De Lubac's Memorandum On the French Bishops

His Assessment of their Response to the Nazi Occupation of France (1940-44)

Reminder: readers can view the following post, and dozens of other ones, at the Social Catholicism and a Better Kind of Politics website.

In 1944, the great theologian Henri de Lubac, SJ (1896-1991) wrote a memorandum summarizing his views on the behavior of French Catholic bishops during the Nazi occupation. He did so at the request of his friend Jacques Maritain, who had been living in the United States during the war as an exile. Maritain had been working to articulate a Christian humanism through which Catholics could participate fruitfully in a postwar world that seemed to be moving towards constitutional and representative forms of government after the horrors of fascism. Maritain was also wrestling with the fact that the Thomistic revival in France, with which he had been close, had failed to meet the challenge of interwar fascism such that leading neoscholastic intellectuals preferred fascism to democracy.

Given that the world now faces a frightening new age of authoritarian leaders, de Lubac’s reflections merit careful consideration, especially for contemporary Catholic leaders. Although our historical situation differs in many respects from the one about which de Lubac wrote, they also have some frightening features in common. It seems clear, therefore, that Bishops will need to learn how to minister in a very different socio-political context than the one that marked the “free world” of the last 80 years. De Lubac’s memorandum, however, is largely unknown to English language audiences. In what follows, therefore, I will first provide some of the relevant biographical data on de Lubac before summarizing the main takeaways from his memorandum.

Introducing Henri de Lubac, SJ

Henri de Lubac is widely recognized as one of the greatest and most influential Catholic theologians of the twentieth century. He had been born into an aristocratic French family and was instructed by the Jesuits before joining their Society in 1913 at the age of 17.1 The next year, however, he was drafted into the French army. In 1917, de Lubac suffered an injury to the head that resulted in a lifetime of recurring dizziness and headaches. After demobilization in 1919, de Lubac returned to the Jesuits. Within a few years of philosophical studies, he had become especially interested in the thought of the philosopher Maurice Blondel, whose work against integralism was foundational for the French Jesuit’s long-term and influential efforts to articulate the relation between nature and grace. For Blondel and de Lubac, it was essential to affirm that there was one order according to which every person was directed to their fulfillment in God. It was dangerous, on the other hand, to posit a distinct natural order in which people could find a kind of natural happiness, suggesting that supernatural fulfillment was an optional extra, like icing on a cake.

De Lubac began teaching in 1929, and continued extensive research that led to the 1938 publication of what would later appear in English as Catholicism: Christ and the Common Destiny of Man. Because this English subtitle gives a different sense from the French original,2 however, we should note that a literal translation of the French title would be “Catholicism: The Social Aspects of Dogma.” In this seminal work, therefore, de Lubac shows the essentially social and historical nature of Catholicism and of the Catholic Church. This social vision grows out of the New Testament and the fathers of the Church, and is richly reflected in the documents of the Second Vatican Council, and in the “integral and solidary humanism” of Catholic Social Doctrine.3

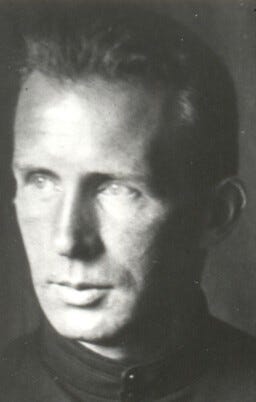

[An undated photo of a relatively young de Lubac from the International Association of Cardinal Henri de Lubac]

Besides his long-term interest in the relation between nature and grace, and in the related integralist temptation of Catholics to seek political power, de Lubac’s spirituality and theology were deeply shaped by the Pauline Christocentrism that I discussed in a recent post. Given his lofty stature by the time of the Second Vatican Council, de Lubac was a major influence on the documents it promulgated.

To understand the man who wrote the memorandum, we should keep in mind that de Lubac stayed in hiding in France during the Nazi occupation, and participated actively in the French resistance. He assisted, for example, in the publication of an underground journal called Témoignage chrétien (Christian Testimony), which argued for the incompatibility between Nazism and Christianity. Not surprisingly, some of his co-workers paid the ultimate price for this underground work.

De Lubac’s memorandum to Maritain was considered “strictly confidential” (267) when written, and was not available in an English translation until 2018, when it was published in the Journal of Jesuit Studies.4 It is not, however, a carefully researched and precisely written academic treatise but a memorandum, that nevertheless contains valuable insights.

As a new wave of authoritarianism threatens to spread across the globe, de Lubac’s assessment provides a valuable point of reference for a range of contemporary Catholic leaders. Even if it is not clear to what extent these contemporary leaders will face coercion or persecution from the new authoritarianism, it is part of the virtue of prudence to prepare the mind to deal with foreseeable circumstances.

In what follows, I provide extensive excerpts from de Lubac’s memorandum, which begins with a series of qualifications, reflecting the reluctance with which he writes. De Lubac makes clear that he is writing only at the request of his distinguished friend Jacques Maritain on what he calls “the matter of the bishops.” He notes that “he has neither the time, nor the desire” to give “a complete rendering” of a legally “thorny” issue that “is painful for the Catholic conscience.” Thus, he “only wishes to briefly mention a few points” (266).

De Lubac provides this memorandum “for illustrative purposes only,” to “report what he has heard in the public sphere or many times in private.” On the one hand, de Lubac writes that he does not want to speak “indiscriminately of all of [the bishops].” On the other hand, he writes that “their attitude…seemed to be so generalized that one feels allowed to speak collectively” (267). For these reasons, the memorandum reflects a mix of generalized descriptions of the way French bishops conducted themselves during the Nazi occupation and particular examples of how they did so. De Lubac also points to occasional examples of virtuous action by the French bishops, and to the German bishops who he judges to have acted much more consistently with the duties of their office.

DeLubac’s Main Criticisms of the French Bishops

Presuming the qualifications I just summarized, de Lubac enumerates five main criticisms of the French bishops, which I will sketch below. These include (1) a failure to understand the independence of the Church, (2) a failure to see their role as a voice for the God of justice, (3) failing to recognize and warn against the false doctrine being advanced through Nazi propaganda, (4) being associated primarily with those in power instead of with the broader population and the persecuted, and (5) becoming disconnected from the universal Church. I read these not simply as a historical inquiry, but as an occasion to consider how Catholics should properly respond to oppressive regimes in any time and place.

[An undated photo of Henri de Lubac from the Catholic Church in Lyon, France]

1. Failure to Understand the Independence of the Church from the State

De Lubac begins by explaining that these “bishops do not usually possess a very strong feeling of the independence of the Church.” He writes that although “most of them are neither politicians nor social climbers, but sincerely pious and zealous prelates, they allow themselves to be easily led by the civil authorities.” This failure of bishops to properly understand what de Lubac describes as the independence of the Church led them to think the only possibilities were to be collaborators or members of the resistance. He elaborates this first point as follows.

When [the bishops] learned that people would like them to be more independent, they thought they were being asked to be more oppositional, so difficult was it for them to imagine having a higher status (despite expressions such as the famous “loyalty without subjugation”). People only wanted them to act more like bishops.

What de Lubac means by this will be clarified by his subsequent points about, for example, speaking for the God of justice. He continues with a reference to how they undermined their spiritual authority from the beginning of the occupation.

The fact is that many of them abdicated their spiritual authority, in practical terms, from the beginning of the Vichy regime (a fact based on a number of thoughtless acts they committed) and were no longer able to regain their independence without appearing to join the opposition [emphasis added].

An example of this deficient sense of the independence of the Church was the exaggerated importance the French bishops gave to “the question of political power and of the ‘legitimacy’ of Vichy.” They failed to recognize—if I understand de Lubac correctly—that “the spiritual responsibilities of the leaders of the Church” remain intact regardless of the legitimacy of the political regime.

This failure, he says, led to “numerous acts of servility.” The examples de Lubac lists include a bishop moving “one of his priests who was guilty of having read a statement to a church group (written by cardinals and archbishops) that the [civil authority] did not like.” Other examples involved the Church being “called upon in the most brazen way to cover for a crime.” In other cases they obediently submitted “episcopal acts to state censorship,” with “many bishops censuring themselves in advance, so to speak.”

For a contrary example of what de Lubac considers virtuous behavior, he praises Monsignor Bruno de Solages, who “refused to allow a truncated doctrinal text of his to be published” (268).

This first point about the need to recognize the independent role of the Church is best understood in light of those discussed below. Regarding the contemporary relevance of de Lubac’s emphasis on the independence of the Church, it seems to me that the tendency among influential conservative Catholic intellectuals towards neo-integralism and postliberalism is profoundly misguided in threatening the independence of the Church. It foolishly encourages clergy and others to think the goal is to establish an alliance with the state so its coercive power can be used to uphold the moral order—in the areas of sexual, marital, and life ethics—whereas the common good as the Church understands it suffers unimaginable harm with the world falling into a dystopian future.

2. Failure to Be a Voice of Conscience for the God of Justice

Second, while Bishops were solicitous to protect and defend the [especially material] goods of the institutional Church like schools, they failed “to see that their role went far beyond that. They did not understand that deep down, they were called upon to …be the voice of conscience and to plead for the God of justice.” The French Jesuit writes as follows.

Hence the scandal of the past four years, so often the Church appeared satisfied, while justice was violated everywhere, consciences tortured, and Christianity itself was trampled upon. The Church of France appeared in the eyes of all to be benefitting heinously from a terrible situation.

With this history, it should be no surprise that the faith declined rapidly in France, and elsewhere in Europe where Catholic sympathy for fascism was widespread. In his discussion of Bishops failing to manifest justice, de Lubac also mentions “[f]unds given to religious schools through a somewhat humiliating process, together with the outward prestige given to certain prelates (Cardinal Gerlier’s trip to Spain, etc.).” So the Church appears to be benefitting while injustice predominates, without due comments from Bishops.

I would add that, as St. Thomas Aquinas wisely teaches, the virtue of veracity is to say the truth when and as one ought, and one looks to the example of the virtuous person to see examples of this being done when and as it ought to be.

In contrast to the failure to speak prudently for the God of justice, de Lubac praised the “much more noble” attitude of the German episcopate of whom he writes:

They never thought that the submission owed to the state could keep them from raising their voice on any topic. They never used the concordat and the material advantages they had (despite many breaches) as an excuse to turn a blind eye to so many doctrines and acts that were contrary to their faith or simply to natural moral law! [The German bishops] never believed that they could remain silent, because their faithful would not suffer directly. They did not consider themselves merely as leaders and defenders of the faith, but as witnesses in God’s realm and in that of God’s justice.

The failure of the French bishops to speak for the God of justice left “[t]oo many Catholics … to believe that religious affairs are going well, when they themselves are not troubled, when their side is triumphant.” This remark should raise the question of what percentage of American Catholics have been left to believe that religious affairs in the United States have been going well because “our side is supposedly winning”?

De Lebuc writes that instead of reminding the people “of the spirit of the Gospel, the attitude of the French episcopate only served to ground them in the sensual realm.” In my opinion, those influential Catholics—no matter how famous, eloquent, well-funded, or highly placed—who have given the impression that the proper response to the contemporary moment is to “oppose wokeness” need to make a deep examination of conscience and bear the fruits of repentance. De Lubac’s contrast between the spirit of the Gospel and the sensual realm is reminiscent of the thought of St. Paul who called upon his flock to live not merely according to “the flesh,” but according to “the spirit,” who strengthens us to participate in the pattern of Christ’s redeeming love. For de Lubac, such remarks seem to reflect his rejection of the two-tier schema of the natural and supernatural orders. He blames this failure of episcopal leadership for the fact that “in the majority of “Catholic” settings [in France] and even in a number of convents, the Church seemed deaf to even the most compelling and urgent calls for charity” (269).

As I read it, this second point on justice also helps to explain the first on independence. It emphasizes the need to be a witness for Gospel justice, for the inbreaking kingdom, and for charity in the face of affronts to human dignity. According to sound moral theology, the virtuous way to speak out for justice in a given circumstance is the fruit of a virtuous character. This means it will follow from a character formed by love of the virtuous goods at stake, not from a disordered affection for wealth, prestige, or comfort. Love of the virtuous goods like justice, fraternal love, and solidarity is essential to giving the Gospel witness of Christian holiness. A “fleshly” attempt to coerce our neighbors through entanglements with the state is contrary to the life of Christian holiness and is a counter witness to the Gospel.

Regarding the contemporary relevance of bearing witness to the God of justice, therefore, I think the Church in the United States is falling far short. As the offenses against justice have perhaps never been more plentiful, the Catholic voices speaking about them are limited primarily to a series of media outlets that support Catholic Social Teaching such as Commonweal, America, and the National Catholic Reporter. At a time when the country has recently witnessed some of the largest protests in American history over—for example—the deconstruction of our public institutions, the Catholic presence so far has been difficult to detect.

3. Bad Doctrine Corrupted by Fascist Propaganda

Third, de Lubac writes that “the entire body of the Church was suffering from serious failings from a doctrinal perspective.” On the one hand, episcopal letters had manifest “shortcomings” in how they dealt with the situation at hand. At the same time, “Hitlerian propaganda unleashed an enormous number of works, journals, newspapers, brochures, publications, and lectures of all kinds on our country.” The French Jesuit continues as follows.

Much of this propaganda, often in direct opposition to the faith, Catholics; part of it was directed towards them, and it was not unusual for it to be forced upon them. Sometimes it came from Catholics, priests even (I will cite, as an example the brochure of Fr. Gorce, published in 1941, In Order to Make the Best of Defeat) in a watered down form.

Such propaganda, de Lubac writes, was never singled out for criticism by bishops, nor did they even warn against it. It seems possible, therefore, that most bishops were not even aware of the existence of such propaganda, nor did they rightly recognize it “as heinous,” but tended to “attribute little importance” to it. He writes that the “negative consequences” of failing to recognize and address this propaganda “were considerable. They contaminated many segments of the population, especially young people.” He writes that the threat posed by this propaganda was so poorly understood that “[t]here was no problem with sending Catholics, even priests, to be indoctrinated” into Nazi propaganda.

With families divided by toxic and propagandistic media over especially the last decade, has the Catholic Church spoken out about it? Is there even a way to fruitfully do so?

De Lubac recalls the example of when a revered theologian, on the other hand, “wrote a perfectly cautious and balanced deliberation on obligations in relation to the occupier and the Vichy government.” The “bishops treated [his analysis] as if it were the ridiculous rough draft of a school child.” They instead took “their inspiration from the columns of Action française.” This fascist-adjacent movement founded by the atheist but pro-Catholic monarchist Charles Maurras had been condemned by Pope Pius XI in 1926. As I wrote before, de Lubac’s philosophical mentor Maurice Blondel had written a devastating critique of the integralist mentality of such Catholics, so the French Jesuit was well-prepared to understand the issues at stake.

Even worse, according to de Lubac, “the majority of bishops…adopted an attitude…that condemned Christians who were in the Resistance, even if they did not take part in any violence, even if they were not involved in political opposition.” Perhaps they were reading the prominent speculative Thomist Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange, OP5 who was outspoken in his support of Vichy, and had even argued that support for the Free-French Resistance under General De Gaulle was “a mortal sin,” as I noted in a previous post on Yves Simon’ book The Road to Vichy. Against their reliance upon what de Lubac calls the “derivative idea” of legitimacy, a proper understanding of legitimate authority depended on what he describes as the “basic notion” of the common good.

De Lubac also pointed to the failure of the bishops to warn against the “especially ridiculous” cult of Marshal Philippe Pétain, which associated them with “ceremonies, comments, and sacrilegious writings,” which they allowed without calling for Catholics to instead maintain their “Christian dignity.”

On the contrary, the disequilibrium had penetrated into the sanctuary. Did not certain bishops swoon in admiration when they spoke of the Marshal saying that he was inspired? Another, did he not say that he had to keep himself from falling to his knees and asking for [Pétain’s] benediction? Yet another, did he not effusively share the emotion he had felt when the Marshal told him: “They call the Virgin the queen of the martyrs, am I not the king of the martyrs?” Statements of this kind were countless. And did we not see a stained glass window installed representing the Marshal, in a well-known sanctuary, given by a member of his cabinet?

De Lubac sees doctrinal corruption, beginning with a distorted understanding of the Church in relation to the state and worsened by Nazi propaganda, as the reason “why the Church of France, overall, was silent when faced with the Nazi peril.” Even if they were under “terrible oppression,” the “bishops were the only ones who could have spoken, had they wanted to.” Their widespread failure to do so “had incalculable consequences.” These included leaving “their clergy exposed, defenseless to all the forces of propaganda and pressure that were foisted upon them.” This propaganda was present in “almost all Catholic newspapers” which “…were not only conformist, but ‘collaborationist.’” Because of the silence of bishops, “good and worthy priests, in more than one region, ended up declaring the wish that Hitler win and complaining about the resistance—sometimes, alas, they did even worse.”

Like the situation in Vichy France about which de Lubac wrote, it would seem that we have in the contemporary United States the bad doctrine of neo-integralist postliberalism that entangles Church and state. We also have a vast network of conservative intellectuals, think tanks, and media outlets propagating messages that keep Catholics in the dark about the situation we face.6 This situation of polycrisis includes the deconstruction of the public institutions that are integral to the common good, the weaponization of public institutions, and the deconstruction of the postwar international order, to say nothing of the climate crisis. If de Lubac’s assessment is on the mark, bishops will need to speak out about, and exemplify, bearing witness against violations of human dignity and justice. For them to do so, however, they will need the support of Catholic intellectuals, and a supportive media ecosystem and grassroots infrastructure.

4. Church Leadership Disconnected from the Life of the People

Fourth, de Lubac charges that Church leadership was too often disconnected from the life of the people because of their acquaintances, their ecclesiastical customs, their prejudices and their routines. They were too often “guided by power, by the opinions of those in official positions or small groups, rather than the broad currents of national conscience.” In this way, the bishops tended to align with the collaborators of Vichy whereas the great masses of the nation at least sympathized with the resistance against the Nazi occupation.

In our day, wealthy and powerful laity have much greater influence in the Church, including through organizations that seek to shape the Church, and the society through political activity. In my opinion, this presents a major challenge to the contemporary Church as such groups seem inclined toward supporting an oligarchy that is destroying the institutions that Catholic Social Doctrine thinks are integral to the common good. In the best case, the socially-oriented pontificate of Leo XIV offers an opportunity to help such organizations and individuals to foster a properly Catholic identity and mission.

De Lubac illustrates this disordered inclination toward the powerful with examples of an archbishop who presides over events with collaborators, and participates in their feasts. He also forbids listening to English radio broadcasts that were transmitting Allied propaganda, declaring that it was sinful. The news reels that were played in the Vichy cinemas, moreover, frequently included shots of cardinals, to signal that the Church supported the fascist regime, thereby discrediting the Church in the eyes of most citizens. If the communist youth in the resistance looked forward to hanging such clergy when the political winds changed, the Catholic youth wanted at least to keep their distance from such collaborationist clergy to avoid sharing in such a fate.

De Lubac concludes this fourth point with the observation that the bishops could not have acted as they often did if they identified with the suffering of the people instead of with the elite, who were typically collaborators. Such experience illustrates the emphasis of Pope Francis on pastors having the smell of the sheep, as exemplified by the photos of then Cardinal Robert Prevost wading through the flood waters to serve his people.

5. National Bishops Cut off From Communion With the Universal Church

Fifth, de Lubac says the French bishops adopted “a weakening of their belief in the universality of the Church and the unity of the episcopate. There was a renewal of interest in Gallicanism.” They ignored papal encyclicals like Mit brennender Sorge (1937) that warned them of the evils of Nazism, and did not even mention that it was omitted from a published volume of the documents of Pius XI, dismissing it as a political matter between the Vatican and the Third Reich.

Another bishop forbade a small newsletter called The Voice of the Vatican, which provided without additional commentary and with every possible attention to exactitude, the messages of Vatican Radio. Others had no difficulty sacrificing the very principle of Christian unionism, despite the formal and relentless directives from the Holy See on this subject, saying that they were outdated.

Although there had been a troubling antagonism of many conservative Catholics toward Pope Francis in recent years, I have been delighted to see that most venues have been much more favorable towards Pope Leo XIV. Whether they can better receive the authentic social doctrine of the Church that he seeks to advance will be an important test of our communion with the Holy See.

Conclusion

Henri de Lubac’s 1944 memorandum has—in my opinion—a surprising degree of relevance for Catholic leaders in the United States as we have been undergoing a rapid transition to authoritarianism. The current administration came into office, moreover, with the support of about 56% of Catholic voters and 60% of white Catholic voters. Much like the coalition of conservative and anti-democratic forces that contributed to the collapse of the German Weimar Republic, Catholic conservatives and anti-democratic forces were an important part of the coalition that seems to have toppled the American Democracy that was the lynchpin of the postwar international order.

At a time when prominent Catholics are trying to implement a postliberal order that they claim is inspired by Catholicism, de Lubac’s analysis suggests that Catholic leaders will need to recognize the proper independence of the Church. They will also need to fulfill their duty to bear witness to the God of justice, at a time when grave injustices are multiplying at a dizzying pace. As our new Holy Father calls for a renewal of Catholic Social Doctrine, American Catholic leaders will need to recognize and confront the distorted messages that are being propagated by some of the most influential American Catholics. As Pope Francis has pleaded and Pope Leo XIV has exemplified, American Catholic leaders—both clerical and lay—will need to learn to reconfigure alliances favoring the powerful and associate with the marginalized. After a pontificate marked by an unprecedented degree of tension between the Holy See and key institutions of the American Church, we will need to rebuild the bonds of unity, affection, and Catholic doctrine—especially social doctrine—between the Church in the United States, the Holy See, and the universal Church.

Under the leadership of Pope Leo XIV and with the help of the Holy Spirit, we should not underestimate the prospects for doing so, and for God doing so much more than we can ask or imagine (Eph 3:20).

This introductory section draws upon https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henri_de_Lubac.

Catholicisme: les aspects sociaux du dogme (Paris: Editions du Cerf, 1938).

This work was published in the United States, however, as Catholicism: Christ and Common Destiny of Man, the subtitle of which focuses more narrowly on the eschatological destiny of humanity whereas the French original carries broader connotations through de Lubac’s reference to dogma. This narrowing is unfortunate for those of us in the United States, however, where the contrary ideology of individualism flourishes, thanks to the largesse of libertarian donor networks, who have shaped the culture.

Journal of Jesuit Studies 5 (2018) 266-277.

Although I consider myself a Thomist, and even taught a seminary elective on Garrigou-Lagrange’s spiritual theology, I think his support for fascism should be taken as a warning for his admirers. From it they should recognize how an emphasis on speculative thought can combine with a deficient account of practical reason to render the discernment of the magisterium regarding Catholic Social Doctrine unintelligible.

I could say something similar about the illiberal left, but I don’t think the situation is remotely analogous.