Liberalism, Conservatism, Social Catholicism

On Recovering a Properly Catholic Socio-Political Orientation

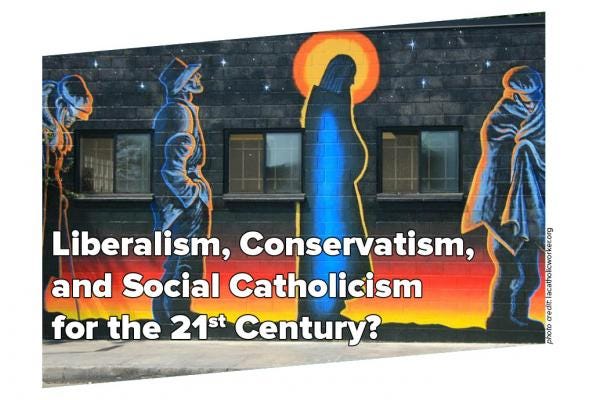

In this post, I will briefly introduce an essay I wrote that is entitled “Liberalism, Conservatism, and Social Catholicism for the 21st Century.” It is included in Social Catholicism for the 21st Century? Volume 1: Historical Perspectives and Constitutional Democracy in Peril. The purpose of the essay was to locate—within a context in which we must seemingly choose either the left/liberal or right/conservative tribe—the “social Catholicism” that follows from living out the “integral and solidary humanism” of Catholic Social Doctrine in the modern world of Constitutional Democratic states.

It therefore complements the essay Drew Christiansen’s “The Gospel and Human Dignity: Liberalism and Catholicism in Dialogue,” which I introduced in a previous post. A key takeaway from that post was that the Catholic magisterium and our social soctrine, since at least Pope St. John XXIII, have embraced the key tenets of liberalism including “human rights, constitutional government, democratic participation, the self-determination of peoples, and the equality of persons, especially women.”

The abstract of my essay begins as follows:

Between a brief introduction and conclusion, this essay sketches a historical narrative of how especially American Catholics can understand the contemporary state of both liberalism and conservatism in relation to a proposed renewal of social Catholicism to foster a “better kind of politics” to address the challenges facing the human family. The first half focuses on liberalism, tracing it from its remote roots, through the American founding, through key nineteenth century developments, through twentieth-century reforms in rough alignment with the development of modern Catholic Social Teaching leading to the postwar “liberal consensus,” and later to the so-called “end of history” followed by decades of globalization according to a market fundamentalist form of neoliberalism that has now broken down, with a resulting rise of populism, illiberalism, and postliberal integralism.

A primary source upon which I draw for this first half is an acclaimed book by James Traub entitled What Was Liberalism?: The Past, Present, and Promise of a Noble Idea. It presents an efficacious antidote to influential Catholic thinkers who demonize liberalism as an ideology of unconstrained freedom, while providing no plausible alternative to the key tenets of liberalism presupposed by contemporary Catholic Social Doctrine. I will discuss other recent literature on liberalism in future posts.

The synopsis of Traub’s book reads as follows:

A sweeping history of liberalism, from its earliest origins to its imperiled present and uncertain future.

Donald Trump is the first American president to regard liberal values with open contempt. He has company: the leaders of Italy, Hungary, Poland, and Turkey, among others, are also avowed illiberals. What happened? Why did liberalism lose the support it once enjoyed? In What Was Liberalism?, James Traub returns to the origins of liberalism, in the aftermath of the American and French revolutions and in the works of such great thinkers as John Stuart Mill and Isaiah Berlin.

Although the first liberals were deeply skeptical of majority rule, the liberal faith adapted, coming to encompass belief in not only individual rights and free markets, but also state action to provide basic goods. By the second half of the twentieth century, liberalism had become the national creed of the most powerful country in the world. But this consensus did not last. Liberalism is now widely regarded as an antiquated doctrine. What Was Liberalism? reviews the evolution of the liberal idea over more than two centuries for lessons on how it can rebuild its majoritarian foundations.

The essay also discusses the history and forms of conservatism drawing upon respected contemporary literature, including Edmund Fawcett’s acclaimed Conservatism: The Fight for a Tradition. The relevant section of the abstract continues as follows:

The second half similarly traces the rise of conservatism rooted in a widespread and understandable disposition to moderate change. A narrative of conservatism is traced through its modern founding in the thought of Edmund Burke, through the so-called “fusion conservativism” of the Reagan era, through the neoconservative era, and through the rise of radical forms of right-wing illiberalism.

It argues that while Catholics informed by our social tradition will reflect the best insights of the conservative tradition, the authentic living out of their faith will make them active and indispensable participants in the continual renewal of our constitutional democracies to meet the challenges of [what global thought leaders increasingly call] “the polycrisis” while eschewing the illiberal excesses of the left and right.

The essay concludes with brief remarks on the tradition of social Catholicism, which I have introduced in previous posts as a participative, reformist, dialogical, humanistic, and principle-driven mode of collaboration in society inspired by the fundamental Christian virtue of charity, which appears as a form of social friendship. It looks nothing like attempts of today’s postliberals to align with aspiring autocrats so the coercive power of the state can be employed to enforce a distorted understanding of Catholic morality—one difficult to align with the noble virtues of justice, prudence and charity—upon an unwilling population.