Fr. Ted Hesburgh, Social Catholic and Witness to Hope

A Priesthood lived for God, Country, and Notre Dame

In what follows, I will introduce the life and work of the man who was arguably the most prominent American social Catholic since the Second World War, Fr. Theodore Hesburgh (1917-2015) of the University of Notre Dame and the Congregation of the Holy Cross (CSC). As I will show, Fr. Ted—as he preferred to be called—is rightly understood as exemplifying the participatory, fraternal and unifying mode of socio-political engagement for the common good that we have seen in the social Catholics I have introduced in previous posts.1 Put otherwise, his life manifested the “integral and solidary humanism” of Catholic Social Doctrine, which is rightly understood as living out the life of virtue and holiness in the modern world, thereby sharing in Christ’s work of redemption and reconciliation.

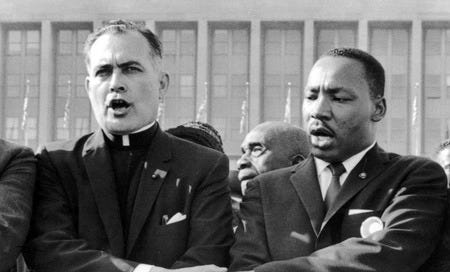

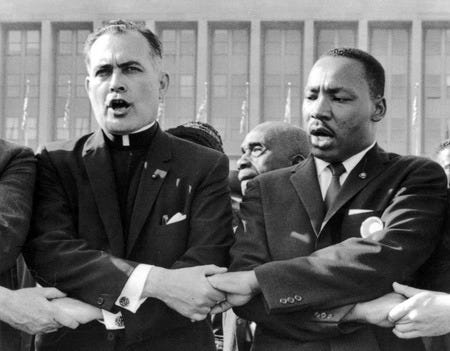

[Fr. Ted Hesburgh and Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. University of Notre Dame]

Because Fr. Hesburgh’s life and accomplishments were so numerous and manifest from the postwar years into the first decades of our century, he has often been the subject of wonder, praise, and even hagiography, all of which can be see in this trailer from a 2019 documentary on his exemplary life and work.

Since at least the early 1980s, however, many American Catholics embraced an alternative “socially conservative” stance that prioritized legal opposition to practices including abortion and same sex marriage. From this perspective, it seemed appropriate to move beyond celebratory and hagiographical accounts of Fr. Hesburgh to consider his legacy more critically. If abortion was indeed the preeminent social issue of the late twentieth century, and if the appropriate Catholic response was to build political alliances to outlaw it—along with other practices that destroyed human lives at their most vulnerable stages—then Fr. Hesburg’s model of broad participation and collaboration for the common good would seem to have been naive and misguided.

Now that—however—the “social conservatism” and “family values” promoted by the Republican Party have been largely replaced by some combination of populism, authoritarianism, and oligarchy—along with a systematic attack on the public institutions that are integral to the common good—it is perhaps a good time to reconsider the example of a man whose social vision aligns much better with the best of the Catholic tradition, and with the vision of the Second Vatican Council.

Presuming the broader trajectory of social Catholicism within which Fr. Hesburgh’s model of social and political engagement is properly understood, I will proceed in five steps. Much like I did with Msgr. John A. Ryan, the first will consider the formation that prepared Fr. Ted for his social ministry, a formation that included not just intellectual, but moral/character and spiritual dimensions. In the second step, I will sketch some of Hesburgh’s accomplishments in his primary apostolate in Catholic higher education. In the third, I will briefly note some of his activities and honors outside Notre Dame. In the fourth, I will acknowledge some of the critical questions that have been raised regarding his life and work, and offer some preliminary assessments and responses. This will prepare for my conclusion in the fifth section that Fr. Hesburgh provides another example of the fecundity of Catholic Social Doctrine which encourages us to enter into collaboration with our fellow citizens for the common good in a mode of social friendship and solidarity. In so doing, he serves as a witness to the hope that the Divine assistance is available to us as we work to address the grave challenges facing the Church, the nation, the human family, and the natural environment in our day.

1. Hesburgh’s Formation for Social Catholicism

Some key features of Fr. Ted’s formation are helpful for understanding how he came to exemplify the fraternal mode of socio-political engagement we can see in the 2004 Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church which introduces its subject matter under the heading of “an integral and solidary humanism.” Hesburgh was born in Syracuse, New York in 1917 to devout Catholic parents. He was educated in Catholic schools, served as an altar boy, described a clear desire to become a priest from the age of six, and maintained a strong identity as a priest throughout his long and fruitful life. Fr. Ted’s human and spiritual formation benefitted from close relations within his family, and from a strong Catholic culture centered in his parish and parochial school. Young Ted had a voracious appetite for learning and as a “youngster read the Encyclopedia Britannica volumes his parents had purchased for their home,” which helped him to develop “an interest in many areas” as one of his biographers, Fr. Wilson Miscamble, CSC writes.2

Fr. Ted’s facility for learning, for languages, and for leadership were evident by the time he graduated from Most Holy Rosary Parochial High School in Syracuse, NY and enrolled in Holy Cross Seminary in 1934. By 1937, his formators were further convinced of his promise and sent him to Rome for work on a bachelor of philosophy degree, which he completed in 1940. His time in Rome allowed him to add competence in Italian to his facility in Latin and French. This time in Europe and facility with languages gave Fr. Ted a cosmopolitan perspective, which would be deepened by his subsequent work and travel. Hesburgh’s philosophical studies also gave him a sound introduction to scholastic thought, which he always appreciated for providing him with a solid framework for engaging other intellectual traditions.

After returning to the United States, the young Fr. Ted completed his priestly formation in Washington, D.C. and was ordained a priest at Notre Dame in 1943, just four weeks after his 26th birthday. He was inspired by the inscription above the door of what is now Sacred Heart Basilica to dedicate his life to “God, Country and Notre Dame.” Out of his love for country and a zealous desire to live out the virtue of courage, he had asked upon ordination for permission to serve as a chaplain in the Navy but his superiors determined that his intellectual talents would be needed at Notre Dame after the War. Fr. Ted, therefore, followed their direction and continued his studies for a doctorate at the Catholic University of America in wartime Washington, D.C.. While doing so efficiently in three years, he also demonstrated his reputation for hard work by also participating actively in pastoral ministry. In a city teeming with those engaged in the war effort, Fr. Ted ran a vibrant United Service Organization (USO) club out of a Knights of Columbus hall in the city.

According to Miscamble, Fr. Ted’s doctoral studies focused on

Catholic Action, the lay activist movement identified with Fr. (later Cardinal) Joseph Cardijn of Belgium, who had founded the Young Christian Workers organization in the 1920s and guided its growth through the 1930s. [Fr. Ted] wanted to demonstrate how lay activity in the world emerged from the Church’s sacramental life. …in Hesburgh’s view baptism and confirmation prepared the layman (as he expressed it then) for his essential work in the world. …The dissertation clearly placed Hesburgh among those promoting an enhanced role for the laity. … He would later be a supporter of efforts to spread Cardijn’s movement and methods to Notre Dame and beyond. And he saw the Second Vatican Council’s teaching on the role of the laity in such documents as Gaudium et Spes (Joy and Hope)—the Pastoral Constitution on the Church in the Modern World—as fulfilling the thesis he had put forward almost two decades before. He would explain and justify major decisions at Notre Dame in the 1960s as designed to enhance the role of the laity.

We can see that multiple aspects of Fr. Ted’s formation prepared him to foster—and exemplify—his unique and fruitful mode of Catholic participation in American democracy. These begin with his promise to live his priesthood for God, Country and Notre Dame. They include the realization of his priestly vocation during the Second World War. They also include his doctoral studies which anticipated the Second Vatican Council’s understanding of the Church in the modern world, and of the apostolate of the laity.

2. Fr. Ted’s Apostolate in Higher Education

After joining Notre Dame’s faculty in 1945, Hesburgh was asked to chair the Department of Theology in 1948. After just one year, he was appointed in 1949 to serve as Executive Vice President, and then as President in 1952 at the age of only 35. Fr. Ted served in that role for 35 years before becoming President Emeritus in 1987, and passing on to his reward in 2015 at the age of 97. As president, Fr. Ted embarked on an magnanimous program to change Notre Dame from a football school with a strong Catholic culture—but a mediocre academic reputation—into a great university.

His ministry had what we might call an ad intra dimension, focused on the pursuit of excellence at Notre Dame, which was also intended to prepare graduates to live out their faith in the world. It also included an ad extra dimension, focused on exemplifying service to the national and world community.

Both within the Church and in the broader society, Fr. Ted’s achievements were arguably unrivaled among American Catholics. An initial sense of these achievements can be gained from the previously linked trailer to the 2019 documentary entitled Hesburgh. A fuller sense can be gained by streaming the complete documentary through Amazon Prime, or through his autobiography and multiple biographies. From these, we can become familiar with the life and work of a priest whose long list of accomplishments are reminiscent of the fictional character Forrest Gump, except in Hesburgh’s case, the accomplishments were real.

Pursuing Academic Excellence

During his long tenure as President of Notre Dame, Fr. Hesburgh oversaw the transformation of the school from academic mediocrity into a nationally respected institution of higher learning. This transformation was reflected in a 19-fold increase in operating budget, a 39-fold increase in endowment, a 20-fold increase in research funding, a near doubling of student enrollment, similar doublings of faculty and of the number of degrees conferred annually, an almost ten-fold increase in faculty salary, the establishment of over 100 distinguished professorships, and dozens of building projects.3 Fr. Ted also oversaw the transition of Notre Dame to a coeducational institution in 1972.

During his tenure at Notre Dame, Fr. Hesburgh was also the most influential leader in American Catholic higher education. Well over a decade after the historian Msgr. John Tracy Ellis published his 1955 essay on “American Catholics and the Intellectual Life,” leaders of American Catholic higher educational institutions were still struggling to chart a path to improve the generally poor academic reputations of their institutions. As already noted, by the late 1950s, efforts to provide a distinctively Catholic intellectual formation grounded in Thomism had apparently run out of steam, which meant that academic excellence would be defined largely by secular standards.

With what was understood as an existential threat to the viability of Catholic Colleges and Universities, and in the wake of the Second Vatican Council, in 1967 Hesburgh “convened twenty-six North American educators at Land O’Lakes to prepare a paper for the International Federation of Catholic Universities (IFCU) meeting scheduled to take place the following summer.”4 They “produced a relatively brief statement entitled ‘The Nature of the Contemporary Catholic University’” which—controversially—understood Catholic universities largely in terms of their participation in the modern educational establishment (121). The key formulation reads as follows: “‘To perform its teaching and research functions effectively the Catholic university must have a true autonomy and academic freedom in the face of authority of whatever kind, lay or clerical, external to the academic community itself.’”5 While serving as President of Notre Dame, Fr. Hesburgh had experienced various attempts at censorship from Church officials in Rome, including an attempt to prevent the publishing of John Courtney Murray’s work on religious freedom that would later influence the momentous breakthrough of the Second Vatican Council. Based on this experience, Hesburgh considered such academic freedom as essential to the intellectual integrity of Catholic universities, and to their service to the Church. This will be a contested part of his legacy.

3. Activities and Honors Outside Notre Dame

Besides his long priestly ministry centered in educational leadership at Notre Dame and beyond, Fr. Hesburgh was busy as a public servant and social activist, spending an estimated 40 percent of his time engaged in service off campus, which was only possible through the loyal support of his talented collaborator at Notre Dame, Fr. Edmund P. Joyce. Hesburgh’s engagement in public service was informed by his hope that well-intentioned people could work together to solve any problem, so he entered energetically into collaborative efforts to solve a wide range of the most urgent challenges accompanied by his continual prayer of “Come, Holy Spirit.”

Treating Hesburgh’s long list of accomplishments has already been the subject of multiple biographies. For my purposes, they begin with “sixteen presidential appointments involving some of the major social issues of his era: civil rights, campus unrest, Third World development, peaceful uses of atomic energy, and immigration reform, ‘including the American policy of amnesty for immigrants in the mid-1980s.’”6 His work on the U.S. Civil Rights Commission—for example—began in 1957, when President Eisenhower made him a member; it included his decisive contribution to fostering the consensus that eventually led to the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which was followed by the Voting Rights Act of 1965. Hesburgh then chaired the Civil Rights Commission from 1969 until he was asked to resign by the Nixon Administration. This resulted from his speaking out against the administration’s deployment of Nixon’s “Southern Strategy,” through which he sought to attract the support of especially southern racists by obstructing progress on civil rights while pretending to advance them.

Fr. Hesburg’s first presidential appointment had been to the National Science Board, which led to various other scientific appointments in the public and private sectors. At one point, he was even offered—but declined—the number two position at NASA with an understanding that he would quickly advance to lead the agency. He also declined an offer to take the Vice Presidential slot on the Democratic Party Ticket. Fr. Hesburgh also served the Vatican as both permanent observer at the United Nations, and as representative on the International Atomic Energy Commission, which got him involved in arms control negotiations between the United States and the Soviet Union.

4. Raising Critical Questions Beyond Hagiography

Given the wide range of celebratory and hagiographical accounts of Hesburgh’s life, it is not unreasonable that a professional historian would strive to offer a critical assessment of his legacy. A substantial and sincere attempt at this was offered by his confrere, Fr. Wilson D. Miscamble C.S.C. in his previously cited 2019 biography American Priest: The Ambitious Life and Conflicted Legacy of Notre Dame's Father Ted Hesburgh. Readers are encouraged to read the whole book, or listen to the audible version, as I can only touch on a few points that are most relevant to a possible renewal of social Catholicism.

Miscamble offers a critical engagement with Hesburg’s accomplishments in several areas. On many of these, such as Fr. Ted’s work in civil rights, Miscamble’s assessment is largely favorable and uncontested. He also largely grants that Fr. Ted was decisive in transforming Notre Dame into a widely-respected university according to American standards, which was no mean feat. As a distinctively Catholic university, however, Fr. Miscamble assessment is more mixed. He grants, for example, that Hesburgh maintained the Notre Dame campus as an exemplary “Catholic neighborhood,” and even that he made the university a prominent crossroads for intellectual exchange. He is largely critical, however, of Hesburg’s efforts to move the governance of Catholic universities—including Notre Dame—away from ecclesiastical control and towards that by laity, although this complex discussion is beyond my present scope.

On other points, Miscamble’s assessment is also critical but seems sound, such as that regarding Hesburgh’s departure from the “Collegiate Gothic” architecture, to which the University subsequently—and, in my opinion, wisely—returned. It also seems reasonable for Miscamble to have charged—for example—that the theology department became too “liberal” under the leadership of Fr. Richard McBrien, who was not only ubiquitous in print and broadcast media. He was also an outspoken advocate for progressive reforms and critic of many of the priorities of Pope John Paul II. Even if McBrien proved prescient on many points, such as the links between a kind of clericalism and especially the coverup dimension of the sex abuse crisis, it seems clear that an outspoken and critical “liberal” stance regarding the Church does not inspire many young to study theology or give their lives in service to the Church.

On the other hand, Fr. Hesburgh had previously tried to recruit the young Fr. Joseph Ratzinger, which would have been a great addition to the faculty. If the department had been able to balance the presence of leading progressive reformers like McBrien with great ressourcement theologians like Ratzinger, along with those exemplifying a renewed Thomism in dialogue with the modern world, I think that would have been ideal. Given the state of Catholic intellectual life, however, it was not possible at that time, nor is it easily realizable today, especially because today’s leading ressourcement and Thomistic scholars in the United States seem more inclined toward postliberalism and integralism than toward Catholic Social Doctrine, or with efforts to preserve and renew American democracy.

Miscamble also judges that Fr. Hesburgh’s efforts to make Notre Dame great—precisely as a Catholic University—have been unsuccessful, on two primary grounds. These include the content of the curriculum—especially regarding Catholic theology and philosophy—and the teaching of such content by practicing Catholics. I will focus on the first point about content.

Thomism and Integration of the Undergraduate Curriculum

Regarding the content of the undergraduate curriculum, Hesburgh abandoned his early goal of having an updated Thomism play an integrating role, inculcating what its proponents call a sapiential perspective. It would also be valuable in introducing students to arguably the primary point of reference in the Catholic intellectual tradition, while further illustrating the Catholic harmony between faith and reason. After some initial efforts towards curriculum reforms to incorporate an updated Thomism, however, Fr. Ted came to abandon this goal.

A primary reason for doing so was that—by the late 1950s—confidence in such a project was waning among Catholic intellectuals, and it would not recover in the decades immediately following the Second Vatican Council. This waning confidence related to the relatively low academic quality of Catholic higher education that was an ongoing topic of discussion, with the theology manuals derived from scholastic theology seen as part of the problem. The lack of confidence in the importance of scholastic thought in Catholic higher education also reflected the desire that such institutions engage in contemporary American intellectual life, and in addressing current social challenges as Fr. Ted exemplified through his public life.

With the help of hindsight, I’m sympathetic to the argument that Notre Dame—and Catholic higher education as a whole—would have done well to maintain a serious dialogue with a renewed Thomism in the undergraduate curricula. Part of that argument would be based on the revival of Thomistic thought in recent decades based largely—it seems—on a renewed appreciation of its intrinsic merits, some of which I have mentioned above. This revival can be seen in the wealth of Thomistic scholarship published in recent decades,7 and in the place that Aquinas has gained in the curricula of especially conservative Catholic colleges and universities in the United States. It can also be seen in the interest in Thomistic thought among students at a wide range of secular universities, as demonstrated by programs like the Thomistic Institute, which boasts chapters at over 80 institutions, including several of the most prominent ones.

A Lacuna in the Contemporary Revival of Thomism

I have already indicated, however, a key deficiency in this contemporary renewal of Thomism in especially the United States. That is, its significant disconnection from the postwar reconciliation between Catholicism and constitutional democracy as reflected in Catholic Social Doctrine. Although Thomists like Jacques Maritain and Yves Simon had been indispensable to the postwar reproachment between Catholicism and the “modern world” of constitutional democratic states, there is a noticeable lack of prominent contemporary Thomists fostering the renewal of constitutional democracy.8 By being—at best—absent from the struggle to preserve and renew American democracy, the contemporary Thomistic revival is also largely absent from efforts to address the great challenges now facing the human family. These challenges—which can be met only through strong public institutions—include those emphasized by Pope Francis in his social encyclicals Laudato si: On Care for Our Common Home (2015) and in Fratelli Tutti: On Fraternity and Social Friendship (2020). An even more critical stance toward liberal democracy is evident among leading American scholars in the ressourcement tradition, as I have discussed elsewhere.9

I have previously touched upon how an emphasis on metaphysics and order—such as that evident in contemporary ressourcement and Thomistic scholarship—has often aligned with a lack of attention to the great practical challenges facing the human family, including the authoritarian and oligarchic threat to democracy. The fact that these key contemporary streams of Catholic thought are—to the present day—of little help in addressing such grave practical challenges facing the human family needs to be kept in mind when assessing criticisms of Fr. Hesburgh’s failure to integrate the curriculum through Thomism. To be clear, however, there is no reason why Catholics working from the Thomistic and ressourcement traditions should not support constitutional democracy, as does Catholic Social Doctrine which draws on both, and I presume such Catholics reject authoritarianism and oligarchy.

Because much of the “institutional infrastructure” of the Catholic Church in the United States—the clergy, the media, the academics—has come to see what I call “postliberal ressourcement Thomism” as the standard for Catholic orthodoxy, any widespread renewal of the social apostolate will need to be in dialogue with these intellectual movements. A renewal of social Catholicism would also require a repositioning of American Catholics to be less aligned with what remains of the “socially conservative” coalition formed in opposition to abortion, and be more informed by Catholic Social Doctrine.

The most severe criticisms of the socio-political stance and activities of Fr. Hesburgh, moreover, came from the perspective of this social conservatism, with which postliberal ressourcement Thomism also aligns. According to this perspective, Hesburgh misread the “signs of the times” by failing to recognize that abortion was the preeminent moral challenge of the day. The purported explanation for his doing so was his allegedly disordered desire for acceptance and esteem among the liberal elite.10 This line of criticism seems to reflect more a commitment to a different—namely socially conservate, and abortion-centered—politics, than a sober and charitable consideration of Fr. Ted’s life and work. The obvious and just way to consider his work is according to the “integral and solidary humanism” of Catholic Social Doctrine, of which he was an exemplar. Ken Woodward offers a more detailed response to these criticisms of Hesburgh.

5. Conclusion: Fr. Ted as Social Catholic and Witness to Hope

Although Fr. Ted built an exemplary reputation through especially his 35 years as President of Notre Dame, his socio-political stance of collaborative engagement and service within American constitutional democracy seemed obsolete as Catholics became increasingly integral to the socially conservative side of the culture wars. Now that conservatism has evolved into some combination of populism, authoritarianism and oligarchy, we now face the serious threat of a dystopian future, especially given the threat to the institutions that are integral to the common good. In such a situation, we need models and sources of hope. Through his zealous labors in service of God, Country and Notre Dame, Fr. Ted exemplified how to work—with continual prayers for the assistance of the Holy Spirit—in a spirit of social friendship, confident that good people working together could solve any problem with God’s help.

I refer to the pathbreaking Bishop Wilhelm E. von Ketteler; the underappreciated Cuban priest-scholar Fr. Félix Varela; the foundational ressourcement thinker, defender of social Catholics and opponent of integralism Maurice Blondel; the prescient opponent of fascism Yves Simon; the American social reformer Msgr. John A. Ryan; the founder of Italian Christian democracy Fr. Luigi Sturzo, and with his fellow Italian social Catholics.

Wilson D. Miscamble C.S.C., American Priest: The Ambitious Life and Conflicted Legacy of Notre Dame's Father Ted Hesburgh (New York: Penguin Random House, 2019), 5.

Exact figures can be found on the Wikipedia page at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theodore_Hesburgh.

Miscamble, American Priest, 120-21.

As quoted by Miscamble, American Priest, 121.

For a helpful summary corresponding to what one finds in Miscamble’s, American Priest, see “Theodore Hesburgh,” https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Theodore_Hesburgh.

Scholars from the University of Notre Dame have contributed significantly to this contemporary renewal of interest in the thought of Aquinas. The university also recently hosted a major conference to celebrate “the 800th anniversary of the birth of Thomas Aquinas, exploring the ongoing importance of his thought to contemporary cultural, philosophical, and theological discussions.”

For a notable exception from 2012, see Martin Rhonheimer’s The Common Good of Constitutional Democracy: Essays in Political Philosophy and on Catholic Social Teaching , edited with an introduction by William F. Murphy, Jr. (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 2012). See also John P. Hittinger, Liberty, Wisdom, and Grace: Thomism and Democratic Political Theory, Applications of Political Theory (Lanham, MD: Lexington, 2002).

See especially my introduction to Social Catholicism for the Twenty-First Century? Volume 1 Historical Perspectives and Constitutional Democracy in Peril. In the same volume, see Thomas Howes, “Metaphysics, Ethics, and Politics: Can Natural Lawyers Embrace Liberalism?” See also my “Three Contemporary Alternatives to Social Catholicism” in Chicago Studies 61.2 (Spring/Summer 2023): 21-47.

See, for example, the conclusion to Miscamble, American Priest, especially 373-78, which intersperses some stinging criticisms amidst more favorable remarks. Besides the previously noted areas of curriculum and Catholic faculty, the most biting criticisms charge Hesburgh with “dependence on the regard and esteem of the liberal establishment” (374), personification of the “push for assimilation and acceptance,” “desire to be part of the elite circles of power and influence,” seeking the “regard of the higher education elite,” doing “too much ‘kneeling before the world’” (374). This desire for acceptance by the liberal elite allegedly led to Hesburgh’s failure to read well “the signs of the times” (375). He instead allegedly savored “the experience of working with the doyens of the establishment,” allowing himself to be “swayed or manipulated” by them, thereby accepting the role of the “accommodating and acceptable priest,” resulting in his supposed “ambivalence regarding extensive population control efforts supported by the Rockefellers,” tempering “his commitment on key moral issues” (377).