Remembering Cesar Chavez for Our Times

The Social Catholic Roots of a Mexican-American Champion of Human Dignity

Reminder: readers can view the following post, and dozens of other ones, at the Social Catholicism and a Better Kind of Politics website.

In this post, I will briefly introduce the life and work of the esteemed labor leader Cesar Chavez (1927-1993). Following the same rationale as in the many posts I have published on other social Catholics who have preceded us, my hope is that Chavez can be another source of enlightenment, edification, and inspiration for those of us seeking to bring hope and healing to a world at risk of a dystopian future.

[Cover image of biography of Chavez]

On His Contemporary Importance for Hispanics, and for Everyone

The example of Cesar Chavez is particularly timely as he is best known for his work in defending the human dignity of especially—but not exclusively—Latin American immigrants who were suffering oppression. The human dignity of immigrants in the United States needs new champions today because they are being subject to a brutal campaign of demonization, propaganda, and apprehension and arrest by forces who are often masked and don’t identify themselves. These immigrants—even some with citizenship or at least the legal right to reside in the United States—are also being subject to deportation without due process. Some are even being sent to foreign prisons or camps outside the reach of justice, even in war-torn South Sudan with no foreseeable path to return. These frightening developments concern not just people of dark complexion, however, because even a cursory familiarity with history shows us that if one group can be scapegoated and oppressed by the government and denied due process of law, then none of us are safe. For this reason, the story of Cesar Chavez should be of interest not only to Hispanics or non-Caucasians, but to everyone.

My Particular Focus

Although there is much to say about Chavez (the Wikipedia entry on him is 51 pages), I will provide a very thin sketch that focuses on the Catholic side of the story that is often overlooked or downplayed by those who don’t realize that living the authentic Catholic faith entails being agents for justice, reconciliation, and peace in the world. I will also include trailers for a movie on Chavez that can be viewed online, currently at Amazon Prime. For those who have access to PBS Passport, there is also a documentary on his life and work in the American Masters series. Perhaps surprising to some, the PBS website includes a story on the Catholic inspiration for Chavez’s work for social justice, upon which I will draw below.

Background and Formation for Social Catholicism

As can be seen in my introductory posts on other social Catholics, I have a particular interest in the experiences that form Catholics like Cesar Chavez to become tireless defenders of the human dignity of the most vulnerable. This interest in the formation that enables Catholics to appreciate and live the authentic Social Doctrine of the Church1 traces to my two decades of work in seminary formation, preparing men for priestly ministry in the Church.2

Cesario Estrada Chavez was born in Yuma, Arizona in 1927 to a second generation Mexican-American family who spoke Spanish at home.3 He was raised as a Catholic by a devout mother.

[Cesar and his sister dressed for First Holy Communion. Courtesy of Cesar Chavez Foundation]

After as business setback for his father in the mid 1920s, Chavez’s family moved into the home of his paternal grandmother. Where he attended school, Spanish was forbidden and he was expected anglicize his name from Cesario to Cesar. After his grandmother died in 1937, in the midst of the Great Depression, the house was auctioned off for unpaid property taxes in 1939.

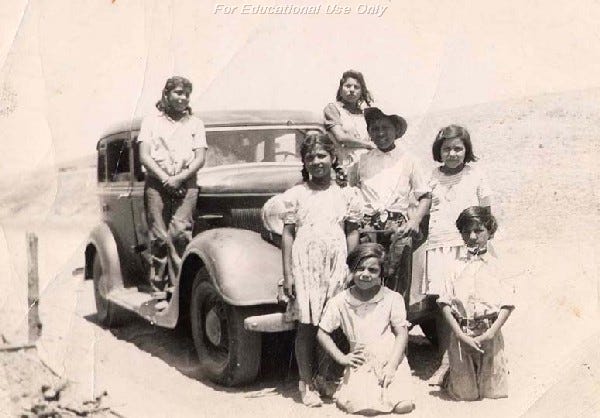

[The Chavez Children and the family car. Courtesy of Cesar Chavez Foundation]

The family then moved to California to find employment in agriculture, first as avocado pickers in Oxnard, and later living in a garage in the impoverished Mexican district of San Jose. While young, the Chavez family moved frequently and Cesar faced various forms of prejudice, including being ridiculed for his poverty. Upon completing junior high school in 1942, he became a full-time farm laborer before serving two years in the Navy (1944-1946) after which he returned to work in the fields.

[Chavez in his U.S. Navy uniform. Courtesy of Cesar Chavez Foundation]

By 1947, Chavez had joined the National Farm Labor Union (NFLU), and had begun picketing cotton fields for them. In that year, he also led a “caravan” of workers marching around the perimeter of the DiGiorgio grape property. By 1948, Chavez was married to Helen Fabela, and by 1949 the family settled in the Sal Si Puedes—literally, leave if you can—section of San Jose. Over the next three years Chavez alternated between work in the fields and as a lumber handler.

A decisive development for Chavez came in 1951, when he became friends with the social justice advocates Fred Ross and Fr. Donald McDonnell who were working to organize the Mexican-American community through the Community Service Organization (CSO).

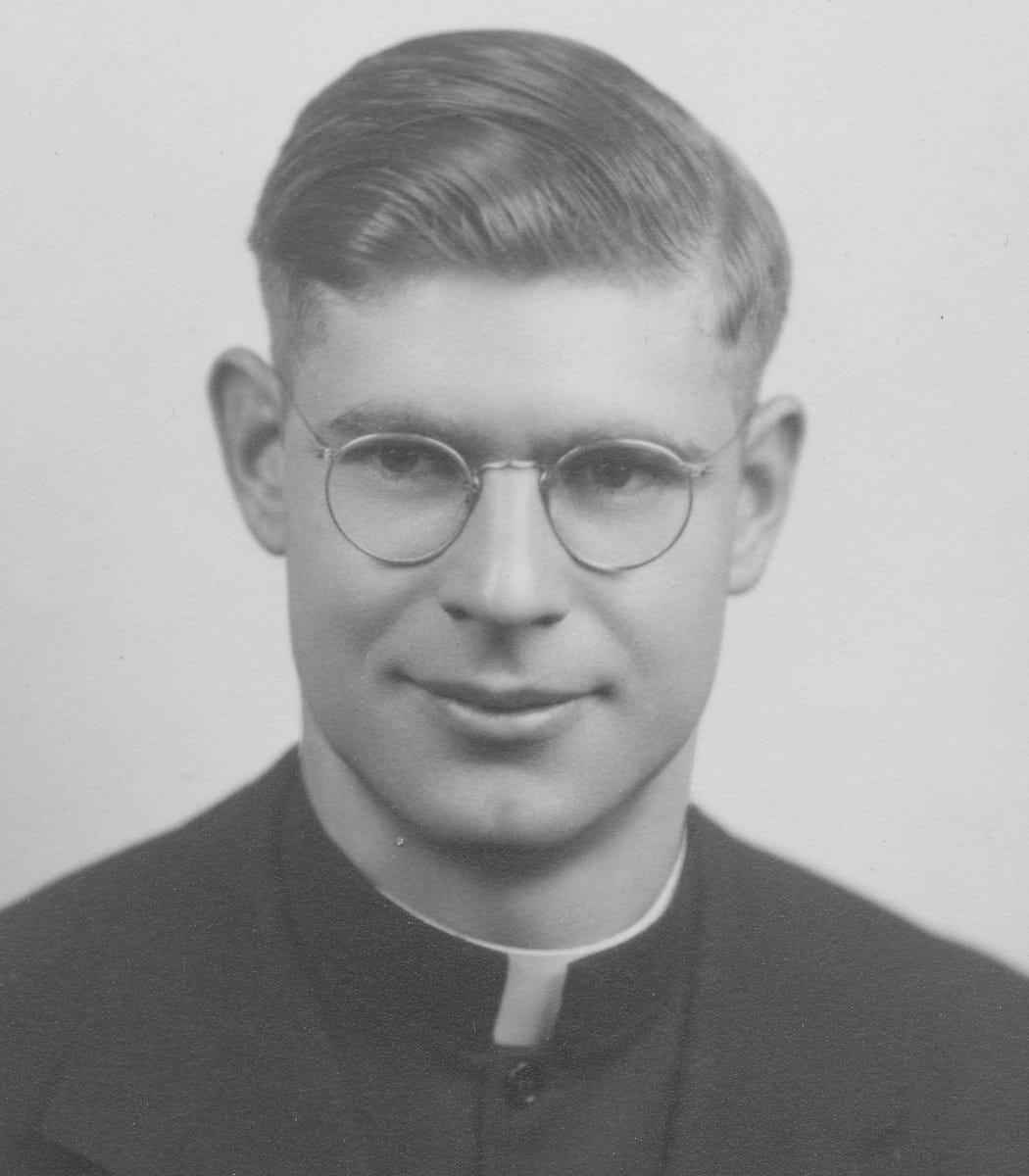

[Chavez mentor and friend Fr. Donald McDonnell]

The Catholic Roots of Chavez’s Work

Building upon his childhood faith, Chavez’s growing friendship with Fr. Donald McDonnell was deeply formative for him, especially regarding Catholic Social Doctrine. According to his son Paul F. Chavez: “My dad and Father McDonnell were both in their early- to mid-20s, and they became close friends. ‘I learned quite a bit from him,” my dad said, and it led to a lot of things.”4

At first, Chavez did chores to assist the priest—carpentry work, cleaning and painting. He drove Father McDonnell to perform mass at nearby camps for imported bracero farm laborers and for prisoners at the county jail. In turn, Father McDonnell introduced Chavez to the social justice teachings of the Catholic Church and to works on spirituality and human rights, including the writings of St. Francis of Assisi and M.K. Gandhi, biographies of labor leaders Eugene Debs and John L. Lewis, and classics of political philosophy by Machiavelli and de Tocqueville. It started out with “long talks about farm workers,” Chavez recalled. “I knew a lot about the work, but I didn’t know anything about economics, and I learned quite a bit from him. He had a picture of a worker’s shanty and a picture of a grower’s mansion; a picture of a labor camp and a picture of a high-priced building in San Francisco owned by the same grower. When things were pointed out to me, I began to see. Later I went with him a couple of times [from San Jose] to some [farm worker] strikes near Tracy and Stockton.”

This citation merits careful attention as it illustrates how Fr. McDonnell formed Chavez for the lay apostolate that follows from modern Catholic Social Doctrine and the Second Vatican Council. We can see from this citation that McDonnell rightly saw CSD as following from his sacramental ministry as we also saw in Msgr. Reynold Hillenbrand of Chicago and those he formed. Chavez also engaged in a wide range of ongoing study that included not only spirituality, but also the writings of labor leaders, social reformers, political philosophers, economists, and those of other faiths such as Gandhi.

Chavez continued:

“And then we did a lot of reading,” starting with Papal Encyclicals such as Rerum Novarum (Latin for Of New Things) by Pope Leo XIII in 1891, on the right of workers to organize, “and having the case for attaining social justice explained” by the priest. A biography of St. Francis [that] Father McDonnell had Chavez read mentioned “Gandhi and others who practiced nonviolence,” the farm labor leader recalled. “That was a theme that struck a very responsive chord, probably because of the foundation laid by my mother. So the next thing I read after St. Francis was the Louis Fischer biography of Gandhi,” which is still in his carefully preserved office/library at the National Chavez Center at La Paz in Keene, California.

Fr. McDonnell therefore set the middle-school educated Chavez on the path to become well-informed in a wide-range of subjects pertaining to the immense field of social justice. The recollection of McDonnell’s legacy notes how he had asked his bishop, early in his ministry:

to be relieved of parish duties and serve, along with a handful of other priests, as “priests to the poor” in what became known as the Spanish Mission Band throughout the 13-county Northern California Catholic Diocese, aiding farm workers and other poor Spanish-speaking Catholics. Father McDonnell’s base was Sal Si Puedes in East San Jose.

Arturo S. Rodriguez who was Chavez’s successor at the United Farmworker’s Union also understood the deepest motivations of his work. He said:

“Cesar Chavez tried to live the gospels and the social teachings of his Catholic faith every day, but his career dedicated to service to others all began with the lessons he learned early in life from his parish priest in East San Jose, Father McDonnell” … “Father McDonnell embodied those Catholic teachings and he profoundly impacted Cesar and so many others.”

My hope and prayer is that a new generation of American clergy will include many men like Fr. McDonnell, Msgr. George Higgins, Msgr. John A. Ryan, Bishop Wilhelm E. von Ketteler, and many others who recognize and live the authentic social doctrine of the Church. By the choice of his name and various exhortations, Pope Leo XIV is calling upon all Catholics to rediscover what its advocates ironically call “the Church’s best kept secret.”

[Chavez (Center) with Msgr. George Higgins (right) and an unidentified bishop]

PBS on Chavez

The introductory article to the PBS documentary on Chavez makes clear not only his great accomplishments, but also the Catholic inspiration underlying his work.

It begins with the assertion that “There is no question that Cesar Chavez is the most recognizable historical figure in the history of Latinos in the United States.” The piece proceeds to summarize his many accomplishments, but also emphasizes that “writers and historians have missed a crucial element of this leadership. They have ignored the deep religiosity and spirituality of Chavez. He was a brilliant organizer, but he was heavily motivated … because of his faith—his Catholic faith.”

It emphasizes that “Chavez believed in the power of his Catholic faith” and he saw his salvation is inseparable from his participation in “the struggle for social justice.”

His Catholicism inspired him to do good for others. He said: “I think there are three elements to my faith. It’s God, myself, and my brother. I’m traditional. I’m Catholic traditional. I go to Church regularly and faithfully . . . But besides that, I also have what I consider as a renewal religion. I go out and do things. That’s what I think is a real faith, and that’s what I think Christ really taught us: to go do something. We can look at His sermon [Sermon on the Mount] and it’s very plain what He wants us to do: clothe the naked, feed the hungry and give water to the thirsty. It’s very simple stuff and that’s what we’ve got to do.”

The article goes on to discuss Chavez’s struggle to defend the human dignity of not just farmworkers but of others who faced inhuman treatment. Thus, he was in the forefront of speaking up to defend the human dignity of homosexuals, which raised the ire of conservatives, but is easily reconcilable with the Catholic faith since everyone is created in the image of God and deserves to be treated with respect and the friendship of charity.

Of this he stated: “We must never forget that the human element is the most important thing we have—if we get away from this, we are certain to fail.” Human dignity was especially important for the poor who received no such treatment. Of the poor, Chavez added: “It is more than a union (UFW) as we know it today that we have to build. It is movement of the poor . . . We know that our cause is just, that history is a story of social revolution and that the poor should inherit the land.”

His Christian faith also made Chavez unhesitant before suffering, as in his fasting, and his offering of his life as a gift. He said:

“When we are really honest with ourselves, we must admit that our lives are all that really belong to us,” he confessed. “So it is how we use our lives that determines what kind of men we are. It is my deepest belief that only by giving our lives do we find life. I am convinced that the truest act of courage, the strongest act of manliness is to sacrifice ourselves for others in a totally nonviolent struggle for justice.”

The emphases of Cesar Chavez on non-violent struggle and willingness to suffer for justice are not to be missed as we consider what we might take from his example. I include below some trailers for the movie on his life.

Movie Trailers

To view the following trailers, click on the white arrow in the lower left corner, not the red one in the center.

By using the language of “Catholic Social Doctrine” I follow the example of Popes St. John Paul II and Benedict XVI, who preferred this to “Catholic Social Teaching” to emphasize that it was an integral—even if neglected—part of the deposit of faith. That is, Catholic doctrine to be received by all the faithful.

I am very attentive to the notion of formation for various reasons, starting with my background in Pauline theology—where it is a major focus—and because of my work in Thomistic virtue ethics. Formation for priestly ministry is also the purpose of seminaries, where address not only intellectual training, but also seek to form character regarding spiritual practices, human virtues, and configuration to Christ for pastoral ministry. I’m especially alert to the formation required to understand and live out Catholic Social Doctrine in especially American culture because I have witnessed the significant obstacles that especially native born American seminarians have in appreciating it, which is integral to receiving the teaching of the Second Vatican Council. The formation of clergy to receive—and become advocates for—Catholic social doctrine remains a driving motivation for me for many reasons. These include the fact that the clergy are integral to the renewal of the Church, and that I think the human family faces a bleak future unless the Catholic Church better manifests her authentic nature as salt and light in the world, and as an efficacious sign—that is, a sacrament—of unity among the human family and with God.

In this section, I begin by drawing primarily upon the Wiki entry on Cesar Chavez https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cesar_Chavez.

In this section I draw extensively from remarks from the funeral of Fr. McDonnell. http://www.cacatholic.org/index.php/about/bishops-of-california/331-rest-in-peace-rev-donald-charles-mcdonnell.