Reminder: readers can view the following post, and dozens of other ones, at the Social Catholicism and a Better Kind of Politics website.

In what is arguably the most complex and tumultuous time in human history, one that has been increasingly called the polycrisis, the magnitude and diversity of the challenges facing the human family can easily lead to disorientation, to paralysis, or even to depression. I think a strong Catholic identity and a thoughtful openness to the discernment of the teaching office of the Church can instead help us to not only maintain our psychological and spiritual equilibrium. These can also assist us in our discernment about how to respond to the signs of our times so we can be the sources of hope, reconciliation, and healing that the world so desperately needs.

In recent decades, however, too many American Catholics have adopted identities that have obstructed them from rightly reading the signs of the times or responding wisely to them. Rather than manifesting the incarnation of divine love in the world, living out the integral and solidary humanism of Catholic Social Doctrine (CSD), and thereby building a world marked by social friendship, Catholics have too often been misled into identifying as part of the conservative side of the culture wars. In so doing, many Catholics have played key roles in handing over American constitutional democracy to some combination of autocracy and oligarchy, which threatens a dystopian future for the human family.

Rather than receiving Catholic Social Doctrine as understood by the magisterium, and rather than benefiting from the discernment of the Church about the signs of the times, we have also just witnessed a pontificate during which many of the most influential American Catholics manifested open antagonism toward Pope Francis and his initiatives, which were often rooted in CSD.

The many gifts that Pope Leo XIV brings to his new ministry, including his deep familiarity and identification with the Catholic Church in the United States offer an opportunity for a new start. At such a time, I think a deep reconsideration of identity—and of how that relates to not just the reception of Catholic Social Doctrine, but to receiving the discernment of the magisterium regarding the signs of the times—can facilitate this new start for the Church and the world.

In what follows, I will introduce four sources that can help us appropriate a properly Catholic identity and thereby align our thinking with the deepest wellsprings of revelation mediated through the Church, so we can bear the fruits of reconciliation and peace toward which the Church is ordered (See Lumen gentium no. 1). The first of these sources is St. Paul, who provides us with the richest biblical account of the human person created in the image of God. In this account, the Christian is transformed to be able to discern what is good and true (see Rom 12:2). The second source is Henri de Lubac, whose work is deeply informed by Pauline thought and spirituality and also influences the Christocentrism of the Second Vatican Council. I draw primarily on de Lubac’s recovery of the patristic and traditional understanding being a vir ecclesaisticus, literally a man of the Church, who not only thinks out of the tradition, but with the Church. The third is the angelic doctor, St. Thomas Aquinas, whose philosophically rich anthropology and virtue ethic offer an invaluable complement to Pauline Christocentrism and ethics. Aquinas’s work also provides a basis for explaining how our discernment is corrupted by unmoderated passions. Fourth, I will briefly note several champions of social Catholicism with whom we would do well to identify.

1. Identity and Discernment in St. Paul

St. Paul’s writings reflect his knowledge of not only the Old Testament through his deep reflection upon the Greek translation called the Septuagint. His writings also reflect his familiarity with stoic thought of the first century that placed considerable emphasis on identity formation and recognized that our deliberation and action depended on our character and identity.

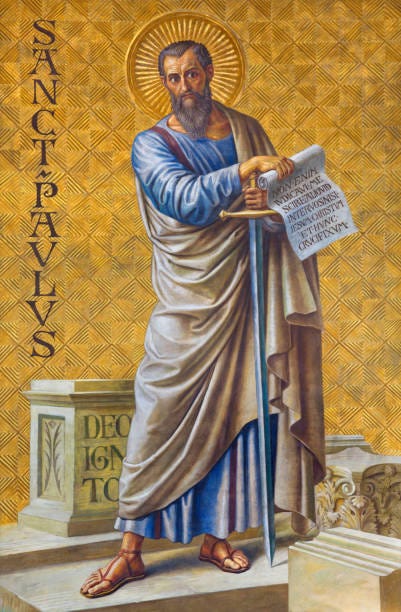

[Fresco St. Paul in Herz Jesus church, Berlin by Stummel and Wenzel]

For St. Paul, Christ is the perfect image of God, and Adam represents the fallen image. Paul understands the human person as created “in Adam,” the fallen image of God. Paul further understood the Christian as having been redeemed through the saving work of Christ, which begins with an initial incorporation into Christ and an ongoing transformation towards his perfect image (see 2 Cor 3:18). Paul’s theology and pastoral ministry centers in helping Christians to understand and realize their new identity “in Christ” so they can act accordingly. Through their transformation according to the perfect image of God, they can be said to “have the mind of Christ” (1 Cor 2:16), which is inherently ordered toward building up the body of Christ through a love that participates in the pattern of redemptive service exemplified by him.

Paul’s vision of the Christian life is located within the “eschatological tension” between our initial incorporation into Christ and the completion of God’s work in us through our bodily resurrection at the end of time. Paul considers his former life—and all else—as loss or rubbish in comparison to being “in Christ,” which inherently leads to striving to know him more intimately through participation in his mission, and in his sacrificial pattern of life (see Phil 3:8).

For Paul—analogous to first century stoic virtue ethics—our ability to discern “what is good and acceptable and perfect” depends on our being “transformed by the renewal of [our] minds” (Rom 12:1-2). As the later Pauline writings further specify, this transformation entails “putting off” the vices of our fallen existence (see Col 3:5-9 and Eph 4:22) and “putting on” Christ (Rom 13:14). The Pauline tradition explains this transformation in terms of “putting off” the vices—as recognized in the popular stoic philosophy of the day—and appropriating the Christian virtues that begin with faith (Gal 5:6) and culminate in charity (1 Cor 13; Col 3:10-17 and Eph 4:23-24).

From these Pauline insights, we should note at least the following points. First, contemporary Catholics should similarly seek to ground their identity in Christ and deepen that by being transformed in virtue as perfected by charity. To this end, the study of, memorization of, and meditation upon Paul’s inspired writings is a proven means of identity formation, as is the case with the Gospels, for example. Second, we should be ready to relativize other aspects of our identity in comparison to our existence “in Christ.” Within a broader positive view of all creation as a gift of God, we can also identify with Paul’s use of the language of “loss” or “rubbish” regarding anything opposed to our identification with Christ.

Given recent decades in which it became common and even a point of honor for some of our most educated Catholics to proudly affirm their conservative identity, for example, I would argue that especially ideological and partisan affiliations should be kept at a critical distance. Such striving to identify with Christ should be uncontroversial for Christians. It is far easier said than done, however, because it entails casting aside attachments and loving to the point of death. In any case, St. Paul provides some of the richest New Testament resources to help us ground our identities in Christ, to relativize everything else in relation to that, and to recognize how our ability to discern truth depends upon our ongoing transformation according to his image.

2. Henri de Lubac, SJ on identity as a vir ecclesiasticus

The great twentieth-century Jesuit theologian Henri de Lubac also provides valuable resources that can also help us to form a properly Catholic sense of identity, namely his understanding of the vir ecclesiasticus, the man of the Church, or—more inclusively—the ecclesial person. I understand de Lubac’s recovery of the traditional notion of the vir ecclesiasticus within his life-long fascination with Pauline “mysticism,” as he called it. De Lubac gets this language of mysticism from the Greek mysterion in especially the letters to the Ephesians and Colossians. This is the mystery of life in Christ, which was also foundational to du Lubac’s unified Christocentric vision of theology. The French Jesuit not only began his voluminous publishing career with the topic of this Christian mysticism but maintained a lifelong interest in it.

[Henri de Lubac as Cardinal. Alethia.org]

De Lubac’s work not only influenced the Pauline sacramentalism of the Second Vatican Council about which I previously wrote. It also led to the famous no. 22 of the Council’s Gaudium et spes: Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World. This celebrated text—which St. John Paul II saw as a kind of hermeneutical lens for interpreting the council—affirmed that:

The truth is that only in the mystery of the incarnate Word does the mystery of man take on light. For Adam, the first man, was a figure of Him Who was to come, namely Christ the Lord. Christ, the final Adam, by the revelation of the mystery of the Father and His love, fully reveals man to man himself and makes his supreme calling clear.

As for St Paul, for de Lubac and the Second Vatican Council, it is Christ who reveals to us not only our deepest identity, but our supreme calling to carry out his work of redemptive love.

De Lubac’s understanding of the vir ecclesiasticus should also be understood within his understanding of the discipline of theology, which is rooted in his recovery of the traditional biblical hermeneutic. According to this traditional hermeneutic, Scripture has a literal meaning and a deeper spiritual one that we grasp with the help of the Spirit as we become more deeply conformed to the divine realities that the sacred texts mediate. The goal of the interpreter of Scripture, and of the theologian, is to gain “an ever deeper understanding of revelation” through the help of “the same Holy Spirit” who inspired the biblical texts (see Dei verbum, no. 5). For de Lubac, this theological task is a continuation of a biblical exegesis that honors the text but sees it as a sacramental reality putting us in touch with the divine mysteries. His theology is not only rooted in Scripture, but takes place within the broader Tradition, and within the ongoing life of the Church, aided by the discernment of the magisterium.

For de Lubac, living out this Christian mysticism of life “in Christ” also implied lovingly receiving the Church’s teaching, working as a theologian to renew the tradition and deepen our understanding of it, and enduring suffering to both explicate it and live it out. Given the way the magisterium of the Church has articulated the “integral and solidary humanism” of contemporary Catholic Social Doctrine after the interwar experience with fascism, and the experience of the Second World War, it would seem self-evident that followers of de Lubac and ressourcement theology would be exemplary “ecclesial persons” who receive this social doctrine and foster its realization in the world. Although this has too often not been the case in recent years, my hope is that this will increasingly be so as we strive to assist Pope Leo XIV in his service to the body of Christ.

De Lubac’s work can help us to not only deepen our appropriation of Paul’s christocentric spirituality by identifying as viri ecclesiastici, or ecclesial persons. It can also help us to identify with the deepening of this Christocentrism through the Second Vatican Council, and in the living out of Catholic Social Doctrine to bear the fruit of charity for the life of the world.1

3. Key Points on Identity and Discernment for Aquinas

St. Thomas Aquinas’s synthesis in the Summa Theologiae offers what is generally recognized as the most trusted medieval account of the creation, fall, redemptive healing, and perfection of the fallen image of God, all of which is effected by the grace mediated through the Paschal Mystery and poured out through the sacramental life of the Church. This medieval synthesis also provides a more philosophically robust explication of the Pauline understanding of being not only created in the image of God but transformed in Christ—and in virtue—so we can “discern what is good and acceptable and perfect” (Rom 12:2).

Identity

Presupposing the biblical accounts of our creation in the image of God, St. Thomas draws upon especially Aristotelian philosophy to provide a robust theological anthropology. For my present purposes I will highlight that this anthropology can complement those aspects of identity we appropriate from the biblical narratives and epistles. It can do so by providing—for example—an account of the powers and movements of the soul, which offers a foundation for his under-appreciated psychology, and his widely recognized exposition of virtue ethics. Given the Pauline understanding of our transformation in Christ and identity as a person of the Church, we can read the moral theology found in the Secunda Pars as providing a more philosophically robust and systematic exposition of how the fallen image of God is healed by grace, and conformed to Christ—by the growth in all the virtues—and aided by the gifts of the Holy Spirit to live out our missions in the world.

As a medieval theologian, Thomas would certainly presume that we should strive to be something like de Lubac’s understanding of the vir ecclesiasticus. As such, I think he would similarly take the fundamental orientations of contemporary Catholic Social Doctrine—with deep roots in an ecumenical council under the leadership of a Pope—as something to be received in faith. If this is correct, then he would embrace the understanding of the common good we find in CSD as “the sum total of social conditions which allow people, either as groups or as individuals, to reach their fulfilment more fully and more easily.”2 In saying this, I think he would see it as something to be integrated with—not opposed to—what he wrote on the common good. I think he would also recognize the centrality of public institutions as emphasized by Pope Benedict XVI and the last Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences.

Thomas’s robust account of the harmony between faith and reason also helps us to identify as lovers and seekers of Veritas. As the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church puts it, this pursuit of truth puts us “in friendly dialogue with all sources of knowledge.”

Discernment

For trusted doctors of the Catholic faith like St. Thomas Aquinas, there is truth, including an objective moral order in the sense of what corresponds to God’s wisdom and eternal law. As a fundamental characteristic of being created in the image of God, this rational order is accessible to us through both the “light of our natural intellects” (the lumen ratio naturalis)—although with an admixture of error—and through “the light of faith” (the lumen fidei), aided by the gifts of the Holy Spirit.

Regarding the human ability to discern the truth, Aquinas has a robust epistemology. Drawing upon Aristotle and other resources, he offers an account of how the human intellect is naturally oriented to the truth in both speculative and practical matters. The intellect is open to all truth, natural and supernatural, and can be given gracious assistance to see what is intrinsically intelligible. For Thomas, the explanation for why the intellect fails to attain the truth centers in the deleterious influence of the disordered passions in fallen humans, namely the unmoderated and thus unreasonable desire for goods or fears of evils. To the extent that our passions are virtuously shaped to conform to the order of reason, they not only allow the intellect to work unfettered, but assist it in seeing the truth.

Given the preceding discussion of identity, discernment, and the way passions can obstruct the intellect, I will briefly consider how I think many American Catholics—including some of the most intelligent and accomplished—have been hindered in their ability to understand the integral and solidary Christian humanism of Catholic Social Doctrine, and the discernment of the Papal magisterium regarding the signs of the times. In brief, I think many Catholics have been persuaded—at least partially through a long term and massive campaign of persuasion—to identify as conservative, and to be moved especially by the passions of fear and anger in response to the cultural left. This deliberate propagation of such conservative identities, however, and the corresponding manipulation of these passions have obstructed many Catholics from understanding how they should respond to one of the most pivotal times in human history. Because, however, even the briefest attempt to broach this complex and delicate matter merits at least a post in itself, I have put that in a post called Identity and Discernment (2 of 2): Culture Wars as Obstacle to Understanding CSD and the Signs of the Times, which will be published tomorrow.

4. Cultivating Our Christian Identity as Social Catholics

Since an ongoing theme of this substack has been to look to past social Catholics for inspiration, I will simply recall some of them here. This list includes the brilliant Cuban-American Fr. Félix Varela (1788–1853), the prescient Dominican Jean-Baptiste Henri-Dominique Lacordaire (1802-61), Bishop Wilhelm E. von Ketteler (1811-77), Blessed Giuseppe Toniolo (1845-1918), Stanislao Medolago Albani (1851-1921), Maurice Blondel (1861-1949), Msgr. John A. Ryan (1869-1945), Fr. Luigi Sturzo (1871-1959), Jacques Maritain (1882-1973), Yves Simon (1903-61), Robert Schuman (1886-1963), Fr. Ted Hesburgh (1917-2015), Pope John Paul II (1920-2005), Pope Benedict XVI (1927-2022), Pope Francis (1936-2025), and Pope Leo XIV (1955). There are many more such social Catholics that I hope to introduce.

To the extent we learn to identify with them, we will be living in Christ as viri ecclesiastici, as those guided by Veritas in our practical action, as social Catholics, and as those who can once again bring hope and healing to the human family.

Conclusion: Identity and Discernment

A major goal of this post has been to illustrate how some resources from the heart of the Catholic tradition can help us to root our identities more deeply in Christ our exemplar, and within his body the Church. My focus on identity formation was ordered toward fostering our ability to receive the social doctrine of the Church more fully, and to live it out through a response to the signs of the times that is informed by that doctrine and the discernment of the magisterium.

In part 2 of my discussion of identity and discernment, I will offer a sketch of how I think many intelligent and committed American Catholics have been diverted from the actual social doctrine of the Church to identify too closely with, and participate in, the conservative side of the culture wars.

For a more recent discussion of the vir ecclesiasticus, see Robert Imbelli’s foreword to a collection of lectures by Avery Cardinal Dulles, SJ. Imbelli describes how this was “[o]ne of the most heart-felt accolades the early fathers could bestow on a theologian.” He attributes it to Dulles because “his whole theological and priestly existence has been in service of the Church, dwelling in its midst, nourished by its tradition, seeking to extend that life-giving tradition to meet the questions and challenges of our time.” As such, he praises Dulles for receiving the teaching of the Second Vatican Council, and responding to the signs of the times.

As Bradley Lewis has shown, this understanding was not novel to John XXIII, but traces back through the moral manuals since Leo XIII’s Rerum novarum: On Capital and Labor.