Maurice Blondel's Defense of the Social Catholics Against the Integralists

Ressourcement Theology and Social Catholicism

In this post, I will introduce the contents of an essay entitled “Maurice Blondel’s Defense of Social Catholics and His Enduring Critique of Catholic Integralism,” by Peter J. Bernardi, SJ. This essay is included in Social Catholicism for the 21st Century? Volume 1 Historical Perspectives and Constitutional Democracy in Peril. It “…offers a case study of an incisive diagnosis of the mentalities of French Catholics who were deeply divided over what strategy to adopt to re-Christianize society in the early decades of the twentieth century.”

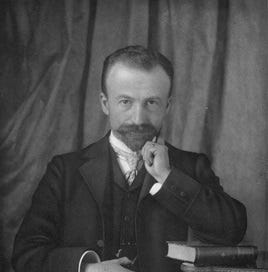

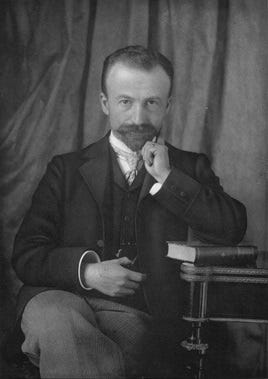

[Maurice Blondel Image from Creative Commons]

Blondel’s (1861-1949) intervention into the debate concerning the alternatives of social Catholicism and integralism is of great contemporary relevance for several reasons. These include the importance of his influence on the last century of Catholic thought,1 the fact that contemporary American Catholics are either largely unaware of—or hostile to—the social Catholicism that Blondel considers the proper mode for our socio-political engagement, and the fact that influential contemporary American Catholics are now promoting forms of the integralism that Blondel considers contrary to the authentic spirit of Christianity.

In what follows I first summarize Blondel’s rationale for defending the French social Catholics. I will then introduce his stern criticism of a form of integralism associated with the Action Française (AF) movement that a leading Catholic scholar had argued could be supported by Catholics.

Defending the Social Catholic Collaboration with Anti-Clerical Republicans

Bernardi explains how Maurice Blondel “defended the social Catholics of the nascent Semaine sociale organization who were open to collaboration with anti-clerical republicans to secure justice for the workers” (177). Following the example of the “study circles” that had arisen across Europe after the example of Bishop Wilhelm Emmanuel von Ketteler, these French social Catholics held study weeks—Semaines sociales—to understand both the social challenges of the day and the possible remedies for them. Given the persecution of the Church and ongoing tensions since the French Revolution, is not difficult to understand why collaboration with anti-clerical republicans to achieve justice for workers was controversial.

The approach of the Semaine sociale Catholics to political engagement can be described as participationist and reformist in relation to constitutional democracy, which is consistent with that of other social Catholics discussed in previous posts including Bishop von Ketteler, Fr. Felix Varela, and Msgr. John A. Ryan.

Blondel’s defense of these social Catholics was, however, focused less on their political participation than on what he considered to be the more important issues at stake. He understood these to concern “the entire future of Catholicism” (190), because he considered the integralist option of the Church employing the coercive power of the state as “lethal to the Christian spirit” (179). This grave assessment of the stakes explains why Blondel chose to intervene—at the height of the modernist crisis—under the pseudonym of Testis (Latin for witness), which reflected his belief that he was bearing witness to fundamental truths of the faith (180).

Blondel thought the debate turned on different approaches to epistemology, to ontology, and to the relation between the natural and supernatural orders. He termed “the ensemble of philosophical and theological positions to which he subscribed ‘integral realism’” (193). His epistemology or philosophy of knowledge was linked to that of human action, insisting that “actions are not simply the putting into practice of logically defined ideas…as if human beings were only pure intellects…” (183). His ontology—or philosophy of being—insisted that “reality is an interconnected whole in which no order of being is absolutely enclosed in itself” (191).

Blondel’s approach to the relation between the natural and supernatural orders rejected the tendency of his opponents to separate them, as if the supernatural could be thought of as an external overlay, like the icing added to the cake of the natural. He instead held that while the supernatural was “entirely gratuitous and absolutely transcendent,” it was also “supposed and presupposed” by the natural order. Put otherwise, they should be understood as a living compenetration.

For our purposes, Blondel’s understanding of these orders leads him to reject a conception of the socioeconomic order conceived in abstraction from the origin and destiny of the human person (193). This does not mean, however, that he thought the Church and state should be joined according to an integralist model that enabled the Church to employ the coercive power of the state to impose morality, as I will discuss below.

The following text by Bernardi links Blondel’s support for the collaborative model of the social Catholics to the key issue of the nature-grace relationship, and how this has shaped the teaching of the Second Vatican Council and the subsequent social doctrine of the Church.

…by their openness to collaborating with anti-clerical republicans on programs and legislation to bring about social justice, the Semaine sociale Catholics effectively appropriated Blondel’s non-dualist understanding of the nature-grace relationship. The Second Vatican Council will vindicate this understanding of the value of human efforts to promote a just social order in relationship to the Kingdom of God, which relationship is a consequence of the unitary destiny of the human person (193-4).

Bernardi cites Blondel to explain that the “social Catholics and the philosophers of action have done the most to show ‘the essential heterogeneity and real continuity of the two orders’ of the natural and the supernatural” (193). From this “real continuity of the two orders” (193), Blondel recognizes that the republican collaborators of the French social Catholics can rightly grasp something of the demands of justice and participate in efforts to address them. This does not mean, however, that he understands such collaboration to take place outside the movement of God’s supernatural grace. Instead, these social Catholics rightly recognize that grace can be at work from below and are attentive to the “stammerings, the complaints, [the] griefs that arise from the people” (194), a view reminiscent of the opening number of the Second Vatican Council’s Gaudium et spes: Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World.2

This insight that Catholics can collaborate with a broad range of others in the working for the common good, I would argue, is why Archbishop John Ireland’s evangelical strategy of “making America Catholic” by moving to the forefront of efforts to confront social challenges was effective, as I discussed in a previous post. It also explains why chapter 2 of the Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church presents the Church’s evangelical mission and Social Doctrine as intimately bound.

Although the intellectual debates can get complex, I would argue that these social Catholics were simply living out the charity that is the essential mark of authentic Christianity, which presupposes that we work against the injustices that offend the human dignity of our neighbors. Of course, these neighbors are considered broadly—as Jesus taught in the parable of the good Samaritan—to include those with whom we may disagree on matters we hold dear.

I will next turn to Bernardi’s discussion of Blondel’s criticism of the collaboration between Catholics and the integralism of his day.

Opposing the Collaboration with the Integralism of Action Française (AF)

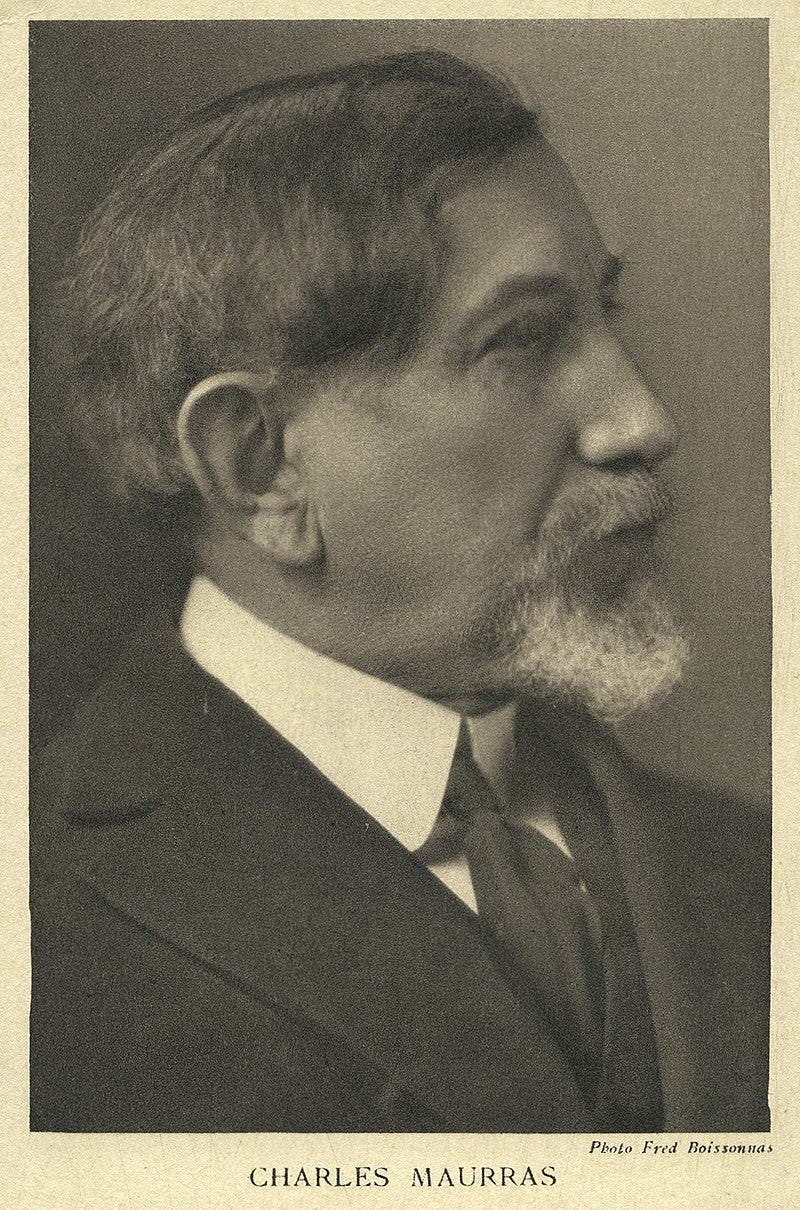

Bernardi discusses in some detail how Blondel “sharply criticized Catholic collaboration with the politico-cultural movement of Action Française (AF) that sought an integralist restoration of “altar and throne” to defeat the dominant secular liberalism…” (177). The intellectual leader of AF was the proto-fascist and anti-liberal Charles Maurras, a self-proclaimed “Romanist,” who was also a monarchist, a counter-(French) revolutionary, an anti-communist, an anti-Mason, an anti-Protestant and a nationalist. Maurras later supported the Vichy regime in France that collaborated with the Nazis during the Second World War. He has been an influential source of right-wing and far-right thought since the early twentieth century.

Maurras called himself “Roman” based on his understanding of the Roman Catholic Church as “…a rampart” and “historic bulwark of social order” (184), which he saw as necessary for the survival of civilization. Although baptized a Catholic as an infant, Maurras not only fell away from the faith but “expressed contempt for the spirit of the biblical prophets,” for Jesus in some early writings, and for Mary’s Magnificat (185). Because the social Catholics find warrant for their work for justice in the call of the prophets, in Jesus’ proclamation of good news to the poor, and in Mary’s praise of God for casting down the mighty and lifting up the lowly, it is clear that they have a quite different orientation than Charles Maurras and AF.

[Protofascist Charles Maurras]

Blondel’s criticism focused on the qualified endorsement for Catholic collaboration with AF offered by the prominent scholar Pedro Descoqs, SJ. This French Jesuit saw grounds for collaboration with AF precisely in Maurras’s understanding of the moral order which was seen as the natural order, and regarding which AF had a “blueprint [for social reconstruction] (184). For such reasons, “Descoqs opined that Maurras gave the impression of being ‘almost one of her [the Church’s] sons’” (185). Descoqs “defended Maurras’s capacity to arrive at the truths because the political and social order has its own autonomy” (186).

As outlined above and discussed at greater length by Bernardi, Blondel’s critique of Descoqs centers on their differing approaches to epistemology, to ontology and to the relationship between the natural and supernatural orders.

Blondel gave his “witness” for what he saw as essential to the Christian faith against the combination of Decoqs’s Suarezian scholasticism and Maurrassian integralism that would coerce people through state power into following the moral order. He saw this as reflecting “a pervasive and insidious ‘extrinsicist’ mentality, which he labelled “monophorist,” which literally means “one-way street” (190). Here the word extrinsicist included the implication that the faith—understood in a moralistically distorted way—could be something imposed upon people. This extrinsicist monophorism—or simply monophorism— was also, therefore, “Blondel’s term for a reigning clerical authoritarianism which on principle refused to recognize that grace could work from below” (193). This reductionist understanding of the workings of God’s grace explains why the Maurrassians mistakenly charged the social Catholics with “social modernism” for thinking that God’s grace can be at work in their anti-clerical republican collaborators.

Blondel saw this extrinsicist and authoritarian mentality as inclined to “boast of its orthodoxy” (190), and to present the Christian faith as “‘a law of fear and constraint, as an instrument of domination,’” tracing to the deficiencies of “‘manualist theology’” (193). This extrinsicism, moreover, tends to treat people as perpetual children, to demand from them a passive docility, and “to present Christianity not ‘as a liberation and an expansion for our being’ but ‘as a new subjection, as an oppression…’” (194).

Bernardi concludes this subsection as follows:

In the face of this radical “denaturing” of the “Good News,” Blondel poignantly asked: “Apart from the Catholic truth, is not the very meaning of the moral destiny and the human religious conscience misconstrued?”

Although the criticism Blondel offers is biting, and although the best of the scholastic tradition can be interpreted at the service of the richest streams of New Testament revelation, discerning readers will recognize the contemporary relevance of his message.

Conclusion

In this post, I have sketched some of the key points developed in Pete Bernardi’s essay on Maurice Blondel’s early twentieth century defense of the French social Catholics against the integralists. This debate is of urgent contemporary relevance to American Catholics because, on the one hand, the participationist and reformist model of social Catholicism has become almost unknown to us in recent decades as influential Catholics forged a political alliance with the Republican party around issues starting with opposition to abortion. On the other hand, some of today’s most influential Catholic academics are now advocating for a form of the integralism against which Blondel argued, while the Republican Party has become increasingly anti-democratic and authoritarian. This new discussion of Blondel’s intervention could not be more timely for Catholics in the United States as early voting is already underway in perhaps the most important election since the Civil War.

In future posts, I will continue to build upon the foundation laid in those published so far.

His importance begins with his seminal place in the 20th century ressourcement—or “back to the sources”—movement that included such giants of Catholic thought as Henri de Lubac SJ, Yves Congar OP, Jean Daniélou SJ, Marie-Dominique Chenu OP, Hans Urs von Balthasar, and Joseph Ratzinger. This movement was not only a primary influence on the Second Vatican Council. It has also informed the thought and action of the subsequent popes who have struggled to realize the Council’s promise, most notably St. John Paul II and Benedict XVI, but also Francis.

“1. The joys and the hopes, the griefs and the anxieties of the men of this age, especially those who are poor or in any way afflicted, these are the joys and hopes, the griefs and anxieties of the followers of Christ. Indeed, nothing genuinely human fails to raise an echo in their hearts. For theirs is a community composed of men. United in Christ, they are led by the Holy Spirit in their journey to the Kingdom of their Father and they have welcomed the news of salvation which is meant for every man. That is why this community realizes that it is truly linked with mankind and its history by the deepest of bonds.”