The Relevance of Louis Cardinal Billot, SJ (1846-1931)

Thomism and the Dangers of Anti-Modernism, Anti-liberalism and Integralism

In my most recent post, I introduced a contribution by Peter J. Bernardi, SJ to my new collection on Social Catholicism for the 21st Century? My post, and Bernardi’s essay, discussed the 1909 intervention by the seminal ressourcement thinker Maurice Blondel. His compelling but insufficiently successful intervention defended the French social Catholics of his day and criticized their integralist opponents, who supported the proto-fascist Action Française (AF) movement—under the intellectual direction of the agnostic Charles Maurras—in their efforts to restore an alliance between “throne and altar.”

Because influential contemporary Catholics are advocating a neo-integralist alliance with an increasingly illiberal right to enforce traditional Catholic morality through the coercive power of the state, Blondel’s warnings that this strategy was “lethal to the Christian spirit” and concerned “the whole future of Catholicism” merits careful consideration.

It might seem that the position of Blondel and the social Catholics was definitively vindicated in 1926, when Pope Pius XI condemned AF, largely due to concerns with its intellectual leadership by Charles Maurras. This was a highly controversial move, however, not only because it conflicted with the position of the leading intellectuals of the day like Blondel’s opponent Descoqs. There was also a dearth of intellectual support within the burgeoning Thomistic revival for Catholic participation in a secular constitutional state like Third French Republic.

The example of the lay Catholic philosopher and Thomist Jacques Maritain is instructive of the intellectual situation regarding Catholics and constitutional democracy. Although Maritain becomes celebrated after the Second World War for his work in reconciling Catholicism and Thomism with constitutional democracy, he had been a collaborator of Maurras and AF, and didn’t make a decisive break with them until this papal condemnation of AF. After the condemnation, however, and in collaboration with his former student Yves Simon, Maritain increasingly focused on forging the postwar Christian humanism that firmly aligns Catholicism and Catholic Social Doctrine with modern constitutional governance.

As I will discuss in forthcoming posts, however, their efforts to reconcile Catholicism, Thomism and modern constitutional states bore little fruit among Catholics until after the horrors of fascism had become more evident through the tragedies of the Second World War and the Holocaust.

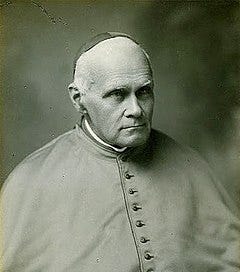

In this post, I will draw upon another timely historical study by Peter J. Bernardi, SJ that complements his contribution on Blondel. Whereas Blondel’s chief interlocutor was Pedro Descoqs, SJ, the last great representative of Suarezian scholasticism, this post will consider Louis Cardinal Billot, SJ, who was among the leading Thomists of his day and an ardent supporter of AF.

[Image from Wikipedia Commons]

Billot’s example merits careful consideration by contemporary Catholics, especially those of us who seek to work under the inspiration of St. Thomas Aquinas. Bernardi’s essay is entitled “Louis Cardinal Billot, S.J. (1846–1931): Thomist, Anti-Modernist, Integralist” and is available online through the Journal of Jesuit Studies, so what follows is an encouragement to read the whole thing. Bernardi’s abstract reads as follows:

Largely forgotten today, the French Jesuit Louis Billot was “the most important Thomistic speculative theologian of the late nineteenth century.” He taught generations of students at the Pontifical Gregorian University during the pontificates of Leo XIII and Pius X. His neo-Scholastic manuals remained influential until the Second Vatican Council. Having made a major contribution to the church’s anti-Modernist campaign, Billot was made a cardinal in 1910. He served on various Vatican congregations, including the Holy Office, during three pontificates. In the 1920s, Billot ran afoul of Pius XI for refusing to retract his support for the neo-monarchist, nationalist movement Action Française, led by the agnostic Charles Maurras, that had sought an alliance with French Catholics to defeat the anti-clerical Third Republic. Compelled to resign his cardinatial dignity, the only prelate in the twentieth century to incur this humiliation, Billot lived his last years in quiet retirement outside of Rome.

Bernardi essay considers Billot from three perspectives, as a Thomistic speculative theologian, as a leading figure in the Church’s anti-modernist efforts, and as a committed supporter of AF.

Thomist Speculative Theologian and Metaphysician

Billot’s work as a Thomistic speculative theologian put him in the forefront of efforts toward the renewal of Thomistic thought called for by Pope Leo XIII in his 1879 encyclical Aeterni Patris: On the Restoration of Christian Philosophy in Catholic Schools in the Spirit of the Angelic Doctor, St. Thomas Aquinas. In this capacity, he was undoubtably among the greatest thinkers of his generation, with his manuals widely diffused and republished up until the Second Vatican Council. He was a brilliant metaphysician who dominated the faculty at the Gregorian University and greatly influenced multiple Vatican congregations, which limited the extent to which his work could be challenged. Consistent with his focus on metaphysics, he showed little interest in historical concerns, textual sources—i.e., biblical exegesis—or insights gained from human experience. His works also manifest the “anti-liberal” mentality that had developed among many Catholics since the French Revolution, especially in the wake of Pius IX’s 1864 Syllabus of Errors, which condemned the proposition that “The Roman Pontiff can, and ought to, reconcile himself, and come to terms with progress, liberalism and modern civilization.” Bernardi cites Paul Duclos who writes that Billot “at times he forces the texts and deforms the thought of his adversaries” (590).

Intellectual Leader of Anti-Modern Program

Next, some brief remarks on Billot’s role in the Church’s anti-modernist efforts. As a leading advisor to Pope Pius X and member of the Holy Office, Billot is widely considered to have been a significant participant in the early 20th century anti-modernist interventions of Pope Pius X. Although Pius X was revered for his piety and virtue, he strongly resisted being elected to the See of Peter and was the last Pope until Francis to have not earned a doctorate. Scholarship detects Billot’s influence on the preparation of the two 1907 anti-modernist documents issued by Pius X. The first of these was the decree Lamentabili sane exitu, which was directed primarily against the exegetical, historical, and dogmatic writings of Alfred Loisy and his collaborators. The second was the more comprehensive anti-modernist encyclical Pascendi Dominici gregis.

Although Bernardi leaves it unmentioned in this article, adherence to these anti-modernist interventions was enforced by an unofficial group of censors organized by Monsignor Umberto Benigni, the Sodalitium Pianum (Fellowship of Pius). Bernardi also identifies Billot as “one of the principal drafters” of the 1910 Anti-modernist Oath. The great Dominican theologian Marie-Dominique Chenu described Billot as an “authoritarian” (593) and saw him as the leading intellectual force behind the anti-modernist era in the Church (596, n. 43). Billot, for example, “also argued that refusal of the oath should be viewed as a ‘schismatic act,’” although the Holy Office tended to simply deny ecclesiastical positions to those who would not take the oath (597).

Ardent Supporter of Charles Maurras and AF

Finally, a few remarks on Billot’s ardent support for AF, which was discussed in sufficient depth in my previous post. In the later years of Pius X’s papacy, the anti-modernist campaign “grew more fearsome” and “shifted to the socio-political terrain.” This led to the situation in which “integralists” and censors accused those working for justice of “social modernism” (597), which echoed the situation to which Maurice Blondel responded in my previous post. Those guilty of this alleged heresy included, for example, Catholics following the teaching of Leo XIII’s social encyclical Rerum Novarum by defending the rights of workers to organize. Billot “extolled Maurras and AF as the best defense in France against liberalism and democracy” (600). Toward that end, Billot advanced “a certain type of Thomism that often became a sort of weapon [instrument de guerre] in the hands of ecclesiastical orthodoxy police” which fostered the collaboration of Catholics with AF (600). Billot also “played a significant role in protecting Maurras from public ecclesiastical sanction,” which might have otherwise followed from “Maurras’s more flagrant anti-Christian (and anti-Jewish) writings” (601). Billot continued to support Maurras under the conviction that “against liberalism and democracy, there was nothing better than Maurras” (604). So deep was this conviction for AF—and, less directly, against the social Catholic alternative—that Billot chose to resign as cardinal rather than support Pope Pius XI’s condemnation of AF, as discussed in detail by Bernardi.

Conclusion: The Contemporary Relevance of Billot’s Example

For those of us who have welcomed and participated in the recent renewal of Thomism, what lessons should we take from the example of onetime cardinal Louis Billot, SJ? I will list several concisely and pick up the discussion in subsequent posts.

The first lesson concerns the limitations of a primarily metaphysical and speculative perspective for understanding Catholic Social Doctrine, which requires attention to the historical experience of the Church and to properly practical philosophy ordered toward achieving practical goods that participate in the common good as the Church understands it. Put otherwise, we should learn—from the experience of Billot and the French integralists—the lesson of the urgency of working to reconcile Catholicism with constitutional democracy. A second lesson concerns the danger—in such a metaphysical, speculative and anti-liberal approach—of overlooking the most fundamental biblical and Christian priorities of justice, concern for the most vulnerable (the poor, the widow, the orphan, and the stranger), and the practical realities of loving our neighbors in the modern world.

A third lesson concerns the corresponding danger of aligning Catholics with not just the powerful but with fascists who employ the power of the state without regard to the rights that protect human dignity. A fourth concerns separating oneself from the long discernment of the magisterium regarding the Social Doctrine of the Church. Whereas Billot’s story illustrated one manifestation of such a stance, contemporary Catholics who may be on an analogous trajectory need to carefully consider whether they are on a path that leads away from the Church, from Christ, and therefore from Goodness, Truth, Unity and Beauty. A related and fifth lesson concerns the dangers of a radically anti-liberal stance, which I would argue are manifest from the anti-modernist era through the Second World War.

In my next post, I will further elucidate the disastrous consequences that followed from the anti-liberalism of the French Catholics of the interwar years, drawing upon the roughly contemporaneous account of the lay philosopher Yves Simon in his The Road to Vichy: 1918-1938.