The Legacy of Jimmy Carter for Catholics?

A Recent Biography and His 1977 Notre Dame Commencement Address

As someone who grew up amidst the economic stagflation, geopolitical decline, and overall “malaise” of the 1970s, my appreciation for President Jimmy Carter’s (1977-81) character, intelligence, and diligence were accompanied by—at best—ambiguity regarding his effectiveness as President. His recent passing at 100 years of age offers an occasion to reconsider his legacy in greater detail. Such reconsideration will show that—despite his serious deficiencies as a politician1— the best contemporary scholarship on Jimmy Carter’s presidency shows that it merits a more balanced assessment, including an appreciation of the obstacles he faced and his significant achievements. Carter’s accomplishments, moreover, reflect a close symbiosis with Catholic Social Teaching (CST), as was recognized by his friend and collaborator Fr. Ted Hesburgh, who I discussed in a prior post.

Assuming the United States will have an opportunity to depart in the future from our current path toward “illiberal democracy” and oligarchy at home combined with “might versus right” foreign policy abroad, it will be important for American Catholics to develop a better understanding of how alternative paths—ones that aligned closely with CST—have born good fruit in the past, and how we got diverted from them.

[Jimmy Carter laughing with Pope John Paul II. Getty Images, Betteman.]

Introduction: A Commonly Held, but Deficient, Perspective

Given the economic and geopolitical struggles of 1979-80 that marked the last two years of Carter’s administration, the charges of his many critics that he was a weak and incompetent leader resonated widely. The economy, for example, was marred by high inflation (averaging 9.9% during his term),2 which the Federal Reserve combatted by pushing interest rates to a whopping 16.64% by the time he left office. In the long struggle of the Cold War, national confidence was still wounded by the ongoing effects of the preceding decade of calamities. These included the Vietnam War, the release of the Pentagon Papers that documented the lies of multiple administrations about the war, and the various scandals of the thuggish Nixon Administration, especially Watergate. Our primary Cold War adversary, the Soviet Union, had just invaded Afghanistan, while continuing to sponsor communist insurgencies as close as Nicaragua. Domestically, the sexual revolution was still ascendant, and social conservatives who feared this would undermine the family unit were on the defensive with the recent Roe V. Wade decision of the Supreme Court. Such factors led to a broad consensus that Carter was a failed president.

Having lived through this period of so-called “national malaise,” I was delighted—in 1984—to begin my first career in information technology with IBM during an economic boom and a time of rising optimism. The Reagan Administration was not only juicing the economy through tax cuts, deregulation and a massive military buildup. It was also taking a stronger geopolitical stance against an expansionist Soviet Union. Domestically, the administration was providing at least rhetorical support for “family values” against the sexual revolution. The famous “Morning in America” advertisement from Ronald Reagan’s 1984 Presidential campaign captured the spirit of the times for me, and for many.

[1984 Reagan Campaign Ad: Morning in America]

This new era also resonated with many American Catholics who increasingly became Reagan Republicans, facilitated by a largely unrecognized but accelerating effort to court them into a new coalition. As a growing number of informed citizens now understand, however, these efforts were part of the growing response of business interests to the “master plan” of the 1971 Powell Memorandum that can be seen as planting the seeds that have grown into Project 2025. This memorandum called on business leaders to invest their financial resources in a long-term project to increase their political power against the challenge posed to it by the growing, and more politically-engaged, postwar middle class seeking to realize the American dream, one that is increasingly out of reach.

After distinguishing himself as a lawyer for the Tobacco Industry, Powell’s memo accelerated efforts to build an array of lobbying firms, think tanks, and media outlets dedicated to selling what Naomi Oreskes and Eric Conway have called “The Big Myth.” This myth was that the public institutions—that the most recent Nobel Prize in Economic Science recognize as foundational to the common good—were to be loathed, and the mythical “free market” was to be sought. Naive to the unfolding of this master plan into oligarchic rule, largely through the incredible power of propaganda, I had joined the Conservative Book Club. Through it and other sources, I and was becoming familiar with the pillars of conservativism, including not only contemporaries like Reagan, William F. Buckley, Jr., and Patrick J. Buchannan, but earlier luminaries ranging from foundational thinker Edmund Burke (1729-97) to twentieth century giant Russel Kirk (1918-94).

Although I think there are many valuable insights from the conservative tradition, in different ways, all these conservatives shared the view that elites of some sort should be in the forefront of political rule. There is some truth to that, such as the fact that we obviously want informed, virtuous leaders as distinguished from ignorant and vicious ones. This truth, however, merits careful discussion, especially because—for example—those without education or wealth often have the clearest understanding of the injustices suffered by the outcast.3 I would argue, moreover, that the legitimate insights of the conservative tradition have been coopted into an oligarchic takeover of the United States, the outlines of which are well-portrayed in the above “Requiem for the American Dream.” Although Catholics have been instrumental in this slide into the oligarchy feared by the American founders, they have done so contrary to Catholic Social Doctrine, and against those—like Jimmy Carter—rightly seeking to foster an integral human development that raises everyone to an existence worthy of the human person.

Although many—myself included—might have been happy by the 1980s to forget about Jimmy Carter and the years of malaise associated with him, his busy post-presidency of indefatigable philanthropic efforts gradually led to a new consensus. This was that, “even if Carter was a failed president, he was perhaps our best post-president.” In what follows, I will first summarize several points from a recent biography that suggests a more balanced, positive, and defensible view of Carter’s political accomplishments. In the second part, I will recall Carter’s 1977 Commencement Address at the University of Notre Dame in which he lays out a foreign policy agenda centered on advancing human rights, which aligns closely with a similar emphasis in Catholic Social Doctrine since the postwar era.

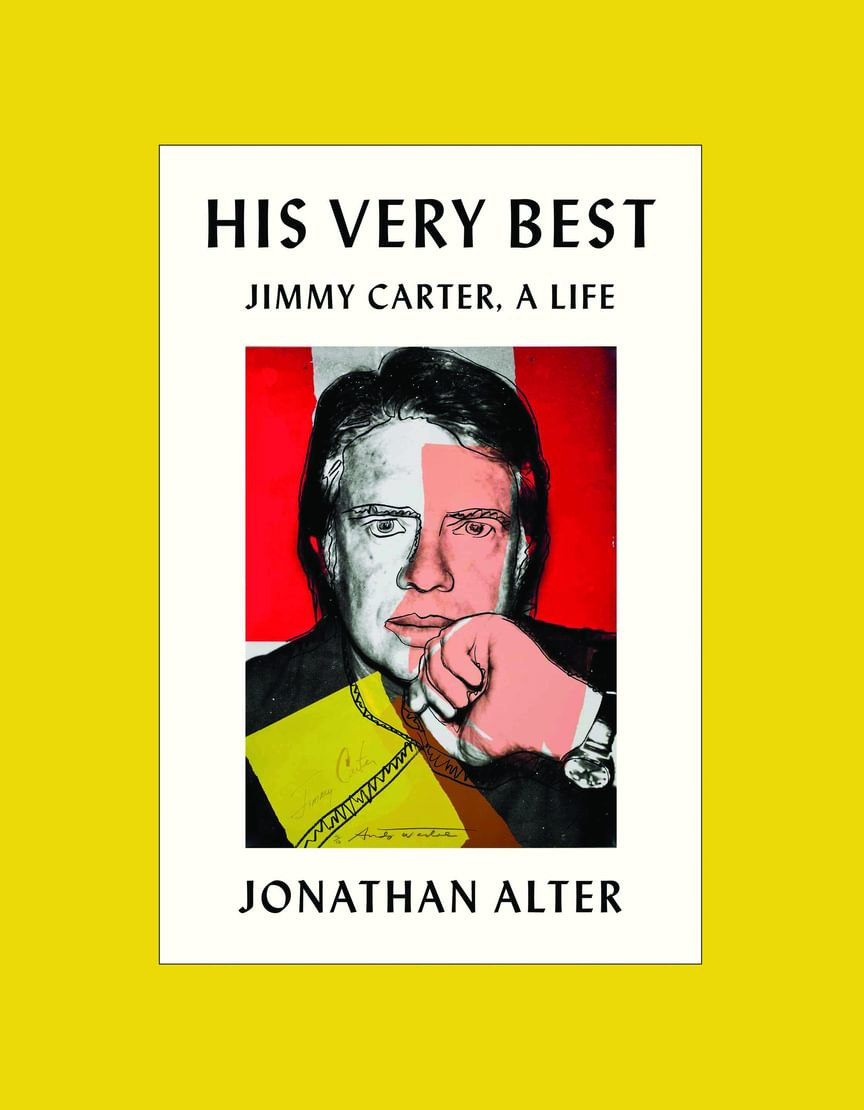

His Very Best: Jimmy Carter, A Life by Jonathan Alter

For those who are reasonably concerned about the prospects of an incoming administration that promises to deconstruct our public institutions and adopt an illiberal political and geopolitical stance reminiscent of interwar Europe, this recent biography by Jonathan Alter offers rich food for thought. It does so by offering what may well be the definitive account of the life and work of a president who, although reflecting various deficiencies as a political leader and widely held in disrespect after he left office, had an underappreciated set of strengths and accomplishments. Because these not only contrast so clearly with our incoming administration, but also align with key aspects of a Catholic social vision, they may be helpful to consider especially if the incoming administration is as harmful to the common good as I have every reason to expect. The synopsis of Alter’s book from the Amazon website reads as follows.

Jonathan Alter tells the epic story of an enigmatic man of faith and his improbable journey from barefoot boy to global icon. Alter paints an intimate and surprising portrait of the only president since Thomas Jefferson who can fairly be called a Renaissance Man, a complex figure—ridiculed and later revered—with a piercing intelligence, prickly intensity, and biting wit beneath the patented smile. Here is a moral exemplar for our times, a flawed but underrated president of decency and vision who was committed to telling the truth to the American people.

Growing up in one of the meanest counties in the Jim Crow South, Carter is the only American president who essentially lived in three centuries: his early life on the farm in the 1920s without electricity or running water might as well have been in the nineteenth; his presidency put him at the center of major events in the twentieth; and his efforts on conflict resolution and global health set him on the cutting edge of the challenges of the twenty-first.

“One of the best in a celebrated genre of presidential biography,” (The Washington Post), His Very Best traces how Carter evolved from a timid, bookish child—raised mostly by a Black woman farmhand—into an ambitious naval nuclear engineer writing passionate, never-before-published love letters from sea to his wife and full partner, Rosalynn; a peanut farmer and civic leader whose guilt over staying silent during the civil rights movement and not confronting the white terrorism around him helped power his quest for racial justice at home and abroad; an obscure, born-again governor whose brilliant 1976 campaign demolished the racist wing of the Democratic Party and took him from zero percent to the presidency; a stubborn outsider who failed politically amid the bad economy of the 1970s and the seizure of American hostages in Iran but succeeded in engineering peace between Israel and Egypt, amassing a historic environmental record, moving the government from tokenism to diversity, setting a new global standard for human rights and normalizing relations with China among other unheralded and far-sighted achievements. After leaving office, Carter eradicated diseases, built houses for the poor, and taught Sunday school into his mid-nineties.

Earnest Striving

Some of the most interesting points for me included Carter’s earnestness in striving to do “his very best” in everything, which explains the aptness of the book’s title (x). It reminds me of the magnanimity of Ignatian spirituality reflected in the motto of Ad maiorem Dei gloriam, of doing all for “for the greater glory of God.” Similarly illumining was Carter’s faith crisis that began in the early 1950s and intensified following his loss in the 1966 race for Governor of Georgia (135-8). Out of this long struggle, his Christian commitment was greatly deepened between the years of 1966-68 (138-44), with Carter then spending time in door-to-door evangelization. This deepening conversion helps to explain how Carter went from someone who largely stayed silent on racial segregation in Georgia to a strong champion of civil rights for African Americans and others. It also explains how the natural striving of a diligent engineer and world-class auto-didact came to be integrated within a more mature life of Christian service.

As a theologian, I was also pleased to learn that Carter read various serious scholars—including Catholic ones—to deepen his understanding of the Christian faith (139). Especially relevant to my concern with social ethics, Carter also studied leading authors on how Christian faith should relate to social and political life. In the early 1960s, for example, he came to consider—as his “political bible”—the recently published Reinhold Niebuhr on Politics: His Political Philosophy and Its Application to Our Age as Expressed in His Writings ed. by Harry R. Davis and Robert C. Good. From this work, Carter frequently recited from text that “the sad duty” of “politics [is] to establish justice in the world” (140).4 Although Carter’s social engagement was focused on practice and not scholarship, it was informed by ongoing study.

Response to Criticisms of Weakness and Incompetence

Alter also provides plausible responses to some of the primary criticisms of Carter as a president. In response to the widespread charge that Carter was weak, Alter provides a long list of the difficult decisions he made, rightly focusing on strength of character as distinguished from an understanding of strength based on political or military bullying. Put otherwise, Carter’s strength was in standing firm and working diligently to do what he saw as right, and not simply doing what is politically expedient or easy. Examples of such strength included supporting a Fed Chair to raise interest rates to defeat inflation, returning the Panama Canal to Panama, and declining to start a war with Iran over the hostages, among many others (xii-xiii).5 Another common charge was that Carter was incompetent, a charge that is not easily reconciled with his brilliance, his legendary work ethic, and his demonstrated competence in an incredibly wide range of fields (xiii).

These charges of weakness and incompetence were—not surprisingly—leveled especially by his political opponents. Such charges had salience with the public, however, amidst a difficult economy and the humiliation of the Iran hostage crisis, even if little of the blame for these problems could be laid at Carter’s feet.6

Inherited and Emerging Crises

The economic difficulties during the Carter administration centered in inflation and traced back at least to the Nixon Administration. The various causes for this inflation included the financing of the Vietnam war, the devaluing of the dollar in 1971 and 1973, Nixon’s pressuring of his Federal Reserve Chair to stimulate the economy to help his 1972 reelection campaign, and his lifting of an attempt at wage and price controls. Inflation also traced significantly to massive price hikes by the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC), which were partially in retaliation for American Support for Israel in the 1973 Yom Kippur War. None of these causes for inflation were Carter’s fault. The eventual victory over inflation, moreover, traced largely to Carter’s 1979 appointment of Paul Volcker as Federal Reserve Chair with a mandate to tame inflation through unprecedented interest rate hikes, with Carter recognizing that he would bear a heavy political price for presiding over them, just as he did for returning the Panama Canal.

Similarly, although “the buck stopped” on Carter’s desk for the hostage crisis that followed from the 1979 storming of the American Embassy in Tehran by student protesters, the blame for it lay primarily elsewhere. This crisis had deep roots tracing back at least to the American installation of the Shah of Iran in 1953, during the Eisenhower administration, with the involvement of then Vice President Richard Nixon. The ongoing presence of what the religious leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini considered an “American Puppet” provided an opportunity for him to stir up popular support by railing against American Imperialism. Alter devotes the entirety of chapter 29 to explaining the complex situation that led to “The Fall of the Shah.” He later devotes chapter 33 to describing how Carter was lobbied and deceived by former Secretary of State Henry Kissinger and other members in a Republican effort called “Project Eagle.” The initial phase of this project was to persuade Carter to go against his better judgment and allow the deposed shah to enter the United States, which they did by lying about the inability of Mexican hospitals to treat the shah’s terminal cancer. As Carter had feared, the American accommodation of the hated shah provided the provocation for the attack on the embassy in Tehran. The resulting hostage crisis, therefore, began on November 4, 1979, exactly 1 year before Carter would stand for reelection.

Although it might have been politically expedient for Carter to go to war against Iran over the hostages, he prioritized saving them, which he thought was most likely to happen through a negotiated release. This approach was criticized during the campaign as weakness, with Carter continuing to negotiate through election day. Although the polls were tied in the weeks before the election, they began to deteriorate as the 1 year anniversary of the hostage-taking approached. By election day of November 4, 1980, undecided voters broke decisively for his Republican opponent Ronald Reagan to give him an electoral college blowout.

Later evidence seems to prove conclusively, however, that the Reagan campaign was in touch with the Iranians, offering them a better deal if they kept the hostages until the Reagan administration came to power. The following story from the PBS News Hour provides a discussion of the evidence as of 2023, based on a story published by Peter Baker in the New York Times.7 As Jonathan Alter says in the interview below, “We do know for sure that there was a plot by the Reagan campaign to do Carter dirty.” Alter also discuses how the Iranians have admitted to meeting with Reagan campaign chair William Casey, and how an operative named Joseph V. Reed, Jr.—later rewarded with an ambassadorship—admitted in a letter to his family of having given his all to prevent Carter from freeing the hostages before the election (588). These efforts were part of the same “Project Eagle”—led by Reed—that had previously succeeded in getting Carter to welcome the shah into the United States for medical treatment. Alter writes that, after the shah died “Reed changed the original objective of Project Eagle from getting the shah into the United States to preventing the release of the hostages” (588).

[Jonathan Alter on PBS Newshour]

These “dirty tricks” with the Iranians seem to have evolved into the Iran-Contra scandal, involving an illegal provision of arms-for-hostages, that would mar the presidencies of both Reagan and his then Vice President George H. W. Bush. The Special Prosecutor’s investigation into this scandal, however, was obstructed for several years until it neared completion late during the presidency of Bush. He then thwarted the investigation by pardoning several operatives upon the advise of Attorney General William Barr, thereby ensuring their silence just before they were to testify.

Human Rights in Political Ethics: Carter’s Alignment with Catholic Social Doctrine

Since the postwar era, Catholic Social Doctrine has prioritized the promotion of human rights as central to upholding the dignity of the human person, to advancing justice, and to securing peace. Pope St. John XXIII’s 1963 social encyclical Pacem in terris: Peace on Earth can be understood as offering a comprehensive political ethics centered in human rights. In so doing, Pacem in terris echoed the 1948 Universal Declaration on Human Rights that was significantly inspired by the postwar efforts of leading Catholic thinkers, especially Jacques Maritain.

The following video captures not only Carter’s 1977 Commencement Speech at Notre Dame on Human Rights, but Fr. Hesburg’s introductory remarks which make clear their concurrence with each other on human rights, and with a political ethics following the 1948 Universal Declaration and Catholic Social Doctrine.

In these introductory remarks, Fr. Hesburgh paraphrases and cites President Carter’s inauguration day remarks to the world, which he delivered on Voice of America. I provide a rough transcription of how Fr. Hesburgh paraphrased Carter’s remarks.

President Carter promises to use the power and influence of the United States for good. He promises that our relations would be guided by the desire to shape a world order more responsive to basic human aspirations, and to create a just, peaceful, and stable world. He ensures the world that the United States seeks not to dominate or dictate to others.

President Carter humbly acknowledges that after 200 years, the United States was now more mature and recognizes the following. First, that we cannot alone lift from the world the terrible specter of nuclear devastation, but that we can and will work with others mightily to do so. Second, that we cannot alone guarantee the right of every human being to be free of hunger and poverty and political repression, but we can and will cooperate with others in combatting those enemies of mankind. Third, although the United States cannot insure equitable development of the world’s resources or the proper safeguarding of the world’s environment, but we can and will join with others in this work. We are not afraid to take the lead but welcome the participation from the whole world to move the reality of the world closer to the ideals of human freedom and human dignity.

In concluding, President Carter said to all the world, that you—our friends—can depend on the United States to be in the forefront of the search for world peace and human freedom, and to be sensitive to your concerns and aspirations. The problems of this world will not be easily solved, yet the wellbeing of each one of us, indeed our mutual survival depends on the resolution of those problems. And as President of the United States, I assure you that we intend to do our part and I ask each of you to join us in a common effort based on mutual trust and mutual respect.

Fr. Hesburgh’s introduction and President Carter’s address follows below, along with Carter’s address that illustrates not only the many parallels between the principles by which he sought to advance American foreign policy and the good of the entire human family. Carter’s address also shows the symbiosis between those principles and the ones advanced by the Notre Dame Center for Civil Rights in alignment with Catholic Social Doctrine.

The text of President Carter’s remarks are also available online, so I will omit them to keep this long post from getting further out of hand.

Conclusion:

The recent passing of Jimmy Carter offers an occasion to recall the extraordinary life of a seriously committed Christian who spent his century of earthly pilgrimage in loving service of God and neighbor. His pilgrimage was marked by striving to do “his very best” with every natural and spiritual gift—and with every minute—that God gave him. As I can only briefly indicate in this post, Carter’s magnanimous and well-informed stance of Christian service aligned him with the “integral and solidary humanism” of Catholic Social Doctrine to an extent that few today recognize. Much more could be said about the radically different world toward which such a Christian humanism would have led us. As we continue to see the nation and world that follow from our widespread departure from that path, Catholics have the opportunity to revisit the more narrow one from which we have departed. With the help of a God “who can do immeasurably more than we can ask or imagine” (Eph 3:20), and amidst a “world on fire,” the current year of jubilee calls us to somehow become “pilgrims of hope”, which—if I am not mistaken—would have us doing “our very best” to salvage a just, peaceful, and sustainable world for future generations.

Carter’s fundamental deficiencies as a politician followed from his strengths and inclinations. Possessing a piercing intellect, an exceptional work-ethic, a righteous Christian determination to do the right thing, a dislike for many key aspects of the political process, and communication skills—and political shrewdness—far inferior to someone like Ronald Reagan, Carter alienated many politicians, media personnel, and voters, limiting his effectiveness.

https://www.investopedia.com/us-inflation-rate-by-president-8546447#toc-jimmy-carter-19771981.

I have begun to sketch such a discussion in my “Liberalism, Conservatism and Social Catholicism for the 21st Century?” in Chicago Studies, 60:1 (Fall 2021/Winter 2022), a later version of which is included in my Social Catholicism for the 21st Century? Volume 1: Historical Perspectives and Constitutional Democracy in Peril, edited by and with contributions from William F. Murphy, Jr. (Eugene: Pickwick, 2024).

This insight has deep roots in the Old Testament, and—although it rarely gets due attention in contemporary Catholic life that is largely forgetful of our social tradition—is not abrogated but fulfilled in the New Testament teachings of Jesus Christ.

Alder’s partial list includes “pardoning Vietnam War-era draft dodgers; imposing nettlesome energy conservation measures; deregulating natural gas prices; canceling dams and other water projects; reducing troop levels in South Korea; canceling the Clinch River Breeder Reactor Project; canceling the B-1 bomber and the neutron bomb; signing the Panama Canal Treaties; returning the Crown of St. Stephen to Communist Hungary; cutting the budget; appointing a Federal Reserve Board Chairman to raise interest rates; imposing a grain embargo; boycotting the 1980 Summer Olympics; reinstating draft registration; not attacking Iran; resettling Cuban refugees; preventing the development of tens of millions of acres in Alaska.” (xiii).

This is not to deny Carter’ significant weaknesses as a politician, which included the way his honesty, self-righteousness, and distaste for much of the political process hindered his ability to cultivate the public support needed to win a second term.

Peter Baker, “A Four-Decade Secret: One Man’s Story of Sabotaging Carter’s Re-election,” (March, 18 2023) at https://www.nytimes.com/2023/03/18/us/politics/jimmy-carter-october-surprise-iran-hostages.html.

Really enjoyed this one, Bill. Nice job succinctly tying the recent past to present and giving Carter his due for trying to lead morally and honestly.