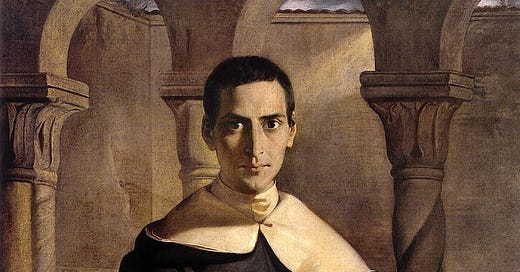

Remembering, Identity and Henri-Dominique Lacordaire, OP (1802-61)

Early Dominican Advocate for the Separation between Church and State

[Image from Wikipedia ]

Reminder: readers can view the following post, and dozens of other ones, at the Social Catholicism and a Better Kind of Politics website.

I had the occasion in recent days to think about the example of Jean-Baptiste Henri-Dominique Lacordaire, OP (1802-1861), who is remembered especially for reestablishing the Dominican Order in post-revolutionary France. I was reminded of Fr. Lacordaire while relistening to the Audible version of Helena Rosenblatt’s timely and important work, The Lost History of Liberalism: From Ancient Rome to the Twenty-First Century. Rosenblatt briefly discusses this visionary Dominican’s early—but futile—efforts to have the Church recognize the compatibility between Catholicism and liberal principles like the separation of Church and state.

The Church would finally recover the original Christian understanding that Jesus’s kingdom was “not of this world” after the Second World War. Through the Second Vatican Council and through the development of Catholic Social Doctrine since that era, the Church has advocated what the 2004 Compendium of the Social Doctrine of the Church presents as an integral and solidary Christian humanism. This way of living fraternal charity in the world includes friendly dialogue with all branches of knowledge, accepting contemporary representative and constitutional forms of the political community, and working to build societies marked by social friendship.

This participative, incarnational and dialogical relationship with the modern world of secular states has been increasingly challenged since the Second Vatican Council. This began in the early 1970s with the one-time Vichy-supporting and future schismatic Archbishop Marcel Lefebvre and his followers. The challenge to the common interpretation of the Council’s Dignitatis humanae: Declaration on Religious Liberty became more widespread in recent decades through the advocacy of radically antiliberal and postliberal perspectives by influential American Catholics.

In our historical context in which Catholic postliberalism is a key pillar of the American hard right, the prescient Lacordaire was fresh on my mind as I arrived at my alma mater, the Dominican House of Studies (DHS) in Washington, DC for the Annual Meeting of the Academy of Catholic Theology. Upon entering the building, I was reminded of Lacordaire by a photo of the dozens of men in formation to this East Coast province of the Dominicans.

[An unlabeled photo of Dominicans from https://opeast.org/vocations/]

Given the way my own work has evolved from its beginnings in New Testament studies and Thomistic virtue ethics to focus on Catholic social teaching, I have reason to hope that many of these young Dominicans might become a locus for the renewal of Catholic Social Doctrine in support of the emphasis of our new Holy Father, Pope Leo XIV. From my own experience, I knew it was possible to go from an extreme of largely ignoring and underestimating Catholic social teaching—as I did until I was several years beyond the completion of my doctoral studies—to becoming a convinced advocate of it. One of my regular prayers, moreover, is to ask God “to do far more abundantly” than I can “ask or think” (Eph 3:20), so I will apply that to my fellow disciples of St. Thomas and hope for a new flowering of social Catholicism.

These East Coast Dominicans, of course, already have men who do important work in support of Catholic Social Doctrine. On the faculty at Providence College, for example, these include the economist Fr. Albino Barrera, and the lawyer Fr. Thomas More Garrett, who serves as Promoter of Catholic Social Teaching for the province. Given the vibrancy of the province, however, and the signs of the times, I think there is immense potential for Dominicans and those they reach to become part of a robust renewal of Catholic social teaching.

The first keynote of the conference offered a framework that I think could help a range of Catholics come to a deeper understanding of our social tradition and thus come to identify strongly with it.

A Keynote Address on Memory and Identity

On the first evening of the ACT, we heard an artfully crafted keynote address by the patristic scholar Ellen Scully on “Preserving the Memory of the Creed for the Identity of the Church” (emphasis added). To paraphrase, Professor Scully argued for the importance of studying the details of our doctrinal tradition, such as the debates surrounding the formation of the creed. Detailed knowledge of such debates is normally of primary interest to a limited range of specialists, who nevertheless provide an important service to the Church in keeping those memories available. At certain times in the life of the Church, however, the broader community of believers needs to be reminded of these historical details, such as when alternative views threaten the authentic tradition.

In such times, a retrieval of the tradition can serve as a way to “refresh the memories” of the wider Church. On the one hand, this helps us to identify with the truths of the faith. On the other hand, this can help us to reject the views that our forefathers came to see as contrary to the truth of the Gospel.

At a time when the last two popes have described the current geopolitical situation as a polycrisis, when an authoritarian and dystopian future threatens the human family, and when our new Holy Father is calling for a renewal of Catholic social teaching, I think ours is an age when it is important to understand how the magisterium came to articulate contemporary Catholic Social Doctrine, and what it put aside in so doing.

Remembering the Development of Modern Catholic Social Doctrine

In this substack, and in the historical parts of the related edited volumes, I have begun—with the help of collaborators—to illustrate how the Church came to articulate this social doctrine. The Church’s gradual articulation of contemporary Catholic Social Doctrine is the flipside of how we broke from the old preference for an alliance between throne and altar, through which the Church could employ the coercive power of the state to enforce aspects of the moral order. This understanding had long roots in the Church’s role in preserving civilization, when populations were largely uneducated, and when a more paternalistic orientation toward society made more sense.

The need to break from this paternalistic stance follows from the complexity of modern states, and the greater literacy of populations, among other factors. It also implies the need to learn to live as disciples of Christ by participating in efforts to advance the common good within the forms of representative government that were emerging in the modern era alongside the creative destruction caused by the unfolding of market economies. Such participation entailed adopting a more fraternal stance. Instead of the emphasis on imposing moral order that accompanies the paternalistic stance, Catholics should prefer the fraternal one for multiple reasons. These include respecting the dignity of every person created in the image of God, living all the virtues as perfected in charity, understanding charity as a kind of friendship, and adopting a “synodal” way of walking together with Jesus on the path of discipleship.

Pope Leo XIV makes a similar point regarding Catholic Social Doctrine when he says:

“Indoctrination” is immoral. It stifles critical judgement and undermines the sacred freedom of respect for conscience, even if erroneous.

In breaking from the paternalism of the integralist ideology that had justified interwar alliances with fascist states, the Catholic Church after the Second World War came to rediscover something closer to the original Christian position in which Christ’s “kingdom is not of this world” (Jn 18:36). We advance the realm where God’s rule is present, moreover, not through forming political alliances that help us to impose a moral order upon our fellow citizens. Such an imposed moral order, in my opinion, would be a profoundly distorted one that is directly contrary to a fundamental principle of justice like the golden rule, and the friendship of charity.

We actually advance the realm where God’s rule is present—on the contrary—by exemplifying the Christian virtues, such as by working in solidarity for the common good, and through dialogue and persuasion.

In future posts, I will continue to flesh out the historical narrative by drawing upon Rosenblatt’s Lost History of Liberalism to discuss the earliest Catholics who advocated that the Church should accept what were just coming to be called liberal states in the decades after the French Revolution. In the following excursus, I will recap the narrative I have been sketching in this substack. In the subsection following it, I will briefly treat Lacordaire and some of his collaborators, who presciently but unsuccessfully advocated for a Catholic embrace of the liberal separation of Church and state.

Excursus on the Emergence of a Fraternal Socio-Political Orientation:

For new readers, let me recall that—in previous posts—I have introduced various figures who helped the Church discard an integralist model of aligning with state power to paternalistically impose moral order. Instead, we came to embrace a model of fraternal collaboration in free societies for the common good, which is central to contemporary Catholic social doctrine. These figures have included Fr. Félix Varela (1788–1853), a Cuban-American contemporary of these French Catholics,1 and Wilhelm E. von Ketteler (1811-1877), who is widely considered the father of modern Catholic social teaching. In upcoming posts, I will discuss the social Catholic study circles he inspired, such as the Fribourg Union, which influenced the first modern social encyclical, Leo XIII’s 1891 Rerum novarum: On Capital and Labor. The American experience also seems to have influenced Leo XIII, as Cardinal Gibbons of Baltimore personally delivered a powerful letter to Leo in support of the Knights of Labor union, and urged him to write on the topic. For their broad fraternal collaboration in the political process for the common good, I have discussed how the French social Catholics inspired by Rerum novarum were attacked by supporters of Action Française under the leadership of the proto-fascist atheist Charles Maurras. They were defended, however, by the great ressourcement philosopher Maurice Blondel (1861-1949), whose rejection of integralism was reiterated by Hans Urs von Balthasar and influenced the ressourcement tradition, at least until more recently. I have also discussed how, in early twentieth century Italy, social Catholics struggled to respond to the industrial revolution in fidelity to Rerum novarum. This ultimately led to postwar Christian democracy of which Fr. Luigi Sturzo (1871-1959) was considered the father. After the war, social Catholics like the venerable Robert Schuman of France, Germany’s Conrad Adenauer, and Italy’s Alcide de Gaspari became the Catholic founders of postwar Europe. These social Catholics were often opposed by the great neo-scholastic speculative thinkers like Louis Billot, SJ (1846-1931), Pedro Descoqs, SJ (1877-1946), and Reginald Garrigou-Lagrange, OP (1877-1964).2 The predominantly speculative but deficiently practical perspective of such scholars inclined them toward alliances with fascists to help them impose moral order, as Yves Simon discusses in his account of The Road to Vichy. In the United States, leading social Catholics like Msgr. John A. Ryan and Fr. Ted Hesburgh, CSC brought Catholics into fruitful alliances to foster the common good. For Pope Francis, his last social encyclical Fratelli tutti: on Fraternity and Social Friendship, wisely emphasized the fundamental point that Catholic Social Doctrine is about a fraternal way of loving our neighbors in the modern world.

I now turn to Lacordaire and his early effort to help the Church recognize how it would benefit from embracing some of the key elements of modern secular states.

Remembering Lacordaire, Early Dominican Champion of the Separation of Church and State

For the many of us close to the Dominican tradition, a review of Lacordaire’s efforts to reconcile the Church with “liberalism” can be part of a “remembering” that enables us to identify more closely with the authentic social doctrine of the Church. More importantly, it can therefore help us to live this teaching, and thereby incarnate the divine love in the world.

In Rosenblatt’s Lost History of Liberalism, Lacordaire is briefly discussed in a chapter that treats the mid nineteenth century French “liberal Catholics” who defended the compatibility between an understanding of “liberalism” together with—perhaps surprisingly—an ultramontanist form of Catholicism. The most important of these Catholics were Fr. Hugues Felicité Robert de Lamennais, the Viscount Charles de Montalembert, and Fr. Jean-Baptiste Henri-Dominique Lacordaire, whose advocacy for liberalism predates his joining the Dominicans and re-establishing the Order in France, although he continued to consider it best for the Church.

The wikipedia article on Lacordaire adds additional details, so I will draw primarily from that in the following paragraphs. By advocating a reconciliation between the Church and an early form of political liberalism, the main desiderata that these men sought were reflected in their motto “Dieu et la Liberté!,” that is, bringing together “God and Freedom”! A statement of demands from the December 7, 1830 issue of L’Avenir spells out their agenda in greater detail. It specifies a freedom of conscience, understood at least primarily as freedom of religion, and a corresponding separation of Church and state, including discontinuance of state salaries for clergy. More broadly, they sought freedom of the press, freedom of assembly, and the expansion of suffrage (voting). Although one might agree with the goal of freeing the Church from its entanglement with the French state, it is no surprise that the proposal to abandon income and political power will raise opposition.

Convinced they had a great proposal for the Pope, these three men confidently traveled to Rome to make their case to Gregory XVI. They quickly became disenchanted, however, by the way he received them. Lacordaire promptly distanced himself from the other two, who were not inclined to accept the negative response that the cold reception suggested would be forthcoming. Gregory responded officially on August 15, 1832 with the encyclical Mirari vos that condemned freedom of conscience and freedom of the press. Lamennais responded by renouncing his priesthood and wrote a work condemning the contemporary social order, which provoked the 1834 encyclical Singulari Nos. These developments delayed significant Vatican efforts to reconcile the Church with the modern world until perhaps Leo XIII’s 1891 Rerum novarum: On Capital and Labor.

The 32-year-old Lacordaire, just 5 years from ordination, went out of his way to submit to the Pope’s judgment, writing a letter to that effect, and likening Lamennais’ behavior to that befitting Protestants. Between 1834 and 1836, Lacordaire distinguished himself through lectures and preaching. He returned to Rome in 1836 for further studies with the Jesuits, reaffirming his ultramontanism, which aroused the ire of the Archbishop of Paris, who was a Gallican which meant he sought independence from Rome on temporal matters. Lacordaire decided to enter the Dominican Order in 1837 and began in 1838 to identify novices for a French province, before formally joining the Order in 1839.

After his humble submission to the magisterium regarding religious freedom, Lacordaire perhaps surprisingly supported the liberal revolutions of 1848 in the Italian states, and even the French invasion of the Papal States, which was bound to invoke Papal ire. He was deeply convinced, however, that the Catholic entanglement with states was obsolete and harmful. The French Dominican province was re-established in 1850 and Lacordaire was elected by his confreres as superior and reelected by them in 1858. Pius IX, however, appointed his philosophical opponent—a Dominican named Alexandre Jandel—to be the vicar general, and then the Master of the Order, apparently as a check on Lacordaire.

From the perspective of the Second Vatican Council and Dignitatis Humanae: Declaration on Religious Liberty, Lacordaire was right, but about 135 years ahead of the Church. If he, and the discernment of an ecumenical council under the leadership of the Pope were right to declare a right to freedom from coercion in matters of religion, then perhaps our remembering of Lacordaire can be helpful in shaping our identity as Catholics. More specifically, perhaps it can even help us to identify with a long tradition of social Catholics who exemplify a fraternal participation in the political process, and against those who seek paternalistic collaboration with autocrats in departure from the long discernment of the magisterium.

Varela was similarly early in recognizing not just the separation of Church and state, but also the value of constitutional and representative government, the theory of which he knew well. Varela was also among the most erudite men of his day, and advocated for justice and human dignity out of the Catholic and Thomistic tradition.

Other than his integralism, I think Garrigou was an important thinker worthy of study. I even offered an elective on his spiritual theology when I taught in seminary.