This post introduces “The Social Catholicism of Fr. Félix Varela (1788–1853)” by Peter Casarella of Duke University, which is included as chapter 2 in Social Catholicism for the 21st Century? Volume 1 Historical Perspectives and Constitutional Democracy in Peril.

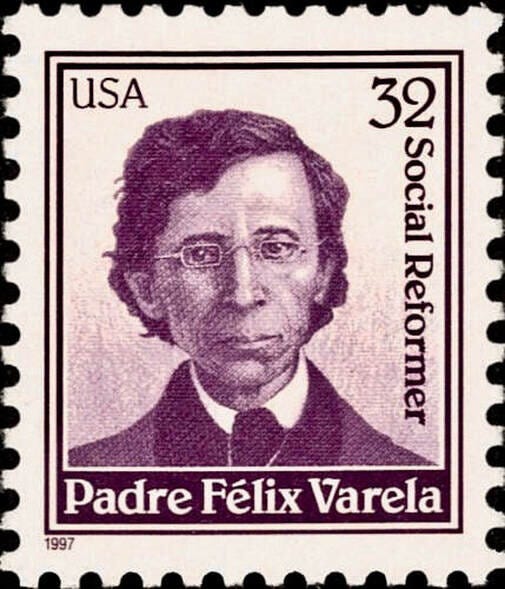

[Copyright United States Postal Service. All rights reserved.]

I will introduce Casarella’s article by citing heavily from it, without cluttering the text with page references.

“Félix Varela was born in Havana on November 20, 1788, but he spent his childhood in St. Augustine, Florida.” In 1811 he was ordained a priest and appointed “Professor of Philosophy in the Seminary of San Carlos and San Ambrosio of Havana.” In this capacity, “Varela was the leading [Cuban] educator, philosopher and patriot of his time, teaching philosophy, chemistry, physics, theology, and music.” He was also given a “chair in constitutional law while he was still in Cuba even though the latter had no formal training as a lawyer.” He is remembered today as the man who taught Cubans to think.

Varela’s advocacy for the independence of Spanish colonies in Latin America, for Cuban self-rule, and for the abolition of the slave trade resulted in his condemnation to death. He managed to escape to the United States in December of 1823, and to avoid an assassin sent in pursuit by the Spanish Crown. During his three decades of ministry as an exile in the United States, Varela brought “his vast erudition, extensive training in the history of philosophy, and familiarity with the Anglo-American theory of democratic constitutionalism to bear on the pastoral concerns of his flock and the shaping of an emerging civil society.”

Varela’s thinking about, and advocacy for, justice was from the perspective of one engaged in the struggle for it and reflects an indispensable component of social Catholicism. Casarella writes that he speaks prophetically about the various forms of social and political oppression as “idols to be destroyed.” Although Varela was among the most erudite men of his time, his learning was inseparable from his advocacy for justice based on his understanding that “the relationship between truth and virtue is mutually determinative.”

Fr. Varela’s political thought centers in a theology of “public spirit” which reflects an engagement with French scholars who understood L’esprit public in terms of public opinion. Varela’s theology of public spirit has a unique emphasis, centered on public discourse, which he equates “with advocacy for personal freedom, independence, democracy, and a rule of law while interrogating pressing social realities through a critique of ideologies.”

Casarella’s notes how this theology of public spirit that Varela employs in the service of social justice is still “essentially Thomistic.” Echoes of St. Thomas can be seen in Varela’s emphasis on the common good over personal goods, and in his general grounding in the virtue ethics of St. Thomas. Varela also anticipated something close to the understanding of subsidiarity in contemporary Catholic social thought. Although his social thought recognized the importance of love of country, he rejected what he saw as false forms of patriotism.

From the perspective of this substack which seeks to foster a new social Catholicism, I would reiterate the following points. First, Varella prefigures—decades before better-known advocates of social Catholicism like Bishop Wilhelm E. von Ketteler—the Gospel-inspired and well-informed advocacy for justice in evolving democratic societies that will characterize social Catholicism. During his pastoral visit to Cuba, Pope John Paul II affirmed Varela’s work for democracy, “judging it to be the political project best in keeping with human nature, while at the same time underscoring its demands.”

Second, Varela’s efforts to respond to new social and political questions through developments of the Thomistic tradition are a reminder that social Catholicism grew out of the mainstream of the Catholic tradition, although developed to meet evolving challenges. It is not something optional for leftists or those who do not care about our doctrinal tradition. In future posts, I will emphasize how our social tradition has deep roots in the Old Testament emphasis on justice, which is inseparable from a special concern for the vulnerable, namely the poor, the widow, the orphan, and the stranger / alien. Of course, these emphases from the Old Testament are not abolished in the New Testament but are fulfilled in the greater righteousness of the kingdom Jesus proclaims in his Sermon on the Mount (see especially Mt 5:17-20).

Third, Varela places considerable emphasis on critical engagement with ideologies, and I will return in this substack to the need for contemporary Catholics to do the same.1

A fourth point I would emphasize is that contemporary American Catholics—especially those who want to speak of holiness, virtue, and spirituality—should take note of Varela’s heroic courage in calling for social reforms. In particular, he spoke out boldly for independence from colonial oppression, for freedom at various levels, and for the end of slavery. He certainly had sufficient foresight to realize that this might cost him dearly, but that did not stop him. In my opinion, there are similarly grave threats to human dignity and the common good in our day, and the magisterium of the Church has been keen to highlight them in the social encyclicals. There has been a dearth, however, of Catholics with sufficient solicitude for the human family to speak out, and labor, for the needed remedies at a time when we have had the fragile democratic freedoms to do so. In this, Fr. Varela gives us the occasion for an ongoing examination of conscience.

This leads to a fourth lesson we might take from Varela, one relevant to an age during which there has been what I have welcomed as a considerable renewal of Catholic thought, especially in Thomistic and ressourcement traditions in which I was formed. I see this lesson in Varela’s example and his insistence that “the relationship between truth and virtue is mutually determinative.” If I understand him correctly, this mutual determination helps to illumine why he was not only distinguished by his broad learning, but by his emphasis on exercising his theology of public spirit in the pursuit of justice. In this, I am reading him in light of Aquinas’s understanding that charity—centered in acting for the good of the other—is the most noble of the virtues and what informs all truly virtuous acts, and that justice regarding the common good is the highest of the moral virtues.

My hope is that Varela’s example might inspire considerably greater attention to questions of what he calls “public spirit” among contemporary American Catholic scholars.

For an excellent new resource on ideology, see Jason Blakely’s new Lost in Ideology: Interpreting Modern Political Life (Newcastle: Agenda, 2024).