The Socio-Political Vision of Pope Francis

On the Nature and Importance of His Message for the Contemporary Church

Note: this newsletter is also available at the betterpolitics.substack website, which gives access to 57 previous posts.

With the rest of the Catholic world, I awoke Monday morning to the sad news that Pope Francis has passed on to his eternal reward. Word of his passing has been met by a continuing stream of praise from across traditions and cultures, which has focused on his characteristic love for the most vulnerable. In the midst of a world that seems to be racing toward a harsh break from the postwar era of democratic humanism that reflects significant affinities with Catholic Social Doctrine, the perennial and universal appeal of Pope Francis’s witness to the dignity of every human person provides an opportunity to consider his broader social vision.

Much like the “hard sayings” of Jesus, however, Francis’s social teaching—which is simply that of the Church—calls each of us to “repent” (Greek: metanoein, to repent, to change one’s mind or thinking) and to “turn” (Greek: epistrephó, to turn or return) and take up a way of life more consistent with the Gospel. It means changing our way of thinking in light of “the kingdom”—the realm where God’s rule is present—that is “breaking in” in the person, words and works of Jesus. In this kingdom, Jesus calls us to turn our lives from a worldly way of thinking that prioritizes saving our own lives, striving to be first of all, or to be great. This means turning to live our lives according to a way of thinking where we lay down our lives for our neighbors, and become servants of all.

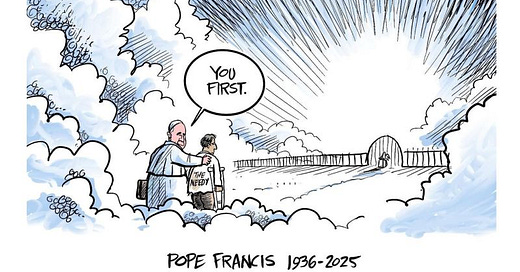

[Marshall Ramsey’s viral cartoon of Pope Francis Creators.com 2025]

In my opinion, Pope Francis’s social teachings and witness are arguably the most important part of his legacy for the Church and for the human family. The primary textual witnesses to Francis’s social teaching are certainly his two major social encyclicals Laudato si’: On Care for Our Common Home (2015) and Fratelli tutti: On Fraternity and Social Friendship (2020). His integral Christian humanism, solidarity, special care for the marginalized, concern for our common home on earth, and social friendship were manifest—moreover—throughout his writings, in his spoken words, and in his actions.

[OSV News illustration Joe Heller]

Pope Francis’s exemplification of the Church’s perennial social teachings, was not something novel, although it was shaped in response to the unique signs of our times. It was instead profoundly Catholic, and an organic development of our tradition. It was in evident harmony, therefore, with the Old Testament’s continual concern for not only justice (Hebrew: tsedaqah, or misphat for judgment), but for steadfast love and mercy (Hebrew: chesed). Fidelity to this ancient biblical ethic was shown continually by Pope Francis through his care for the most vulnerable, those on his beloved “peripheries.” In the Old Testament these were signified by the widow, the poor, the orphan, and the stranger. These foundations of biblical ethics, moreover, are not abrogated but fulfilled in Jesus, who not only preaches good news to the poor and liberty to captives, but also—through his sacrificial love—brings about a kind of reversal that, in God’s eschatological time, casts down the mighty from their thrones and lifts up the lowly.

Since so much has already been written and broadcast in memory of Pope Francis, I will focus below on providing brief introductions based on the abstracts to several contributions to my Social Catholicism for the Twenty First Century? As implied by the title, which notably includes a question mark, this collection seeks to foster a renewal of what Pope Francis calls “a better kind of politics.” As the question mark indicates, however, this will require that many Catholics turn their lives toward a living out of the Gospel that is informed by Catholic Social Doctrine, in response to a realistic grasp of “the signs of the times.” A good place to start is with an overview of the Social Vision of Pope Francis.

The Social Vision of Pope Francis

This socio-political vision is artfully sketched in an essay entitled “Reimagining the World from the Peripheries: The Social Vision of Pope Francis” by Clemens Sedmak of the University of Notre Dame. It is included in Social Catholicism for the Twenty First Century? Volume 2, New Hope for Ecclesial and Societal Renewal. Drawing upon the abstract, this essay “offers a reflection on the social vision of Pope Francis, which it understands as the kind of community he wants to see. It proceeds in two steps. The first introduces Pope Francis’ vision of Europe as an example of his political ethics.” The abstract continues that “For Francis, Europe is both part of his personal heritage and a political entity with a rich history. This rich history leads to a humane politics offering a vision of peace and hope that can be a gift to all of humanity.”

To appreciate this essay, it is essential to remember that postwar Europe was founded—after the tragic experiences of fascism and two World Wars—by primarily Christian democratic and social democratic parties. In this postwar re-founding of Europe, Catholic leaders informed by the Christian humanism of postwar Catholic social teaching were indispensible. In dialogue with Pope Pius XII, these leaders included Robert Schuman of France, Alcide De Gaspari of Italy, and Conrad Adenauer of (West) Germany. Their countries became parts of a postwar liberal order of constitutional democratic states that reflected the Western consensus for what can be called a Keynesian mixed-economy, or “embedded liberalism” in which a market economy was embedded within a strong state that provided the necessary “public goods” such as defense, education, infrastructure, regulation, and a social safety net. Such societies established the postwar international institutions that led to the 1948 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which they strove to implement. Despite the fact that this vision was only partially realized, it resulted in an unprecedented eight decades of relative peace and prosperity, that was in no small part a fruit of modern Catholic social doctrine in dialogue with those of good will.

The abstract continues: “In an age struggling with globalization” and the rise of a new illiberalism, “Europe is a test case to illustrate Francis’ social vision. To the extent that Europe recovers its vital soul, which traces to the Gospel, it can advance the dignity of the human person, justice, freedom and solidarity.” Here we see Pope Francis picking up on the efforts of Pope Benedict XVI to encourage contemporary Europeans to appreciate how their continent has been deeply shaped by its Christian roots, and should see Catholics as valuable allies in support of their most noble principles and aspirations.

“The second part [of the essay] discusses a central notion of Pope Francis’s pontificate, the idea of going out from self and going to the ‘peripheries.’” Although this language is usually presented as a personal call, for Francis, going out to the peripheries is also “what a Europe drawing upon its Christian soul will do, and what the Church will do anywhere she is in touch with her deepest sources of vitality.” I understand this as an affirmation of efforts of international solidarity that reflect the best of the postwar liberal order. “This section treats the fundamental commitment to the peripheries, the many kinds of them, and the way they shape the theological imagination.”

In a nutshell, Pope Francis is a strong supporter of the postwar liberal order of constitutional democratic states with embedded market economies that became the Western consensus after the Second World War. He sees this as aligning with the “better kind of politics” that follows from Catholic Social Doctrine, and perhaps unable to endure without it.

The Global Polycrisis and A Better Kind of Politics

In my extended introductory essay to Volume 1, Historical Perspectives and Constitutional Democracy in Peril, I begin by putting Pope Francis’s reading of the “signs of the times” in Fratelli tutti in dialogue with the insights of global thought leaders like Adam Tooze. The first part of this essay:

…highlights the need for careful discernment amidst a tumultuous era in which the postwar hopes for the human family and Church have been deeply disappointed, with the secular world failing to realize the postwar hopes for a more just and peaceful world, and with the Church failing to manifest her incarnation of the Gospel ministry of reconciliation, as a light to the nations, as an efficacious sign of unity, and a leaven in society. In the wake of these disappointments, we are faced with a series of interlocking and potentially existential challenges for the human family that has been described as the polycrisis, which coincide with an unprecedented degree of contestation within the Church over the reform agenda of Pope Francis.

Returning to the abstract of my introductory essay:

The second section argues that such discernment should lead to a decisive choice to live out a new social Catholicism—corresponding to what Pope Francis calls “a better kind of politics”—to address the polycrisis and build a future worthy of the human family. Although this second section presents serious arguments against what currently seem to be “alternative directions,” it does so in the synodal spirit of inviting Catholics with different views on Catholic Social Teaching (CST) to consider how they might refocus their efforts to build a broad coalition of those willing to work in a mode of social friendship for the future of the nation, the world, and the Church.

These first two sections, therefore, (i) sketch a multifaceted crisis and (ii) encourage Catholics to draw upon the resources of our social tradition in response to it. In this introductory essay, I had highlighted the importance of the 2024 election, encouraging Catholics to give due note of the importance of our public institutions to the common good, especially in managing the polycrisis. Tragically, many American Catholics instead supported a candidate and party that had announced a plan—Project 2025, which has been initially implemented by DOGE—to deconstruct our public institutions to increase the power of an aspiring autocrat and his oligarchic supporters. These steps have put the American economy and the entire postwar international order in a position of unprecedented peril.

During the last several months of Francis’s pontificate, the Vatican inaugurated the Jubilee year on the theme of hope, which balances the need for a realistic recognition of the polycrisis with the hope that we can face it with God’s help, as I have discussed in the following post.

Pilgrims of Hope and Agents of Fraternity

As is evident from his social encyclicals including the 2015 Laudato si’: On Care for Our Common Home (LS) and the 2020 Fratelli Tutti: On Fraternity and Social Friendship (FT), Pope Francis is acutely aware of the grave challenges that threaten the human family. In

The next two essays also align with Pope Francis’s social vision by addressing the need for a reformed economic paradigm after the failure of the “market fundamentalist” version of neoliberalism that was ushered in with the Presidency of Ronald Reagan.

Towards A New Economics

The first of these is entitled “Toward a New Economics,” and is offered by Anthony Annett of Fordham University.

This chapter makes the case for a new social democratic era, underpinned by the principles of Catholic social teaching. Following a highly successful original social democratic movement in the postwar period, there was a sharp turn in the neoliberal direction over the past four decades. This experiment largely failed, leaving behind vast amounts of inequality, exclusion, and environmental devastation. The chapter makes the case that neoliberalism can be traced to the principles of neoclassical economics, which are inferior to those of Catholic social teaching in the sense of being less in tune with human nature and less likely to generate healthy economies. It then discusses the roles of government, business, and labor, arguing that all economic activity—whether public or private—must be oriented toward the common good. Following this, it goes on to describe three core economic challenges that hinder human flourishing and undermine the common good: the crisis of employment, especially in the context of technological change; the crisis of inequality, as sharp divisions arise between rich and poor; and the crisis of environmental devastation, with particular attention paid to climate change. The final section argues for a new social democratic moment capable of addressing these challenges using the principles of Catholic social teaching.

A New Vision for the Economy

The next essay is entitled “A New Vision for the Economy: Social Catholicism in the 21st Century,” by Matthew Shadle, which also engages with Francis’s environmental work. The abstract reads as follows:

Faith in neoliberalism has been on the decline since the financial crisis of 2007–8. Catholic social teaching (CST) offers a compelling alternative view of the economy, yet “social Catholicism,” the network of associations that historically has put CST into action, is in a decades-long state of dormancy. At its height in the middle of the twentieth century, social Catholicism went into decline starting in the 1950s as a result of secularization and the globalization of the economy. If social Catholicism is to have a future in the twenty-first century, it needs a new vision that responds to contemporary reality. Pope Francis offers such a vision with his teaching on “integral ecology,” which turns to the ecosystem as a root metaphor for thinking about economic life. Building on this ecological vision, the economy can be conceived as an open, complex, and nonlinear system that can be gradually but radically transformed by the participation of individuals and organizations guided by CST. This ecological vision leads to a new way of thinking about business enterprises, social movements, and church-affiliated communities focused on linking faith and economic life that can give life to social Catholicism in the twenty-first century.

Yet another essay in Social Catholicism draws significantly on the socio-political thought of Pope Francis. This is the epilogue by Paul Vallely.

After Populism and Polarization: A Better Kind of Politics

The abstract for Vallely’s epilogue reads as follows:

A new populism has arisen in many Western democracies as a backlash to the growth of twentieth century economic globalization which has promoted increasing inequality within nations and left large swathes of the population feeling alienated, dispossessed, or “left behind.” This new populism has its roots in a mix of economic, philosophical, social and cultural factors. It feeds on a discontent which has found articulation initially outside mainstream politics in the US through movements like the Tea Party and in the UK by anti-European movements like UKIP. But it has spread into mainstream politics all over the world under Donald Trump, Boris Johnson, Viktor Orbán, Matteo Salvini, Giorgia Meloni, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, Jair Bolsonaro and Narendra Modi. Its discontents manifest themselves in divisive debates on national identity and immigration. Pope Francis proposes a “better kind of politics” that grows out of a healthy “theology of the people” who work in solidarity to foster ways of living consistent with human dignity. Within this new politics, progressive and metropolitan liberals must build alliances with the “Left Behind” to help them become agents of their own destinies and to recover their sense of dignity.

What I have outlined above offers just a thin sketch of the social vision of Pope Francis, including how it can help us to understand and address the grave challenges facing the human family. Readers who would like to be part of the efforts to build a world marked by social friendship, will find these and other essays in Social Catholicism for the Twenty-First Century?