The Father of Modern Catholic Social Teaching

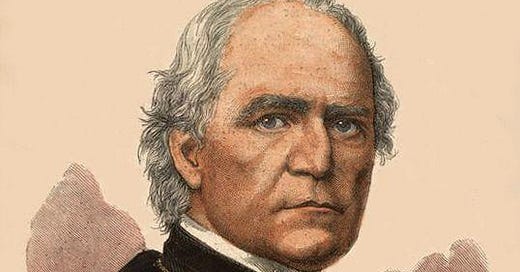

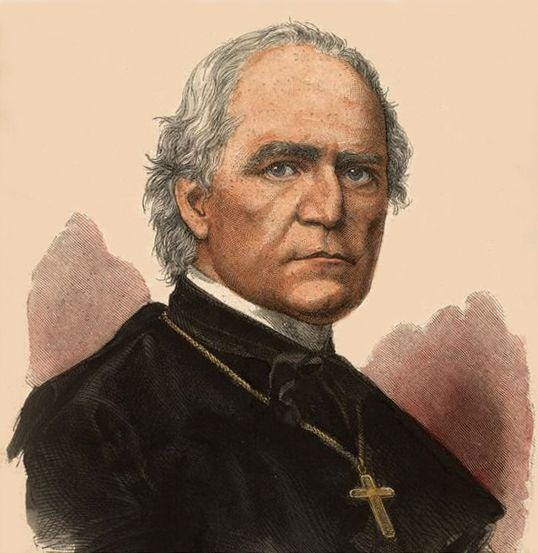

Bishop Wilhelm Emmanuel von Ketteler (1811-1877)

Before getting to the primary subject matter of this post, namely some of the key contributions of Bishop Wilhelm E. von Ketteler to the foundations of modern Catholic Social Teaching (CST)—I will provide some brief remarks about my initial plans for this substack.

Initial Plans: Social Catholicism and a Better Kind of Politics

Because Catholic Social Doctrine (CSD) considers the ethical dimensions of the entire social, political, economic, legal, and cultural realms, the scope of potential topics to be explored in this substack is vast. I will engage them under the aspect of how a retrieval of our social tradition can bring contemporary Catholics into collaboration to address the unprecedented set of challenges facing the human family today.

Because my new two-volume edited collection Social Catholicism for the 21st Century? is ordered toward the same goal as this substack, the initial posts will draw upon that work to introduce and complement the conversation in the collection. I will begin with reference to some of the initial essays in Volume 1, which is subtitled, Historical Perspectives and Constitutional Democracy in Peril (hereafter Volume 1). My initial priority is on establishing the foundational orientation of the modern Catholic social tradition, and on how the radical antiliberalism and postliberalism advanced especially by influential American Catholics reflects a radical break from that tradition, with potentially grave implications for the Church, the human family, and the planet.

As someone whose work in moral theology has been deeply influenced by the mid-century ressourcement or return to the sources movement, and especially a return to the Scriptures, I will occasionally include posts to manifest how the authentic social doctrine of the Church reflects an organic development of the deepest wellsprings of the faith under the wise discernment of the magisterium. This will serve as an ongoing reminder that Christianity is fundamentally a way of love, and not properly a speculative exercise, an apologetics, or a way of helping to win the culture wars. This return to the sources will also remind us that there is no love without justice, and that the Church has learned much about justice and living the life of charity in the modern world through the development of modern Catholic Social Teaching.

I turn now to my first post that draws upon the new collection.

Ketteler as Father of Modern Catholic Social Teaching

Bishop Wilhelm E. von Ketteler (1811-1877) is widely regarded as the father of modern Catholic Social Teaching (CST) as his exemplary work inspired subsequent generations of social Catholics and the corresponding tradition of papal social encyclicals, apostolic exhortations, and other written instruments of CST. After decades of largely ineffective Catholic responses to the challenges of the Industrial Revolution, his life and work marked a decisive turn toward a better way, one more consistent with what the Matthean Jesus spoke of as a “hunger and thirst for righteousness/justice” (Mt 5:6) and the love of God and neighbor (Mt 22:37-9).

In the aforementioned Volume 1, Dr. Martin O’Malley offers an erudite introduction to Ketteler’s life and work.

Image from Wikipedia Commons

The abstract to O’Malley’s contribution to the collection reads as follows:

This article examines Bishop Wilhelm Emmanuel von Ketteler’s biography, published works, and correspondence to demonstrate his relevance for CST in five points: First, Ketteler’s primary identity and loyalty was uncompromisingly Christian, rooted in Thomistic natural law, and thoroughly consistent with the church’s scriptural, theological, and ecclesiological commitments. Second, Ketteler’s legal education and experience informed his social writings. He respected and often incorporated secular and Protestant intellectual insights, including especially the “historical school” of jurisprudence—a branch of German Romanticism. Third, Ketteler’s dignitarian defense of individual human persons is consistent with contemporary discourses of human dignity and human rights. Fourth, Ketteler’s practical reasoning was ordered towards a theologically informed conception of human dignity and the common good. He sought prudential paths, which he called corduroy roads, to deal with this period’s social challenges. And fifth, Ketteler’s resourceful participation with representational forms of government demonstrates the rich potential for the church in public life where religious freedom is constitutionally protected. His social action took place in a context of an increasingly secular public discourse where Roman Catholics were a minority in the national structure formed in 1870 Germany. Ketteler confronted threats from the political left attempting to privatize religion and from the right that tried to nationalize church activities. He identified religion as politically essential while respecting structurally independent public spheres for both church and state.

For our present purposes, this abstract illustrates several themes that are foundational for understanding not only modern CST, but also the lived social Catholicism that incarnates it. In what follows, I will remark briefly on these five points and on their contemporary relevance. The reader is referred to O’Malley’s article and the broader collection for a far richer discussion.

O’Malley’s first point is of great contemporary relevance, namely that “Ketteler’s primary identity and loyalty was uncompromisingly Christian, rooted in Thomistic natural law, and thoroughly consistent with the church’s scriptural, theological, and ecclesiological commitments.” The relevance of this point concerns the contemporary disconnect between CST —precisely as it has developed since Ketteler through the discernment of the magisterium—and what has come to be understood as “orthodox” or “conservative” Catholicism, especially in the United States.

As someone who strives to be authentically Christian and Catholic, and who has worked out of the scriptural, Thomistic and ressourcement traditions in communion with the Catholic magisterium, I am fully convinced that contemporary Catholic Social Doctrine—as understood by the magisterium through Pope Francis—can be robustly embraced by self-identified “orthodox” Catholics as something that follows from the deepest wellsprings of our Tradition. On the other hand, I think those Catholics focused on social ethics would do well to manifest the deep grounding of this field in our doctrinal tradition, starting from Scripture as Ketteler does and including the Thomistic tradition.

I refer the reader to my contributions in Social Catholicism for the 21st Century? and some related works for further discussion.1 In these works, especially the introduction to Volume 1, I engage with what I call postliberal ressourcement Thomists who influence much of the “institutional infrastructure” of the Church in the United States. I argue that those who appreciate these traditions, as I do, can and should robustly embrace our social tradition and join in the efforts to preserve and renew constitutional democracies at home and abroad.

O’Malley’s second point is that “Ketteler’s legal education and experience informed his social writings. He respected and often incorporated secular and Protestant intellectual insights, including especially the “historical school” of jurisprudence—a branch of German Romanticism.” This reference to Ketteler’s legal education and experience indicates two essential foundations for social Catholicism, namely study of the disciplines relevant to social reform and practical experience. His incorporation of “secular and Protestant intellectual insights,” moreover, is an early example of what nos. 76-78 of the 2004 Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church describe as “a friendly dialogue with all branches of knowledge.” Such intellectual openness is another distinguishing mark of social Catholicism, and Catholic thought in general. It also implies an openness to dialogue with a range of interlocutors and collaborators in work for the common good.

The third point is that “Ketteler’s dignitarian defense of individual human persons is consistent with contemporary discourses of human dignity and human rights.” With his sound grounding in the biblical and theological traditions in dialogue with contemporary social challenges, Ketteler rightly recognizes that the Industrial Revolution of his day gave rise to various social conditions that offended human dignity and violated human rights. The tradition following his example eventually develops into the robust Christian humanism of the postwar era, which focuses on upholding human dignity through the articulation and defense of human rights.

O’Malley’s fourth point concerns how “Ketteler’s practical reasoning was ordered towards a theologically informed conception of human dignity and the common good. He sought prudential paths, which he called corduroy roads, to deal with this period’s social challenges.” With its focus on fostering the common good consistent with the dignity of human persons, Ketteler’s social Catholicism—and the subsequent tradition—has a properly practical focus corresponding to the Aristotelian and Thomistic understanding of practical reason.

Such reasoning seeks prudential means to achieve ends or goals, which are goods that participate in the common good; it therefore corresponds to the requirements of the political process in democratic polities. This fundamentally practical perspective can be—and has been—overlooked or distorted by Catholics who think primarily in terms of metaphysics, which for Aristotle and Aquinas concerns a different order of reason. Following this path tends toward the conclusion that Catholicism and constitutional democracy are irreconcilable, a conclusion that departs from the discernment of the magisterium over several decades on a matter of grave import for the future.

O’Malley’s fifth point addresses how—building on the previous four that will come to characterize the modern Catholic social tradition—Ketteler exemplified a “resourceful participation with representational forms of government.” He was able to do so even “in a context of an increasingly secular public discourse where Roman Catholics were a minority.” Within a dynamic of rival ideological extremes that has characterized the historical context of modern CST, Ketteler “confronted threats from the political left attempting to privatize religion and from the right that tried to nationalize church activities.”

In a final note of ongoing contemporary relevance, O’Malley discusses how Ketteler “identified religion as politically essential while respecting structurally independent public spheres for both church and state.” His example of creative participation in emerging modern secular states to defend human dignity and foster human flourishing—while avoiding the ideological extremes on both the left and right—has characterized authentic CSD to the present day.

As I have argued in Social Catholicism for the 21st Century? and related works, however, American Catholics have increasingly departed from this tradition in recent decades. This departure traces to the culturally conservative alliance of American Catholics with Evangelical Protestants over issues starting with abortion. Now generations into this break, not only has the “integral and solidary humanism” of the modern Catholic Social Doctrine become unknown or unintelligible to most Catholics. Ketteler’s corresponding understanding of the way in which religion should be understood “as politically essential” has also been lost. For Ketteler, Catholics—deeply informed by our biblical and doctrinal traditions and motived by a hunger for justice and love of God and neighbor—should participate in the political process of emerging modern states in pursuit of the common good.

For some of the most influential contemporary American Catholic conservative intellectuals, however, the emphasis has evolved to arguing that “liberalism”—including constitutional democracy—has already failed. This alleged failure traces to the fundamental incompatibility between Catholicism and constitutional democracy.

From this it follows that a postliberal order should be sought based on the model of the long-discarded Catholic “integralism.” Such an order would reestablish the bond between Church and state so the higher spiritual power of the Church could draw upon the coercive power of the state to foster adherence to faith and morals. One might reasonably object, however, that the imposition of this integralism would violate a fundamental principle of justice, namely, the golden rule. In practical terms, such a postliberal order would have conservative Catholics working in alliance with Evangelical Protestant Christian Nationalists to support the Trumpian form of the Republican Party that would supposedly “win” the culture wars through state coercion according to the model of Victor Orbán’s “illiberal democracy.”

In my introduction to Volume 1, I argue at length that contemporary Catholics should make a decisive break from this agenda and embrace the actual Social Doctrine of the Church. As I explain there, this would have us working in solidarity to renew the institutions of our constitutional democracy so we can address a frightening set of challenges and build a future worthy of the human family.

In subsequent posts, I will introduce many of the other essays that make up this collection. If you find this substack useful, please tell your friends and colleagues about it.

Thanks for reading! Subscribe for free to receive new posts.

See especially my “Three Contemporary Alternatives to Social Catholicism” in Chicago Studies 61.2 (Spring/Summer 2023).