope Pius IX’s 1864 Syllabus of Errors. In so doing, they replace “the Church’s critical reserve against modernity with the conviction that the Church needs to join forces with it.” Schlag understands this joining forces in terms of the Council’s articulation of the Church’s role in the world as something “carried out by all God’s people,” who “are leaven in the world,” sanctifying it through their secular activities and thereby sanctifying themselves. This is sanctification as leaven in the world clearly points to the participatory and reformist model and away from the reconstructionist one that would impose another order through coercive power following from a new alliance with political power such as that advocated by contemporary postliberals and integralists.

Schlag similarly draws upon Pope Benedict XVI’s “hermeneutic of reform” that the German Pope applied precisely to another part of his conciliar counter-syllabus of errors, namely Dignitatis humanae: Declaration on Religious Liberty. Against the hermeneutic of continuity that would require interpreting Dignitatis humanae in continuity with the rejection of liberalism and religious liberty by the Syllabus of Errors, Benedict’s hermeneutic of reform allows the Church to “update” the teaching of the Syllabus in through a recovery of the original Christian position. This original position was certainly not the later “integralist” union of spiritual and temporal power; this is at least implicit in the New Testament affirmations that Jesus’ kingdom is not of this world (Jn18:36), and that Christians should render to Caesar what is Caesar’s and to God what is God’s (Mt 22:21).

Beyond Benedict’s hermeneutic of reform, Schlag proposes that we “now need a hermeneutic of evangelization that struggles for social justice but also shares the faith, as Pope Francis has been pointing out.” This is the understanding we also find in the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church, where the second chapter presents the Church’s mission of evangelization and social doctrine as inseparable. In other words, we evangelize precisely by working for justice. Conversely, an understanding of evangelization without corresponding work for justice—such as an essentially apologetic or intellectual one—is at best incomplete from a Catholic perspective. It could even undermine an evangelization of culture if, for example, it were corrupted by ideology. Schlag’s insight about the integration of evangelization and work for justice, once again, supports the participationist and reformist model of Catholic Social Doctrine.

Schlag’s essay includes many other insights worth careful consideration. These include his proposal of a recovery of natural law—the right reason that rules and measures human acts—precisely to defend the humanism under threat in a century tempted by antihumanism.

If there is any doubt regarding the proposed resolution to the controversy, Schlag closes with support for the general reformist direction taken by the Irish-Americans under the leadership of Msgr. John A. Ryan.