In this post, I will introduce an underappreciated dimension of the fall of Germany’s Weimar Republic (1918-33) that suggests significant parallels to developments in the United States. Many are aware that the Weimar Republic—which was established in the wake of the First World War—was burdened by the Treaty of Versailles, which included punitive war reparations. Many are also aware of the hyperinflation that plagued Weimar, especially during 1922-23. Indeed, Weimar struggled throughout its existence with a wide range of challenges. Opponents of democracy even pointed to the struggles and weaknesses of Weimar to blame it for the rise of Nazism and the horrors it unleashed.

[Wikipedia. Crowds in Berlin under the imperial war ensign during the Kapp Putsch]

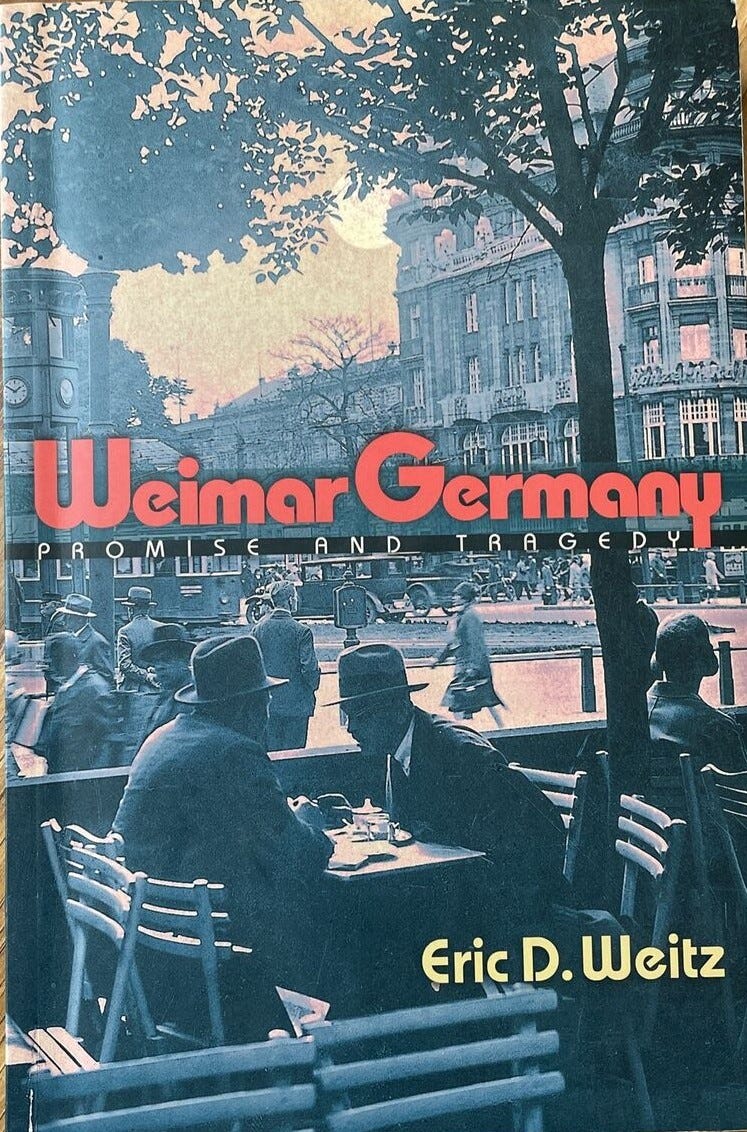

An acclaimed work by Eric D. Weitz entitled Weimar Germany: Promise and Tragedy is especially valuable in presenting other essential aspects of the story of Weimar, including how it was stabilizing by 1925, and the way it fostered creativity and freedom. Weitz also gives considerable attention to how it was continually undermined—and ultimately destroyed—by a coalition of conservative and antidemocratic forces that included business persons, members of public institutions, the judiciary, the media, and the military, along with religious leaders. The most extreme of these right-wing forces was the Nazi party led by Adolf Hitler, who was put into power—not by popular vote—but by an agreement with the other conservatives, who foolishly thought they could control an aspiring dictator.

Weitz’s emphasis on how these conservative and antidemocratic forces in Weimar Germany were decisive in giving us the Third Reich complements the story I have discussed in previous posts regarding how Catholic Social Doctrine evolved through the experience of the interwar years. Although social Catholics following the example of the 19th Century Bishop Ketteler in Germany, Maurice Blondel in France, Luigi Sturzo and others in Italy, and Msgr. John A. Ryan in the United States were early advocates of participation in the democratic political process, they often represented a minority position. All too common was a radical anti-modernism, antiliberalism, and anti-communism that aligned many Catholics with authoritarian, proto-fascist, and fascist forces. Such illiberal stances were especially common among the leading Catholic scholastic theologians like Cardinal Louis Billot, SJ, Pierre Descoqs, SJ, and Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange, OP, and by the many Catholics downstream of their influence.

Through the tragic experience with totalitarianism, the postwar Church embraced the integral and solidary Christian humanism that characterizes contemporary Catholic Social Doctrine. As I discussed in a previous post, this evolution is traced brilliantly by James Chappel in his Catholic Modern: The Challenge of Totalitarianism and the Remaking of the Church. This evolution resulted in a significant consensus among postwar Catholics and Christians that the culture of human rights and constitutional democracy were self-evidently required by contemporary Christianity.

Weitz on the Coalition that Destroyed Weimar and Gave us the Third Reich

To keep this post from getting out of control, I will just include some of Weitz’s concluding remarks, which summarize what he demonstrates at length in his chapters, especially chapter 9 on “Revolution and Counterrevolution on the Right.” He concludes:

Weimar did not just collapse; it was killed off. It was deliberately killed off by Germany’s antidemocratic, antisocialist, anti-semitic right wing, which, in the end, jumped into political bed with the Nazis, the most fervent, virulent, and successful opposition force. Weimar may indeed have had too few democrats, too few people willing to stand up and defend the republic (404).

Weitz proceeds to note a phenomenon that we have also seen in the United States, namely that “[t]he radical Left certainly did not help matters.” For example, Weimar fostered a libertine sexual ethic that alienated religious and cultural conservatives, thereby weakening support for democracy and providing an opportunity for the radical right. He also notes that the right had “major resources. It had intellectual capital in the form of well-placed professionals and cultural figures who spoke and wrote in the same language as the Nazis” (404). This echoes an analogous situation in the United States especially since the 1971 Powell Memorandum and the “master plan” which resulted in the investment of massive resources by conservative / libertarian business interests to weaken public institutions thereby enabling the oligarchic takeover that is now obvious.

The right had spiritual capital in the many pastors and priests who thought Nazism was at least acceptable. The right occupied government offices and military commands and controlled great segments of the industrial and financial resources of the country. To be sure, not every businessman or pastor was pro-Nazi, and among those who engineered the final destruction Hitler was more tolerated than loved. But the collective hostility of those who commanded Germany’s resources, staffed its major institutions, and found a democratic, socially minded, and culturally modern and innovative society intolerable—those are the people who destroyed the republic and without whom the Nazis would never have come to power. Their attacks on Weimar, coupled with the Nazis’ formidable political instincts, undermined the system. In their wake came the large, varied German middle classes and many from the lower classes as well, who found disorder deeply disturbing and understandably so (405).

I will leave it to those with “eyes to see and ears to hear” (Mt 13:16-17) to recognize the details of which parallels should be drawn between the Weimar Republic and the United States. These would include—on the one hand—those in the United States who have “at least accepted” an increasingly radicalized right, while often railing against American liberal democracy. More specifically, these would include presumably well-meaning—but insufficiently informed—members of the clergy, academics, public servants, business persons, or financers who did not understand the “master plan” to overthrow our pubic institutions, the health of which determines whether we are on the path to a failed state or to a flourishing society. Weitz offers a sobering observation for which we can also envision parallels: “[i]n the ensuing years, the members of the right-wing elite and many other people realized that they had gotten far more than they had bargained for in 1932 and 1933. Their Nazi partners were not to be controlled. But that was the bed that they had made for themselves” (405).

Conclusion

Compared to other literature on Weimar Germany, Eric Weitz emphasizes—on the one hand—the impressive accomplishments and immense promise offered by Weimar Germany. On the other hand, he helpfully marshals evidence that the blame for its tragic fall to the Nazis under Adolf Hitler lies decisively with a coalition of conservative and antidemocratic forces. Although the role of Catholics is not a major theme for Weitz, his narrative discusses how many German Catholics were part of this former coalition, while also recognizing that many others worked to realize the potential of the Weimar Republic, consistent with the emerging social tradition of the Church. Although the libertine sexual ethic that permeated Weimar society was a major point of contention with the Church and lessened the support of Catholics for the republic, Church leaders also spoke out clearly and frequently against the evils of Nazi ideology and policy. For this reason the Nazis saw the Church as a dangerous opponent and sent thousands of Catholic priests, religious and laity to their deaths in the concentration camps.

Without question, the diverse roles of Catholics in both the Weimar Republic and Third Reich can offer a valuable source of reflection for contemporary American Catholics, discerning how we might contribute to the common good in what remains of Weimar America.